Mantis Boxer Meets A Karateka - A Chat with Iain Abernethy

I have a great first-time conversation for all of you today. I’m joined by Iain Abernethy, a karateka from the UK. Iain runs a popular YouTube channel known as PracticalKataBunkai, is the author of multiple books, and DVD’s, and travels the world teaching Karate.

Over the past year or two…

I have a great first-time conversation for all of you today. I’m joined by Iain Abernethy, a karateka from the UK. Iain runs a popular YouTube channel known as PracticalKataBunkai, is the author of multiple books, and DVD’s, and travels the world teaching Karate.

Over the past year or two, many of you have reached out to me urging Iain and I to connect due to our similar approaches to the martial arts. Well it finally happened, and we have you to thank for this exceptional conversation. Thank you and enjoy.

If you haven't already - I highly recommend you follow Iain @ -

Website - https://iainabernethy.co.uk/

YouTube - https://www.youtube.com/user/practicalkatabunkai

Instagram - https://www.instagram.com/iainabernethy/

Ezekiel Choke to Americana Lock (Keylock)

Here is another attack using the same sneaky Americana I've been using from under the head. In this example, we go from the Ezekiel Choke and our opponent defends it. Because my weight is side shifted, my savvy friend will feel my opposite leg go light, and try to push my knee into half guard to gain a better position.

Rather than stay there and let them get half guard, we skip over to position 2 of Side Control. Now they defend the position by trying to build a frame. This presents the arm in a vulnerable position to grab it from...

Here is another attack using the same sneaky Americana I've been using from under the head. In this example, we go from the Ezekiel Choke and our opponent defends it. Because my weight is side shifted, my savvy friend will feel my opposite leg go light, and try to push my knee into half guard to gain a better position.

Rather than stay there and let them get half guard, we skip over to position 2 of Side Control. Now they defend the position by trying to build a frame. This presents the arm in a vulnerable position to grab it from under the neck.

In order to finish them, we need to change our position however. Here is where the hip break comes into play. We hip break over to the opposite side and go to position 3 of Side Control. This gives us the position we need to finish the Keylock/Americana.

Max asked, "what happens if they block our hip break?" Great question. By attempting the hip break, it lifts their arm off the ground, so we can simply return to position 2, and throw our arm under so we can finish the Keylock/Americana from there.

--

Like the video? Hit subscribe and Get Hooked!

Stop Your Opponents Crushing Side Control

Do you hate being crushed in your opponent's side control? Here's something I've been working on in my game that will hopefully help your game. Building a mountain under your opponents crushing side control can give you space and mobility for countering their attacks, and possibly bringing us to a better position.

Do you hate being crushed in your opponent's side control? Here's something I've been working on in my game that will hopefully help your game. Building a mountain under your opponents crushing side control can give you space and mobility for countering their attacks, and possibly bringing us to a better position.

The Straight Punch - Throwing the Forward and Reverse Punch

The Straight Punch - devastating and destructive! Forward and Reverse punch are a good place to start when learning to punch in Mantis Boxing, or other striking arts. They are destructive, and can easily be modified to open hand strikes if necessary.

The following video shows the in's and out's of...

The Straight Punch - devastating and destructive! Forward and Reverse punch are a good place to start when learning to punch in Mantis Boxing, or other striking arts. They are destructive, and can easily be modified to open hand strikes if necessary.

The following video shows the in's and out's of starting to punch with these two strikes and some of the pitfalls to watch out for.

Using footwork with punches, increases the power, improves range, and helps keep us mobile instead of fixed. Check out pad drills, and blocking drills, or use these on a heavy bag to train on your own.

How to Throw a Punch...Safely

Having an improper structure, leaving a finger misplaced, or snapping our elbow, can all cause lasting damage, injuring ourselves more than the object we are trying to hit.

Whether we are hitting bags, pads, mitts, makiwara boards, or sparring partners, it's important to keep these tips in mind to keep us punching without injury for years to come.

Having an improper structure, leaving a finger misplaced, or snapping our elbow, can all cause lasting damage, injuring ourselves more than the object we are trying to hit.

Whether we are hitting bags, pads, mitts, makiwara boards, or sparring partners, it's important to keep these tips in mind to keep us punching without injury for years to come.

How to Drill Your Basic Footwork Skills

Basic Footwork is pivotal in understanding how to move when fighting/sparring. Bad footwork creates vulnerabilities in our game that our opponent can capitalize on. Once we have an understanding of our basic footwork skills, Mirror Drill becomes a great tool to help train fluidity and responsiveness, as well as range sensitivity, and neutral position; where our guard/blocks work best.

Basic Footwork is pivotal in understanding how to move when fighting/sparring. Bad footwork creates vulnerabilities in our game that our opponent can capitalize on. Once we have an understanding of our basic footwork skills, Mirror Drill becomes a great tool to help train fluidity and responsiveness, as well as range sensitivity, and neutral position; where our guard/blocks work best.

We are using some newer students to help show this drill - Lauren and Natalie, as it's important to understand that, once you have this down, you dump it and move on to the Advanced Footwork found here - https://youtu.be/UDpnleVQO60

A mantis boxing coach shared this drill with me back in 2006, and it's an excellent way to master basic footwork before going to advanced.

You can view our Basic Footwork video for more on the individual components - Shuffle Forward, Shuffle Back, Circle Left, Circle Right, Step Forward, Step Back, Change Step, and practicing them on your own.

--

Like the video? Hit subscribe and Get Hooked!

►SUBSCRIBE on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/mantisboxers

Hooking Legs

The Leg Hook is a great easy to use takedown, but sometimes our opponent steps out on us on our first attempt. Here, Thomas helps demonstrate how we use a combination of Mantis principles (strike, hook, pluck, hang, lean) to execute our initial outside leg hook attempt, and then a follow-up inside leg hook if they step out.

Afterwards we tackle the ground component and what happens if they immediately try to pull guard.

The Leg Hook is a great easy to use takedown, but sometimes our opponent steps out on us on our first attempt. Here, Thomas helps demonstrate how we use a combination of Mantis principles (strike, hook, pluck, hang, lean) to execute our initial outside leg hook attempt, and then a follow-up inside leg hook if they step out.

Afterwards we tackle the ground component and what happens if they immediately try to pull guard.

Thanks for watching.

--

Like the video? Hit subscribe and Get Hooked!

I'm Not Ready For That.

Another article on the inner demons that get in the way of our training. This one - "I'm not ready for that."

"I'm not ready for that." is a healthy approach to training things that overwhelm us.

Here are a couple of counters to the standing guard pass to help your game. Years ago I learned the second of these moves at a workshop with Renan Borges. I was still a white belt at the time, and even though I really liked the move, it wasn't something I was ready for.

I filed it away in the "I like this, but I'm not ready for it right now. I'll do my best today, and someday I'll come back to this." A few months ago, it started reappearing in my rolls and here's how I integrated it and hopefully you can too. When you are ready.

Sickle Sweep - place the feet in the hips as they stand up. As they push the leg down, rotate your foot inside to help with leverage. Not necessary, but it can give a good bite on the hip.

Use your other arm to attack the ankle with an underhook. Push up with the foot in the hip, and slice the back of the ankle with your leg as you hold the other ankle.

Deep Pass Defense - when they step through more aggressively, it is difficult to get the leverage to apply the sickle sweep. Here we shoot the arm through the leg following with our head and shoulder. Think of the hand as the tip of the arrow, and the head is the feather.

Place the back of the tricep on the back of the leg to help finish rotating through. No need to pull the leg all the way through, and it is faster to use the shin with the other leg. Grab the ankles and leverage up.

You can then take the back, or attack the ankles.

Defending Against the Bear Hug - PASS vs. FAIL

Jumped from behind? Your opponent got position on you? No matter how it happened, it's a bad place to be. Join me and my special guest Sensei Ando as we show what to watch out for, and how to make one of the most commonly failed escapes, succeed.

Jumped from behind? Your opponent got position on you? No matter how it happened, it's a bad place to be. Join me and my special guest Sensei Ando as we show what to watch out for, and how to make one of the most commonly failed escapes, succeed.

►For more of Sensei Ando's tips and tactics, SUBSCRIBE to Sensei Ando: https://www.youtube.com/user/AndoMierzwa

►Also visit Sensei Ando's website here: http://senseiando.com

First thing to do is to drape the hands to defend the choke, and drop your stance to keep your center of gravity lower, making it difficult for your adversary to pick you up.

Next, it is important to realize that standard escapes with splitting the arms do not work unless your opponent makes a mistake. The objective of holding you from behind, unless a multi-attacker scenario, is to pick you up and slam you. This means, our adversary is going to grab us lower, around the elbows; making it impossible to split the arms and slink out.

After establishing control of the arms and a good wide base, start using your hammer fist attacks to the groin, combined with foot stomps to rattle your opponent and get them moving around. Remember to always use the 'outside' foot to stomp. Never the inside.

Since our opponent has widened their stance for stability and to avoid the attacks we are making, we can now make our first attempt to escape using the underhook to the single leg takedown.

Caution

Be careful not to walk out and stop. This is transitional only. We have to immediately move to the takedown, or re-establish our base and position if something went awry.

As you shoot for the single leg, if the opponent moves, or you do not have enough mobility to get a strong hook/position, then we can abandon that and use the elbow splitting escape that previously did not work. After all the moving around, chances are that the grip they had before, has slipped higher on our arms and we can make our secondary attempt a success.

Where to?

Once we're out of the bear hug, we want to look for a follow-up move to secure our position and turn the tides. Sensei Ando has a good go to he shows, followed by a variation I would use.

After the elbow split - immediately snag the neck hook position to keep control.

Ando

Attack the head with a knee to the face to soften them up. Maintain the neck hook and do not give up a strong position. Immediately follow up with a shoot underneath using the elbow in the groin to bring them over the back for a Fireman's Carry Takedown.

Tips: Sensei Ando makes note to watch the danger of the headlock as we're slipping out. Good tip. He also points out to tuck the foot so they don't land on you and break your toes.

Randy

I start off the same way and attack the head with a knee. I'm anticipating the block, but if they don't, even better. We're done here. If they do block as planned, then I shoot over the top and thread my arm under the neck all the way to the other underarm. Clasp the hands, and we have a nice guillotine setup. Use your shoulder to drop weight on them making it difficult for them to posture up and move. Follow this up with a nice reaping leg takedown variation for the finish.

The finish is up to you and your skillset. You can chuck them and go to a ground and pound, pound the ground package, or you can hold on to the guillotine, keep a solid position on the same side of the body as you started on, and finish the choke you already have.

Mantis Captures Prey - How to Stop the Underhooks

The underhook is a powerful tool in the hands of an opponent who knows how to use it. They have leverage, control, and setups for numerous takedowns. So how do we stop our opponent from getting the underhooks? With this awesome move from Taijiquan called Fist Under Elbow, and what I like to call Mantis Captures Prey.

The underhook is a powerful tool in the hands of an opponent who knows how to use it. They have leverage, control, and setups for numerous takedowns. So how do we stop our opponent from getting the underhooks? With this awesome move from Taijiquan called Fist Under Elbow, and what I like to call Mantis Captures Prey.

In this video, we'll walk you through 1. The dangers of the underhook. 2. How to shut it down. 3. Counters from our opponent to watch out for, such as the 2nd hand. 4. Spear Hands, Eagle Claws, and Reaping Legs. 5. Hook, don't Reap - how to vary the technique based on our opponents position.

Like the video? Don't forget to hit subscribe.

Defending the Worst Position Ever!!

The High Mount combined with striking is a deadly combination. This is by far, one of the worst positions you can get stuck in on the ground. The traditional BJJ escape for mount - bridge, trap, and roll doesn't work quite yet, and meanwhile our opponent is raining punches on us, and bringing the thunder like Poseidon.

All too often, we panic in this situation and end up flailing, or trying to grab arms. Here we show a technique we call - 'Shield Up / Shimmy Up' to help you deal with this problematic position. We have to work from where we are, not where we want to be.

The High Mount combined with striking is a deadly combination. This is by far, one of the worst positions you can get stuck in on the ground. The traditional BJJ escape for mount - bridge, trap, and roll doesn't work quite yet, and meanwhile our opponent is raining punches on us, and bringing the thunder like Poseidon.

All too often, we panic in this situation and end up flailing, or trying to grab arms. Here we show a technique we call - 'Shield Up / Shimmy Up' to help you deal with this problematic position. We have to work from where we are, not where we want to be.

Like the video? Don't forget to hit subscribe.

Training Your Elbows and Joint Locks (Chin Na)

Joint locks (Chin Na) are fun!!! If you are into pain that is. ;-) Seriously, standing submissions are very cool; unfortunately, they can be extremely difficult to pull off for real.

Here is a more advanced drill to help you train ways to...

Joint locks (Chin Na) are fun!!! If you are into pain that is. ;-) Seriously, standing submissions are very cool; unfortunately, they can be extremely difficult to pull off for real.

Here is a more advanced drill to help you train ways to flow your fighting into those nifty locks. In order to make this drill easier, you'll want to have some knowledge of elbow strikes, and joint locks before doing this.

As Vincent and I throw elbow strikes, it forces the other person to counter the strike and place themselves in a position where we can setup a joint lock, rather than trying to attack a completely resistant opponent. This is a softening the target, or creating a distraction so we can affect the lock.

Enjoy!

Like the video? Don't forget to hit subscribe.

►SUBSCRIBE on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/mantisboxers

Collapse and Fall Into Ruin - (Beng 崩)

A huge thanks to Gene Ching and the team at Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine for publishing my article this month. Such an awesome presentation! Thank you to my team - Holly Cyr, Vincent Tseng, Max Kotchouro, Bruce Sanders, and Sean Fraser for your assistance in making this happen. I am honored.

A huge thanks to Gene Ching and the team at Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine for publishing my article this month. Such an awesome presentation! Thank you to my team - Holly Cyr, Vincent Tseng, Max Kotchouro, Bruce Sanders, and Sean Fraser for your assistance in making this happen. I am honored.

The article is an expose on the Mantis Boxing principle of Beng (Crush, or to Collapse and Fall Into Ruin). You can read the rest of the article 'Collapse and Fall Into Ruin' in the July/Aug issue on store shelves now, or available online.

BJJ Mount Attacks For Smaller Fighters

Fighting bigger opponents can be frustrating when we try and control the mount position. I know I avoided the mount most of the time as a BJJ White Belt after getting tossed around repeatedly. After a while, I started using the high mount to setup some attacks. Here's are two videos highlighting some attacks from the mount.

Fighting bigger opponents can be frustrating when we try and control the mount position. I know I avoided the mount most of the time as a BJJ White Belt after getting tossed around repeatedly. After a while, I started using the high mount to setup some attacks. Here's are two videos highlighting some attacks from the mount.

Moving closer to the head helps maintain the control needed, but many opponents will seal their arms up to try and stop arm bars, and americanas. Here's a tool to crack open that pesky shell and get the arms exposed for attack.

Like the videos? Don't forget to hit subscribe.

Why is BJJ Easier than Boxing/MMA?

"Why is BJJ easier than Boxing?" This was a question proposed to me last year when we were taking submissions for the Swamp Talks videos. Truth be told, it was a question that made me uncomfortable at first, as I assumed it would be misconstrued. This question, out of all of them, really stood out to me and made me think.

It made me think about something I hadn't previously considered. Something that was clearly...

Learning to Walk Again With Martial Arts

"Why is BJJ easier than my stand-up fighting art?" This was a question proposed when we were taking submissions for a podcast. Truth be told, this question out of all, made me uncomfortable. I assumed it would be misconstrued by the internet tigers, and they would all pounce. “What do you mean BJJ is easy!?!?!” This question, out of all of them though, really stood out to me.

It made me think about something I hadn't previously considered. Something that was clearly on the mind of more than one of my students who train multiple fighting modalities. At first, I opted not to address this question, even though I left it on the list. I needed more time to think about it. To ponder the implications. It wasn't until a few months later that I had formulated a decent answer and can now commit to writing it out. The question:

“Why is it so difficult to get the stand-up game compared to BJJ?” Let's break it down by each element and hopefully make some sense of it. BJJ is not easy, and I know that was never the intent of the questioner, but it is certainly easier than learning stand-up fighting.

Crawl. Walk. Run.

When fighters get frustrated with footwork, I ask them - "Did you walk out of the womb?" A rhetorical question, to set up the greater lesson - First we laid on our back kicking our legs. Then we laid on our belly for a while doing push-ups. Next we started to crawl. Then we started to use our arms to climb, and stand. Once our legs gained strength, we began to take our first steps.

After falling quite a few times, we got the walking thing down. Later we started to run. Fast forward to here and now. We are learning to walk all over again, in a way that makes us effective boxers. But rather than laying there kicking our legs for a while, we are insisting we should be able to run right away. Therein lies the problem.

You Monkey!

Monkey Staff - 2003

At our roots we are primates. Our instinctive method of striking is large, powerful swings that maximize our anatomical structure. This creates power, but leaves little in the way of protection.

In martial arts (boxing, kickboxing, karate, etc.), we learn a new way of striking. Ways completely counter to our instincts, and some that will build off of them. These new methods we learn can provide power while simultaneously offering a guard for helping to protect our own head in a fight.

Striking seems simple from the outside. I believe that is why I see so many people baffled by the amount of time it takes to get good at it.

I read a blog post from Dan Djurdjevic yesterday speaking about 'what it means to be a beginner' (see his post here). In his article he brought up boxing, and the amount of time before a boxing coach thinks you are moderately skilled at striking. This was new to me as I am not in the western boxing circuit that focuses solely on striking (no kicks, takedowns, elbows, or knees like mantis boxing). Dan claimed, 4 years for proficiency. That coaches do not consider you close to stepping into a ring with a pro-fighter until much later. This is a martial art modality built around 'STRIKING AND FOOTWORK ONLY'. Yet four years of training before an amateur level is achieved by the average person.

It is healthy to have realistic expectations. A heavy bag routine a few days/week can help increase our striking game and cut down on the mistakes we make. Remember, it's about building motor function. The more we punch, the easier it becomes to tweak and fix.

Building Blocks

We may have come with a natural affinity for striking, even if a coach tells us it is the wrong way to fight. But when it comes to blocking, we will definitely have more limitations to proficiency. Our natural instincts tell us to shield up, turn into a ball, or flail wildly.

When we enter martial arts, these motions are new, and we have to refine and work on them. Which includes technical elements, structure, timing, position. The training time for this can be fairly quick with proper partner training, but is not enough by itself. Unfortunately we can't stand there and block all day long. Eventually they will find a hole in our defense.

Your 'Other' Left Foot

‘Soooooo…we thought we knew how to walk...?’ Since we spend a large part of our life moving around on our feet, you'd think footwork would be a given. Nope. On the contrary, building a proper stance and then learning how to move in that stance, takes a lot of repetition for it to become second nature. Until we achieve said proficiency, we will have holes in our game that are easy to capitalize on for a moderately skilled opponent.

Shuffling, stepping, circling, angling, cross circle steps, spin outs, change steps, are a lot of meat on the table. In order to polish these, we'll need to spend time working it out. The nice thing is, we don't NEED a partner to practice footwork. Just a small open space.

Just for Kicks

As if all the aforementioned challenges were not enough, now we're thinking we should be able to throw kicks with ease. To go from a bi-ped day in and day out, to now standing on one leg while breathing, relaxing, and kicking someone hard enough to make them think twice about attacking us again. This one is definitely outside the normal realm of human motion and fighting instincts.

Kicking is going to be a skill that takes on a focus on it's own. There are entire martial arts built around this one modality (see tae kwon do). As with striking, if we have a bag we can beat on, it will do leaps and bounds to help us get our kicking to a decent skill level. Once we have the repetition, and we aren't falling on our ass every time we lift one leg off the ground, then we can grab a partner and focus on targeting, plus timing.

Kicks expend more energy, and create bigger liabilities (depending on the type of kick). Wasting them on targets that are not open can bleed out our endurance, and leave us sucking wind. Knowing when and where to throw the kick is the key to the leg game.

Throwdown!

Next on our list is another completely foreign skill that we did not come pre-packaged with. Beyond the basic charge and tackle, throwing another human being is an art form. Also, as we saw with kicking, evidenced by the fact that there are entire martial arts styles built around this pillar as well. Styles such as Shuai Jiao, and Judo. Both comprised of techniques not inherent to human instinct.

Learning the technique is one thing; building the timing for the perfect execution is a highly advanced skill that requires years of practice and sparring.

Chin Na class. Averill's Martial Arts. circa 1999

Locked Up

Joint locks (Chin Na) are another highly technical aspect of martial arts. They require a certain finesse to be effective and become proficient in. There are tons of limb locks out there, but knowing how, when, and on who we can use them is sometimes confusing, and almost mythical. Combine this with timing these off a punch, or grab, and the difficulty increases exponentially.

"Repetition is the mother of all skill." This is the truth with joint locks especially. The more we train them, the better we will get, and the more sensitivity we will have to make adjustments when things change on the fly. Check out Size Matters for more on the intricacies of joint locks and why they usually do not work.

Hooked Up

Once the range changes, we now have to deal with the clinch and getting tied up with hooks. Learning to escape and dominate the clinch, as well as throwing elbow strikes, and knee strikes, is yet another skill we throw in the mix. Like kicking and punching before, practicing these on a heavy bag, or throwing dummy can help knock off some of the repetition and get our skills kick started, but we'll definitely need to apply it with a partner to get the full benefit.

So, "Why is BJJ easy?"

Part of my discomfort with this question was, as I said in the beginning, that I knew it would be misconstrued. I understood what the individual really meant to say, but I was afraid others might take it as "BJJ is EASY!?!?! Say, What?!?!?" That was not the implication in the question.

BJJ is not easy, and the person asking the question struggled plenty with that training as well. The elements of the question have merit though. Why does it seem easier to become skilled in BJJ than with stand-up arts?

Brazilian jiu-jitsu, at least most sport BJJ, is heavily focused on the ground game. That means we are working on a single plane. Our body weight is fully supported across a wider surface than two feet can come close to attaining. This allows for ease of movement with our arms and legs available to focus on attack, and defense, rather than balance, mobility, striking, kicking, defense, and grappling all at once.

Additionally, unlike all the items we listed in stand-up that have nothing to do with our instincts - jiu-jitsu is much akin to our natural instinctive body movements, and innate self-defense skills. Like tiger cubs that practice sparring before leaving the safety of their mother, so to do we practice fighting when we are young, pliable, and less likely to hurt one another, and ourselves. We can see this when we watch untrained siblings go at one another in the living room of our home. They have a natural inclination towards wrestling, grappling and that style of movement. If they had fur and tails we’d think they were monkeys.

We Don't Need Another Hero

We all have hero's we see in films, or in the ring/cage. We see people we admire for their skills. But that's it, we see the results. The results of their effort. What we do not see, is the countless hours of training they had to go through to get there. The blood, sweat, tears; the pain, the setbacks, the injuries.

Many people find Bruce Lee to be an inspiration. There exists a seemingly invisible effort behind his movements, joined by every other icon we may have - Mike Tyson, Muhammad Ali, Rhonda Rousey, Holly Holm, etc. When we see them, we see them in their prime, or entering their prime. We see them after years/decades of training, practicing, sweating, sacrificing.

There is no 'short cut' to gaining "mad skillz". We have to do the work. In order to do the work, we have to enjoy the art, the people we train with, and stay focused on our goals. If we do not enjoy the process, then we need to vacate the space and find another sport we enjoy.

The Sum of All Parts

So in summary, if we look at the base elements I listed above, we can quickly see how things can seem overwhelming and hard to accomplish. It's normal. Any skill we wish to achieve in life, takes time to master.

On top of each individual component of stand-up fighting being an art in and of itself, trying to tie all the pieces together while our brain is in the early stages of learning, is thrilling, and yet seemingly insurmountable at times. Push through this and we will be rewarded.

When we walk into a stand-up martial art like mantis boxing, at it's essence - we are being told that we do not know how to walk, talk (lingo/jargon), punch, kick, grapple, or throw. We are starting fresh. This is a great time, and wonderful feeling that we’ll one day miss when we are more experience. After a few months, when the newness wears off, we start to feel the deck is stacked against us. Things we took for granted in everyday life, are now being retrained, and in the interim, someone else is taking advantage of our newly realized deficiencies. This can be overwhelming, humbling, and at times seem unattainable. It isn’t.

Take a deep breath, relax, and focus on enjoying the process, the people we train with, and have fun with learning. If we think in terms of belts/time, or years to mastery, we will forget why we started doing this in the first place. We’ll talk ourselves out of the arts altogether. Live in the moment. Enjoy the journey.

Thank you Max Kotchouro for some of the photos and video.

The Truth on Effective Strike

Effective Strike (Xiao Da), is the Chinese principle of striking to vital targets, or targets that have more destructive impact than other areas of the body. This is a common concept in many styles of martial arts. I recall the first time I showed up for Tae Kwon Do/Hapkido class back in 1991 - my teacher said - "Want to kill a man? Hit here, here, here, or here." I was happy, but stunned.

reprint of an article published in 2013 in the Journal of Seven Star Praying Mantis -

Xiao Da - The Truth on Effective Strike (Journal of 7 Star Mantis vol. 4, issue 4/Northern Shaolin Praying Mantis Institute and Association 2013)

Targets

Listed below are the targets and the effects a person experiences when being hit in those regions.

8 Head Targets

Throat

Side of Neck

Back of Neck

Jaw

Nose

Eyes

Ears

Temple

12 Body Targets

Shin

Knee

Outer Thigh

Inner Thigh

Groin

Bladder

Rib (Floater)

Kidney

Liver

Stomach

Solar Plexus

Collar Bone

Photos courtesy of Max Kotchouro

Cervical Spin - Downward Elbow Strike

Effective Strike (Xiao Da), is the Chinese principle of striking to vital targets, or targets that have more destructive impact than other areas of the body. This is a common concept in many styles of martial arts. I recall the first time I showed up for Tae Kwon Do/Hapkido class back in 1991 - my teacher said - "Want to kill a man? Hit here, here, here, or here." I was happy, but stunned.

I thought to myself - "WOW! Cool!!!" Followed by - "wait...why would you tell someone that in their first class? Isn't that dangerous information to hand out to strangers? After all even US Army Basic Training Hand to Hand Combat didn't teach us that!". I chalked it up to him just being half psychopath since he spent most of his life training elite South Korean Special Forces Soldiers in Hand-to-Hand Combat.

It was some time later in my martial arts career that I realized why this information wasn't so dangerous after all. The reason is simple. If you don't train it, you won't use it. Effective Strike is a skill like any other. It needs extensive practice and proper training in order to be effective in real combat, or in other words - to manifest itself under stress. In said Tae Kwon Do class, we never used finger strikes, throat chops, or did any sort of training that incorporated strikes to these vital areas; we simply kicked, punched (less), blocked, and smashed our shins and forearms on one another till bruised an battered.

Brachial Stun using Slant Chop

Train Like You Fight, Fight Like You Train

I like to use the terminology - train like you fight, fight like you train. In your Kung Fu training, the constant focus of hitting to Effective Strike targets is crucial to making this habitual. There is no time to think in a fight. One must react and react appropriately; which is the whole objective of proper training.

So when should you learn this skill? Ideally the sooner the better, especially for smaller fighters. Smaller fighters lack the power that a larger or heavier opponent can produce, so this skill is crucial for us. Being able to hit someone in a targeted area means that your strikes pack more bang for the buck.

With that said, one needs to learn how to properly punch first, before focusing on Effective Strike. Trying to perform Xiao Da from Day One, gives the brain too much to focus on at one time. A beginner should be more concerned with proper striking, blocking, guard principle, and defense first. Once Xiao Da is properly introduced, aim for these targets with every strike in your arsenal.

After you have learned it, you can then veer off to other non-effective targets that may lure or distract your opponent; creating what we call Open Doors to the effective targets we want. This is necessary because an opponent with a good defense will 'require' you to 'open doors' in order to hit his covered targets.

Training Tips

These vary based on whether or not you have a training partner. I did not have a partner to use when I wanted to integrate this into my fighting, so I took colored price stickers used in yard sales, and I plastered them on my heavy bag in the general target areas on the human body. I then practiced various combinations striking to these targets. To test them, I sparred with other people.

For those with a partner, I recommend a great technique called 'Walk the Body', passed down to me from a mantis boxing coach on the west coast. Walk the Body has one person standing still (in their fighting stance is fine) while the other practices slow and very low power combinations to targets on their partners body.

As you grow more comfortable with the targets, the complexity increases by having your partner put their hands up in a defensive fighting position forcing you to move their arms. Following that, you need striking combinations, that the partner blocks, so you can open doors to the Effective Strike targets you wish to hit using solid striking combinations.

Note: this is not a fast paced exercise and requires patience, cooperation, and hours of practice to become second nature. It challenges your critical thinking skills once you add the complexity of combinations versus a live defense. Done properly however these strikes will become automatic and ingrained in your skill set.

Ear Claw

DIM MAK - The fallacy of pressure point based combat

Early in my training I met people, and still do from time to time, that have little knowledge of martial arts, but they talk about Dim Mak (pressure point striking) from books they've read, or videos they've watched, or even some Hollywood movie.

You can find videos online of teachers knocking out students at demonstrations to show Dim Mak, and all the supposed power one can have over other human beings by hitting them in these targets. People are fascinated by this and very enthusiastic. I can understand why, the idea of knocking out someone else with such ease is...alluring! Unfortunately, while some of these are legitimate strikes to real targets, some are incredibly finite and difficult to get to.

In a previous article, Size Matters - In Chin Na I discuss 'gross' versus 'fine' motor function in combat. Just like finite Chin Na skills, high precision striking is less reliable when we are under stress, AND when our opponent is trying to hit us back. That's the live, active, and moving opponent that is also trying to ‘take your head off’ component.

This complicates things and makes it much more difficult to perform a finite strike to a small target area. So unless you're Luke Skywalker firing your torpedo at the Death Star, give up on the idea, and stick with something that will work.

Natural armor - in addition, a human being under the affects of adrenaline in combat (never mind the affects of drugs), is more resilient to these strikes. It really sucks when you're in the thick of it and your silver bullet doesn't really kill the werewolf! This is why it is better to learn multiple targets, strike in combinations that you would normally throw, and cover your bases in case you miss the first target. Meaning, you missed but it still hurts them like hell!!!

Targets Defined

Temple Strike using Backfist

8 Head Targets

Throat - Crush the larynx making it difficult to impossible for opponent to breathe

Side of Neck (Brachial Stun) - Knock out blow, or excrutiating pain at the least

Back of Neck (Occipital Lobe) - Knock out blow

Jaw - Break or Dislocation. Extreme pain.

Nose - Pain. Bleeding. Watery Eyes causing reduced vision.

Eyes - Loss of sight. Extreme pain.

Ears - Tear them off for extreme pain.

Temple - Knock out blow. Extreme pain. Disorientation.

Knee Break using Cross Kick

12 Body Targets

Shin - Extreme pain and discomfort.

Knee - Break/Dislocation. Extreme pain. Loss of Mobility.

Outer Thigh - A solid kick to this target can cripple a fighter and make them think twice about closing distance.

Inner Thigh (Femoral Nerve) - Identical to the Outer Thigh, this target causes excruciating pain.

Groin - Extreme pain and discomfort. Potentially cripple opponent.

Bladder - Pain and discomfort. Possible bladder release. (you figure it out)

Rib (Floater) - Break. Extreme pain and discomfort. Possible breathing effects.

Kidney - Potential knock out as well as extreme pain.

Liver - Knock out blow. Extreme pain/discomfort.

Stomach - Knock out blow. Extreme pain/discomfort.

Solar Plexus - High concentration of nerves. Also the meeting point of the heart, liver.

Collar Bone - Break. Extreme pain. Loss of use of arm on that side. Harder target to hit and not effective on everyone.

The Dirty History of Tai Chi

The history of Tai Chi, correctly called Tai Ji Quan, disseminated to the masses, is often a mythical story that involves an art form thousands of years old with Taoist immortals, monks, and fairies. Commonly it is propagated that a non-existent type of magical energy, will heal the practitioners body and/or throw opponents without ever touching them. This is a fictional portrayal that in the West we call a fairy tale and in the East they call wu xia.

The history of Tai Chi (taijiquan, supreme ultimate boxing) is often taken with too much salt. The prevalent history disseminated to the masses often involves a mythical backstory thousands of years old, which includes: Taoist immortals, monks, and fairies. It is commonly propagated that the style of Tai Chi contains and revolves around a type of magical energy (known as qi) that will heal the practitioners body and/or throw opponents, without ever touching them. This fictional portrayal in the west would be known as a fairy tale, in China it is called ‘wǔ xiá’ (武侠), martial arts stories in theater/fiction popularized during early 1900’s China.

The notion that one can achieve unequivocal power, something akin to a superhero, without ever performing a day of ‘rigorous’ training, exertion, or hard work, is certainly the stuff of movies, myth, and legend. In contrast, the truth of tai chi’s history is far less enchanting to the laymen dabbling in an exotic art. The truth involves laborious acts, physical exercise, redundant practice, mental endurance, self-discipline, perseverance, and a history full of bloodshed, violence, and oppression.

General Qi Jiguang. Source: Wikimedia

The more accurate and verifiable history at the time of this writing shows that tai chi was developed roughly 400 years ago in Chen Village, Henan Province, China. It was known as less formally as ‘Cannon Boxing’, or the Chen family style. Like many Chinese martial arts it included hand-to-hand combat techniques common to the region, area, and time period. In 1560, General Qi Jiguang developed an unarmed combat system to train a militia to fight the wokou pirates. A group of Japanese pirates, which included Chinese ex-soldiers, privateers, and ruffians were pillaging the coastal villages and sea traffic. Based on the chapter in Qi Jiguang’s manual on unarmed combat, and the included illustrations, it appears by the trained eye that many of the depicted hand-to-hand combat methods are found in what is now known as tai chi. This points to a common pool of knowledge of fighting techniques.

During the mid 1800's Yang style tai chi was created by founder Yang Lu Chan. Yang, lived and studied in Chen Village and later went on to create his own system originally called 'Small Cotton Boxing'. Now known as Yang style tai chi, or taijiquan.

While many of Yang’s techniques mirror the Chen family boxing style, Yang included some of his own methods and merged them with the techniques of the Chen style, as any fighter will do throughout their martial journey when introduced to effective combat methods that they wish to amalgamate into their own art.

Yang’s life (1799 - 1872), or the life around him, was no stranger to violence and upheaval. Throughout his adult life he bore witness, knowingly, or unknowingly, to the impending collapse of China’s final dynasty, the Qing (1636-1912). Events happening all around Yang during his life include catastrophic flooding of the Yellow River (Huang He) (1851 - 1855, and many many more), famines, droughts, drug epidemics, two wars with the west (see Opium Wars 1839-1842, and 1856-1860), multiple rebellions (see Nian rebellion 1851-1868 and Taiping rebellion 1850-1864), and the encroachment of western powers on the Chinese populace, especially in and around trade ports.

As a result of losing both of the aforementioned wars, China was forced through treaty to pay reparations to the western powers, mainly by opening previously closed trade ports in the south and the north.

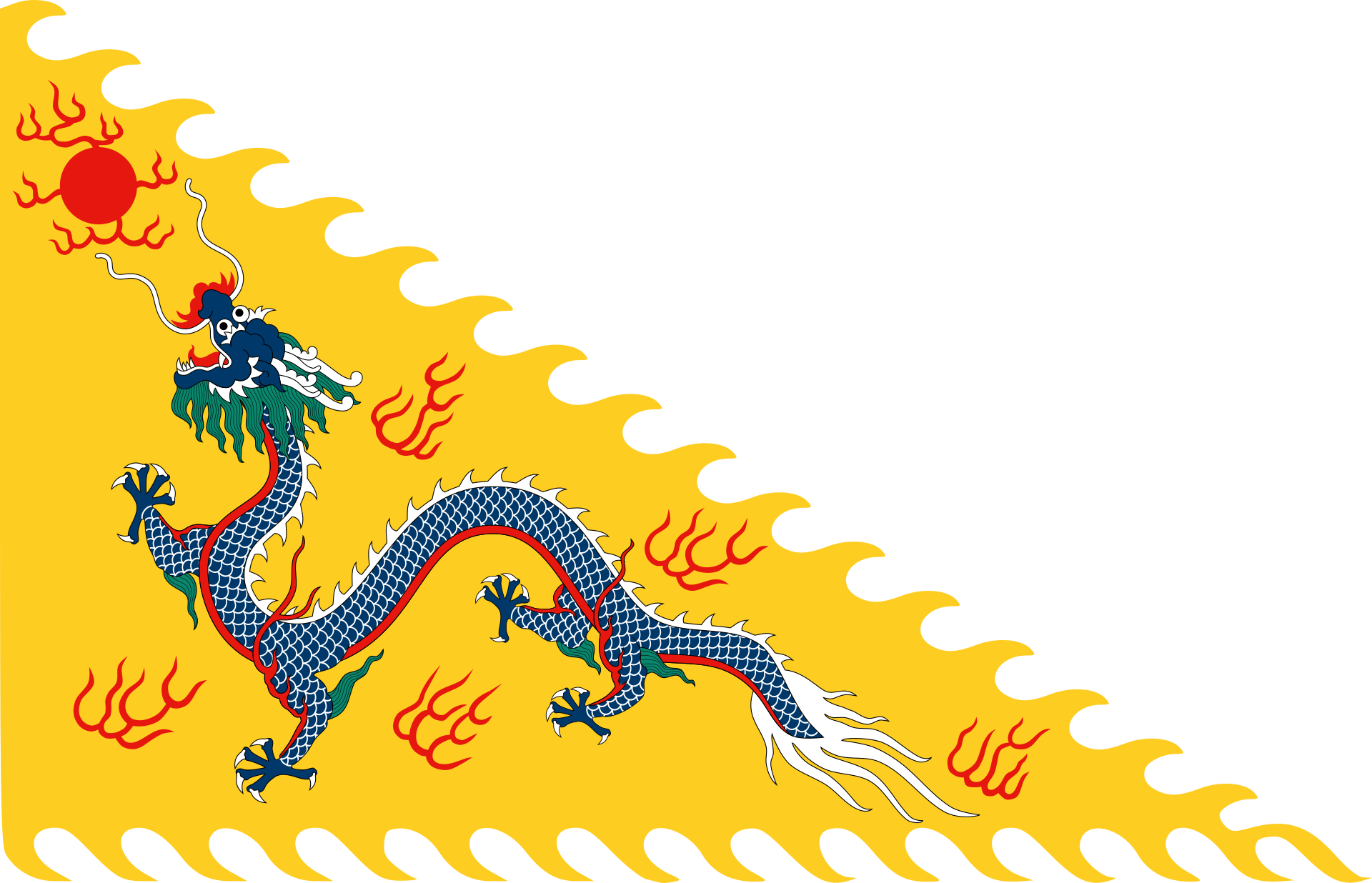

Imperial Standard of the Qing Emporer

Yang Lu Chan at one point in his life is recorded as being hired by the Qing court to teach armed, and unarmed combat to the imperial guards of the Manchu court in Beijing. Yang also disseminated his boxing art to his family.

Around the turn of the 20th century, decades after Yang’s death, the Chinese became disenchanted with their martial arts after repeated embarrassment in their confrontations with the west. More specifically incidents involving armed and unarmed combatants known as boxers, versus soldiers with firearms. Arguably the most famous of these incidents is known as the 'Boxer Rebellion', or more accurately the ‘Boxer Uprising’ (Joseph W. Esherick - The Boxer Uprising), which transpired over a four year time period with various encounters. The uprisings took place in Shandong, Hebei, and Tianjin provinces, as well as Beijing itself.

Port of Chefoo circa 1878 to 1880. Edward Bangs Drew family album of photographs of China, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Historical Photographs of China - https://hpcbristol.net/visual/Hv37-02

A century prior to this China was one of the most powerful civilizations on earth, with one of the most formidable military forces in existence. However, the industrial age in the west brought substantial change to warfare, along with the ability for nations to project global power in greater magnitude than ever before.

Although martial arts was considered beneath the scholar class, it was prevalent with boxers, soldiers, and guards in the employ of biaoju (security-escort companies). Local militia-men, sanctioned by magistrates commonly used armed/unarmed martial arts methods to quell local bandits and keep the peace. The Qing government in the 1800’s was preoccupied and impotent to respond to many smaller internal issues. The lowest expression of martial arts was associated with criminals, gangsters, ruffians, or charlatans which the Jing Wu and early 1900’s Chinese martial arts community tried to erase, or reverse.

The ‘boxers vs firearm’, or rather, antiquated military tactics versus modernized, industrialized weapons and strategies incidents that took place around 1900, likely further cemented the general public’s poor opinion of their nations martial arts, and of the ‘boxer’ overall. Three hundred years prior during the Ming dynasty General Qi, in his second book, published two decades after the first and post wokou battles experience, considered the act of training troops in hand-to-hand combat a rather fruitless endeavor when compared to the rapid and effective weapons training such a spears and matchlocks. This is evident since his second book omitted the unarmed combat chapter altogether.

Battle of Lafang 1900. Source: https://pin.it/5uubzq3xry77n5, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By the turn of the 18th to 19th century the Chinese having battled the western power’s sponsored opium crisis, repeated mass famines, floods, droughts that killed millions of people; rebellions that also killed millions more, and in addition to disease epidemics, were being called the 'sick men of Asia' by the international community. For a culture that was once in the not to distant past, more powerful than any other nation on earth this was humiliation on an epic scale.

At the end of the Qing (1910’s) and the beginning of the Republican era, a movement was initiated to change this stigma. A nationalist effort was undertaken to strengthen the populace and remove this cultural blight, or poor reputation. As a part of this movement and perhaps in an effort to keep their national arts from dying, Chinese martial arts teachers were commissioned to teach their methods for health, strengthening, and fitness, rather than for fighting.

This saw the creation of organizations such as the Jing Wu Athletics Association (circa 1910) of which tai chi, specifically Yang style, was a significant part of, as well as later the Nanjing Central Guoshu Institute in 1928. The directive of Jing Wu was primarily to improve health, and combat the 'sick men of Asia' label. Teaching physical fitness and health to affect positive national change. The Nanjing Guoshu Institute also propagated Chinese martial arts, and employed none other than Yang Chengfu, grandson to the progenitor of the style.

Yang Cheng Fu clearly had an entrepreneurial spirit that would help proliferate not only the Yang family art, but by proxy their predecessor, the Chen family, as well as the Yang offshoots of Wu family style Taijiquan, and Wu Hao style. Yang Chengfu took his grandfathers boxing art and taught far and wide, spreading it to the general public for health and wellness purposes around 1911.

Chengfu incorporated slow motion practice and longer movements as the focal point, removing much of the fighting application and combative elements taught by his grandfather, father, brother, and uncle. Thus was born a form of exercise that was all at once accessible to the young, old, weak, sick, and those of poor physical condition; to which rigorous exercise was not possible.

Prior to this Yang family taijiquan was taught strictly for combat, or a method of violence, or rather, defending against violence. It involved such skills as striking, throws, trips, takedowns, joint locks, sparring, fighting, and weapons training.

Forms practice (tào lù 套路), and push hands (tuī shǒu 推手) in contrast to present day, were likely a very small portion of the training. It is questionable if push hands had a significant role in the traditional combative training outside of skill building. It is possible that this portion of the training was derivative of the scholar class slumming in the martial arts world years after the art lost its teeth. A ‘game’ for people uninterested in fighting to pretend they are fighting.

It is also possible that given the heavy focus of the Manchu on wrestling, which was significant with the Han as well, that push hands was a tool for training wrestling skills in said competitions. The strategy of pushing an enemy in battle is ludicrous unless pushing them to the ground, or off a cliff. However, pushing someone outside a ring, or off a platform (lei tai matches) in order to score points, or win, holds a great deal of validity.

Qianlong Emporer observing wrestling match. Source: WikiCommons

Due to Yang Chengfu's efforts, and others around him, Yang style went on to become extremely popular, the most widely proliferated form of taijiquan throughout the world even to this day. The style’s true nature however is evident by some writers of the time:

Gu Liuxin writes of Yang Shaohou (Yang Cheng Fu’s older brother 1862-1930)

He used, “a high frame with lively steps, movements gathered up small, alternating between fast and slow, hard and crisp fajin (power/energy), with sudden shouts, eyes glaring brightly, flashing like lightning, a cold smile and cunning expression. There were sounds of “heng and ha”, and an intimidating demeanor. The special characteristics of Shaohou’s art were: using soft to overcome hard, utilization of sticking and following, victorious fajin, and utilization of shaking pushes. Among his hand methods were: knocking, pecking, grasping and rending, dividing tendons, breaking bones, attacking vital points, closing off, pressing the pulse, interrupting the pulse. His methods of moving energy were: sticking/following, shaking, and connecting.”

1949 Taiyuan battle finished. Source: WikiCommons

Three decades after Chengfu’s popular introduction of this rebranded art to the people, the Communist Party took control of China. As in past rebellions and changeovers of power, they once again outlawed the instruction of martial arts for the purposes of fighting. Mao Zedong, ever a student of history was well aware of the number of uprisings, rebellions, and dynastic turnovers associated with temples, and boxers. He burned the temples and banned the boxers.

During this period in the mid twentieth century, many traditional martial artists fled the country or were killed. The restriction by the government was certainly not in fear of a boxer, spearman, or swordsman attacking a tank, or machine gun nest, but rather due to a need to control the populace, a task exponentially more difficult when it involves submitting those trained in fighting arts (disenfranchised privateers, aka pirates). Martial training empowers individuals and empowered people are less willing to blindly succumb to oppression.

In 1958 after the period of unrest during the Communist Revolution (circa 1946 to 1949), China formed a committee of martial arts teachers. Choosing from a pool of those who stayed behind and used their martial arts training for coaching health/fitness, and/or those who had returned to the mainland from their exile.

The committee created what are known as the ‘standardized wushu sets’ - choreographed forms of shadow boxing summarizing and abbreviating the broad spectrum of China's legacy martial arts styles.

The wushu committee created the standardized sets for unarmed and armed styles, streamlining hundreds of styles in the north, and south that shared common techniques into one compulsory set to represent each - long fist (changquan) for the north, and southern fist (nanquan) for the south. In this consolidation effort, a few styles were left to stand alone gaining independent representation. These were, praying mantis boxing (tanglangquan), eagle claw boxing (yingzhaoquan), form intent boxing (xingyiquan), 8 trigrams boxing (baguaquan), and supreme ultimate boxing (taijiquan). Coincidentally these five styles were the advanced curriculae of the Jing Wu athletic association. Had they not been part of Jing Wu, it would be interesting to know if they would have survive long enough to be recognized by the PRC Wushu Committee.

These choreographed sets were then presented to the rest of world in a neat clean package, government regulated, and used to project China’s human martial prowess abroad, to include a trip to the Nixon White House where they demonstrated their skills. These boxing sets left behind the fighting elements of old, replacing them with sharp anatomical lines, clean corners, fancy acrobatics, and gymnastics. They became martial dance with 'timed' routines rather than the violent methods they once were.

As part of this standardization process in the 1950’s, the Yang taijiquan 24 movement form (a.k.a. Beijing Short Form) was created, and not by the Yang family itself oddly enough. This form represented Yang Style taijiquan (against the families approval) and went on to not only be a competition set, but a ‘national exercise’ that Chinese citizens would practice every morning in local parks for decades to come.

As China opened her doors to the rest of the world, westerners glimpsed the large organized gatherings of Chinese citizens performing their beautiful practice of the short form in parks day after day. Foreigners began learning this art while spending time overseas and via teachers who migrated to western countries proliferating their ‘art’ through hobby, or as a means of financial survival. The western world's interest was officially piqued.

Throughout the 1960's-70's and even into the 1980's, there may have existed a reluctance with Chinese teachers to show ‘outsiders’ their national, or personal martial arts, but others did not know the original intent of the art, and continued to spread the empty shell they were handed.

These factors helped contribute to the spread of misinformation, making it difficult to validate much of the material being practiced outside of the ‘standardized’ sets. The Chinese fighting arts were also fast approaching a century of existence without the practical combat usage of the fighting techniques housed inside the forms being transmitted as part of the art.

Without the trial by fire checks and balances that a martial fighting system uses to hold its validity; such as - 'fail to do this technique correctly and you get punched in the face, tossed on your head, or pushed off a platform' - an environment was effectuated that was ripe for esoteric practices, myth, and legend to take over. To include, but not limited to; mysticism, numerology, archaic medicine, fancy legends, mystical energy, and the most contagious of them all…pseudo-science.

While the combat effectiveness waned, the health benefits of modern taijiquan remain steadfast and clear. There have been many studies by qualified medical professionals around the world substantiating the health benefits of routine tai chi practice in one’s daily activities. However, these health benefits are not unique to tai chi, and may be attained through most almost any form of physical exercise such as, but not exclusive to - running, swimming, cycling, dance, tennis, raquetball, and numerous other sports.

There remains though, a primary advantage of tai chi over some, but by no means all other forms of exercise. A low-impact form of physical exercise accessible to those unable to perform rigorous exercise. This is especially important to senior citizens, or those with debilitating injuries who can benefit from movement, but are unable to participate in high impact sports mentioned above.

Modern tai chi, while no longer a martial art is a form of exercise or martial dance, that can be taught to people of all ages, allowing practitioners to move, think, and have fun as a social activity anywhere they go. Whether it be those looking to improve balance, circulation, stress reduction, bone strength, or those who think they are too old to work out, or too “out of shape” - all can find a welcome home in studying the soft styles of tai chi in its modern representation.

Conversely, if one is looking for a martial art for the purposes of practicing and perfecting methods of violence in its traditional sense, then the modern representations of tai chi, or taijiquan are likely not to be pursued.

What we can all stand to discard, are the esoteric pseudo-science methods transmitted by charlatans and those looking to manipulate others for financial gain, or illusions of power.

LEARN MORE…

If you enjoyed this article you may also find the following articles of interest -

Personal Quest

Alongside teaching tai chi movement for well over a decade, my thirst for the combat applications of these moves/forms overshadowed my ability to teach people without discussing, showing, demonstrating, and instructing people in the combat methods inside the tai chi forms as I unraveled them.

I realized, my goals and desires were no longer aligned with the middle aged, and senior audience that was partaking in my classes for the benefit of health and wellness. Rather than cause injury to people who were, intrigued, but not committed, conditioned, or enrolled for such a class, I amalgamated these combat methods into my mantis boxing classes so I could continue to teach them to a captive audience who is there for such knowledge and skill, and would like to put these into practice for their skill set.

While I retired from teaching tai chi for health and fitness in 2016, I remained steadfast in my quest to unlock these combat applications lost to the annals of time. If you would like a small glimpse of the results of decades of work in reverse engineering these amazing combat techniques that are half a century old, check out the following page to see videos of a few of the moves.

Tai Chi Underground - Project: Combat Methods

Bibliography

Wile, Douglas. T'ai-chi's Ancestors: The Making of an Internal Martial Art. New York: Sweet Ch'i, 1999. Print.

Kennedy, Brian, and Elizabeth Guo. Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic, 2005. Print.

Wile, Douglas. Lost Tʻai-chi Classics from the Late Chʻing Dynasty. Albany: State University of New York, 1996. Print.

Kang, Gewu. The Spring and Autumn of Chinese Martial Arts, 5000 Years = [Zhongguo Wu Shu Chun Qiu]. Santa Cruz, CA: Plum Pub., 1995. Print.

Smith, Robert W. Chinese Boxing: Masters and Methods. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1974. Print.

Fu, Zhongwen, and Louis Swaim. Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Berkeley, CA: Frog/Blue Snake, 2006. Print.