The Origins of Wang Lang of Tángláng Quán - 螳螂拳

Wang Lang (王朗) was a military folk hero/warlord in the Eastern Han dynasty (25CE - 220CE). Born in Tancheng County in the south of Shandong near the border of Jiangsu province. Wang Lang’s deeds are recorded and as with other famous figures in Chinese history, Wang was later memorialized and embellished upon in a famous novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. How did Wang Lang become entwined with the history of Praying Mantis Boxing (Tángláng Quán - 螳螂拳) almost 2 millenia later? Is this the same Wang Lang, or was there someone else who founded this boxing style who went by the same name?

Wang Lang (王朗) was a military folk hero/warlord in the Eastern Han dynasty (25CE - 220CE). Born in Tancheng County in the south of Shandong near the border of Jiangsu province. Wang Lang’s deeds are recorded and as with other famous figures in Chinese history, Wang was later memorialized and embellished upon in a famous novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Sacrificing to heaven and earth, the oath at the peach garden, Romance of the Three Kingdoms/Chapter 1 - An illustration of the book - From a Ming Dynasty edition of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (金陵萬卷樓刊本) , 1591 - the original is kept in the library holdings of Peking University 1591

Wang’s bio according to Chine.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

Wang Lang 王朗 (died 228 CE) courtesy name Jingxing 景興, was a high minister and Confucian scholar of the early years of the Wei period. He came from Tan 郯 in the commandery of Donghai 東海 (today's Tancheng 郯城, Shandong) and was, as proficient in the Confucian Classics, appointed gentleman of the interior (langzhong 郎中), then magistrate of Ziqiu 菑丘. In the turmoils of the Yellow Turban rebellion 黃巾起義 he became a follower of the warlord Tao Qian 陶謙, who promoted his appointment as governor (taishou 太守) of the commandery of Guiji 會稽. This region was contested, and Wang Lang had to ward off the warlord Sun Ce 孫策. The warlord Cao Cao 曹操 therefore decided to offer him the post of Grand Master of Remonstrance (jianyi dafu 諫議大夫), and made him concurrently military administrator of the Ministry of Works (can sikong junshi 參司空軍事). When Cao Cao, as factual regent of the empire, was made king of Wei 魏, Wang Lang was made governor of Weijun 魏郡 and "military libationer" (? jun jijiu 軍祭酒), later promoted to Chamberlain for the Palace Revenues (shaofu 少府), Chamberlain for Ceremonials (fengchang 奉常) and Chamberlain for Law Enforcement (dali 大理). When Cao Pi 曹丕 (Emperor Wen of Wei 魏文帝, r. 220-226) assumed the title of emperor, Wang Lang was appointed Censor-in-chief (yushi dafu 御史大夫) and given the title of neighbourhood marquis of Anling 安陵亭侯. Somewhat later he was made Minister of Works (sikong 司空) and promoted to Marquis of Leping Village 樂平鄉侯. Emperor Ming 魏明帝 (r. 226-239 CE) conferred upon him the title of Marquis of Lanling 蘭陵侯 and appointed him Minister of Education (situ 司徒). His posthumous title was Marquis Cheng 蘭陵成侯. Wang Lang wrote commentaries to the Classics Chunqiu 春秋, Xiaojing 孝經 and Zhouguan 周官 (Zhouli 周禮), and wrote numerous memorials to the throne. Most of his writings are lost.

Sources: Zhang Shunhui 張舜徽 (ed. 1992), Sanguozhi cidian 三國志辭典 (Jinan: Shandong jiaoyu chubanshe), p. 36. Ulrich Theobald Copyright 2016

In Romance of the Three Kingdoms Wang Lang

In the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Wang Lang died at the age of 76 in 228. Despite his age, he led a group of soldiers and set up camp to do battle with Zhuge Liang. In the novel, Cao Zhen was defeated by Zhuge Liang. Cao Zhen called for his subordinates to help, and Wang Lang decided to try and persuade him to surrender (even though Guo Huai was sceptical that it would succeed) and engaged Zhuge Liang in a debate, but was soundly defeated. Zhuge Liang among other things scolded him as a dog and a traitor, from the shock of which he fell off his horse and died on the spot. There is no record of this in history, and instead, it is said that he merely sent a letter to Zhuge Liang recommending that he surrender. The letter was ignored.

Luo, Guanzhong (14th century). Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Yanyi)

The Apotheosis of Wang Lang (王朗)

The birth of mantis boxing has been well debated. Some claim it was a product of the Song dynasty (960–1279), while others place it in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The evidence however points to the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) as the likely period of birth, and Wang Lang is a contributing factor to the evidence.

How did Wang Lang become entwined with the history of Praying Mantis Boxing (Tángláng Quán - 螳螂拳) almost 2 millennia later? Is this the same Wang Lang, or was there someone else who founded this boxing style who went by the same name? I believe these are one and the same.

Wang, as with many famous generals in Chinese history, was deified. He became a god especially to those villagers and communities in the region near his birth. There is even a statue of Wang Lang located in Shandong province. There is however no mention in historical records of Wang Lang practicing or teaching something known as - praying mantis boxing. Wang existed long before mantis boxing appeared in the second half of the Qing dynasty. So how did Wang become the progenitor of this style in the 18th or more likely, the 19th century? Who incorporated Wang Lang into the mantis lineage, and why?

Was it Wang Rong Sheng (王榮生, 1854-1926) founder of the ‘seven star’ branch of praying mantis boxing? Even though Rongsheng had a different teacher (Li San Jian, also not a mantis boxer) than the other mantis boxers under Liang Xuexiang? Wang Rongsheng’s shared surname with the famous deity is likely a mere coincidence. Perhaps Wang Rongsheng’s family lineage tree did trace all the way back to the Han dynasty warlord. This is all conjecture. It is unknown who tied Wang Lang to Tanglangquan's history, but the time period can be narrowed down by other cultural factors which existed in Shandong province in the late 19th century, and from these a reasonable explanation of how this connection was made can be discerned.

Shen Quan

During the 1800’s boxers were highly prevalent in Shandong. Some were tied to religious sects, and mini uprisings, others to banditry. Most just trying to survive. Some were even recruited at times to fight the religious groups such as The White Lotus, and other sects. Foreign imports, and factories took many of the jobs in the cotton weaving industry Shandong was known for. A large portion of the population became unemployed, and economically depressed. Treaty ports such as Yantai (where mantis boxing was born), were affected even more by this foreign incursion of industry and lifestyle. This by proxy, caused a rise in banditry.

A mid-Qing (1700’s) emergence of Shen Quan (Spirit Boxing) in Shandong, whereby the practitioners recited incantations, danced wildly, and believed they had been possessed by a spirit/god that gave them courage, and even invulnerability, reappeared in the late 1800’s as the Boxer Uprising was beginning in full. The original founder of Shen Quan believed he had been possessed by a famous Tang dynasty general he knew from an opera. This same spirit-boxing was repopularized in Shandong during the late Qing when the region was collapsing economically and had been pummeled by droughts, famines, drug addiction, banditry, wars, and rebellions. A perhaps misguided means of ‘self’ control by villagers and peasants to pray for rain, or turn their deities ire toward their Manchu rulers, and later the western invaders.

At this time opera and folklore was highly popularized in local villages, towns. Famous stories were acted out such as Water Margin, Journey to the West, The Enfeoffment of the Gods, and The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Wang Lang’s exploits were part of these tales, and Wang was a hero that would have had personal meaning to the locals of Shandong as he hailed from their homeland.

Joseph W. Esherick explains:

“most north China villages had a small temple to the local God (Tu-di shen), or perhaps to Guan Gong.”

Additionally, Esherick writes:

“There was one paramount occasion when these temples became a focus for community activity: the temple fair, held annually at temples in larger villages or market towns. The name for these - “inviting the gods to a performance” (ying-shen sai hui). The center of attention was an opera, for the benefits of the gods.”

It important to capture this in the entirety of what Esherick writes next:

“Above all, these occasions were welcomed for the relief they provided from the dull monotony of peasant toil. Relatives would gather from surrounding villages. Booths would be set up to sell food and drink, and provide for gambling. The crowds and opera created an air of excitement welcome to all. But the statement of community identity provided by opera and temple was also extremely important. It is important, too, that the gods were not only part of the audience: many of the most popular dramatic characters---borrowed from novels which blended history and fantasy---had also found places in the popular religious pantheon. Since few villages had resident priests, and few peasants received religious instruction at larger urban temples, it was principally these operas that provided substantive images for a Chinese peasant’s religious universe. This is why sectarian borrowing from popular theatre is so important. To the extent that sectarian groups incorporated gods of the theatre, they brought themselves into the religious community of the village---rather than setting themselves apart as a separate congregation of the elect.

The importance of village opera for an understanding of the Boxer origins can hardly be overstated. As we shall see below, the gods by which the Boxers were possessed were all borrowed from these operas. That many of the possessing gods were military figures is hardly accidental. From what little we know of the operas of west Shandong, it is clear that those with martial themes, for example those based on novels Water Margin, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and The Efeoffment of the Gods were particularly popular. This is to be expected given the popularity of the martial arts in the area, but it no doubt helped that Jiang Zi-ya (Jiang Taigong), the hero-general sent down from heaven to assist the founder of the Zhou dynasty in The Efeoffment of the Gods, was himself supposedly enfeoffed in the north Shandong state of Qi, and the heroes of Water Margin made their base in the western part of the province.

In many ways it was the social drama of the theatre which tied together elements of popular culture most relevant to the rise of the Boxers. Here was the affirmation of the community which the Boxers sought to protect. Here were the martial heroes who expressed and embodied the values of the young martial artists of this region. Here were the gods by which the Boxers were possessed---gods now shared by sectarians and non-sectarians alike. When the young boxers were possessed by these gods, they acted out their battles for righteousness and honor just as surely as did the performers on the stage.”

Was Wang Rong Sheng spirit boxing with the deity Wang Lang? Was it one of his friends, Jiang, Song, or Hao, the founders of the other branches of mantis boxing (plum blossom praying mantis boxing, supreme ultimate praying mantis boxing, supreme ultimate plum blossom praying mantis boxing) that emerged around this time? All of them acting together perhaps? Or was this something their teacher Liang Xuexiang being wiser, older, educated, and well traveled used to inspire the younger boxers under his charge?

Esherick continues”

“The martial artists that we have seen in the mid-Qing (Li Bingxiao for example) were men whose social world was outside the village community. Many led wandering lives as salt smugglers, peddlers, or professional escorts; others were primarily associated with the gambling and petty crime of market towns.”

Later in the Qing, Escherick points out, this changed as banditry became more prevalent. At this time young men were more often studying martial arts for self-defense, and protecting their communities and families. There was a movement toward community defensive efforts, and in more agrarian areas, crop defense.

Whatever the reasons for Wang Lang being assigned attributions as the creator of praying mantis boxing we can most likely determine from the popularity of spirit boxing and the trend in the late 1800’s that this period in time during the late Qing, when shen-quan was revitalized, was the period when Wang was incorporated into the lineage. We can view this same occurrence in Eagle Claw Boxing around the same time period to the northwest in Hebei province. Yue Fei, another famous general in Chinese history is credited with founding that style. Yue Fei also had no definitive connection to eagle claw boxing prior to this time period in the Qing.

In the second generation of the lineage charts in both mantis boxing and eagle claw, are similarly obscured. In both styles there is no definitive link between the founder and the next verified carrier of the torch. The two have very similar discrepancies within their histories after these deities supposedly invented them. The oral records claim the styles after being invented, then went into the Shaolin temple almost 900km (560 miles) to the west, and three to four weeks walking distance away from Yantai where mantis existed centuries later. There is no known record of mantis, or eagle claw styles being part of the Shaolin boxing system. Are we to believe these styles, if they did exist at Shaolin for a time, were suddenly spit back out hundreds of years later back in Shandong or Hebei?

It is much more plausible that these military legends, Yue Fei, and Wang Lang, were brought about into these styles in the late Qing as spirit boxing rose to prominence once more amongst the martial artists of the time. As we’ll see in the time period of Li Bingxiao (李炳霄 1731-1813 estimated), during the ‘High Qing’, martial artists did not stay with one teacher. They rather learned from a multitude of sources similar to a modern day university student, thus making it extremely difficult for the concept of ‘styles’ to gain root during this time unlike a few decades later.

This can explain the lack of history in between the founders, and the verifiable practitioners of these arts in the late Qing. Why they suddenly ‘disappear’ into temples in their lineage charts. Only to then reappear centuries later with traceable roots. It explains an oral history in mantis boxing that this style was an amalgamation of 18 different ‘styles’. This is far more believable and easier to comprehend in the realm of martial arts if each of these 18 ‘styles’ was a technique or two from each independent source the practitioner learned from. Finally, it can further explain why prior to the 18th and 19th century, there is no definable lineage for these arts.

Bibliography

Esherick, Joseph W. The Origins of the Boxer Uprising. University of California Press, 1987

ChinaKnowledge.de An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art, edited by Ulrich Theobald - Sanguozhi 三國志(www.chinaknowledge.de), Wang Lang 王朗(www.chinaknowledge.de)

Luo, Guanzhong (14th century). Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Yanyi)

You can purchase these books on my Amazon store and help fund research like this.

The Origins of the Boxer Uprising - https://amzn.to/3c3iz36

Romance of the Three Kingdoms vol. 1 - https://amzn.to/2McZZKT

Romance of the Three Kingdoms vol. 2 - https://amzn.to/3sOIZM0

Romance of the Three Kingdoms vol. 3 - https://amzn.to/3sW5wXl

To Dissect a Mantis - A Summarized Re-Written History of Mantis Boxing

The following takes all of the data laid out from my timeline research (people, places, events, catastrophes, wars, rebellions, etc), as well as the mantis family tree, and assembles it into a condensed re-write of a more grounded history for mantis boxing. This is a brief overview notating some discoveries and answering questions, as there were many. For the purposes here, I removed mythical backstories and unsubstantiated people. Beginning instead with verified living representatives/associates.

The following takes all of the data collected this past winter from my timeline research (people, places, events, catastrophes, wars, rebellions, etc), as well as the mantis family tree, and assembles it into a condensed re-write of a more grounded history for mantis boxing. This is a brief overview notating some discoveries and answering questions…there were many. For the purposes here I removed mythical backstories and unsubstantiated people. Beginning instead with verified living representatives/associates.

Chinese soldiers 1899 1901 - Leipzig Illustrierte Zeitung 1900 [Public domain]

Here are a few of the questions I hoped to answer in my research on Praying Mantis Boxing.

The records are foggy prior to the 1800’s on the history of Mantis Boxing. Did mantis exist prior to this period?

If so, why did the 4th generation, fresh out of catastrophe on an epic scale in the late 1800’s, and the Boxer Uprisings that followed, suddenly start branding vanilla Mantis Boxing with other names such as - Plum Blossom, Supreme Ultimate, Seven Star? Other Chinese boxing arts of the region/time period did not see this same anomaly yet it was prevalent in Yantai. Did this ‘branding’ happen with the 5th generation of boxers in the first half of the 20th century?

Why are the forms inconsistent with each line of Mantis? If the forms existed as part of Liang Xuexiang’s art, why then did the next generation of boxers change them? If so, then why for the next century, were practitioners so meticulous about keeping these forms intact with little to no disruption?

Why was Li San Jian credited as a Praying Mantis Boxer when there is no evidence that he ever practiced the ‘style’?

Why did Li’s descendant, Wang Rong Sheng, who, by using dates and events, could not have learned Mantis from Li San Jian, but instead clearly learned mantis boxing from his friends - Jiang, Song, Hao, (‘students’ of Liang Xuexiang), end up as a major representative of the mantis style? Especially when he did not have the pedigree the other’s shared?

There is a recognizable crossover with meihuaquan in tanglangquan. What is the significance of the plum blossom symbolism and the prevalence with its use? Is there a link to meihuaquan? This style was spreading through marketplaces in the northern provinces leading up to the Boxer Uprisings, were the mantis boxers in Yantai connected with the uprisings? This creates more questions as the meihuaquan society was adamantly opposed to the violence and attacks on soldiers, missionaries, civilians, and property, such as churches and railways.

According to records, Jiang created and named a form in honor of the boxers connected with the rebellion - ‘Righteous and Harmonious Fist’. Was Jiang connected to the Boxer Uprising? Or was he simply angry at western encroachment and abuses like many in Shandong during this time?

Why is 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing so different from the other lines?

Begin…

A man by the name of Li Bingxiao (李秉霄, 1713-1813), becomes known for his fighting skills in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. He supposedly uses technique(s) that hook with two hands. As he gets older, he’s nicknamed - ‘2 hooks, Li’, or ‘2nd Elder of the Hook’. There is scant evidence of his backstory, but what has been carried down the lineage tree, is suspiciously close to the Confucius origin story. Confucius being highly revered in China for centuries, and originating in the same province - Shandong. Borrowing origin stories is a common phenomenon. Li allegedly teaches a student named Zhao Zhu.

Note: 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing Segway

At this point there is an oral note in the lineage charts that Wei San (De Lin), the accredited founder of the 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing line, met and sparred with Li Bingxiao.

“They could not best one another, but Wei San took some of Li Bingxiao’s methods.”

Thus begins the historical record of 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing. Wei San’s background was in liuhequan (6 Harmony Boxing), aka xingyiquan. The oldest form in this line of mantis is known as ‘duan chui’ - referred to in English as ‘short strikes’, but more appropriately it means - ‘to hammer a weak point, or to beat a weak point or fault with one’s fists’. This form is known to be the creation of Wei San’s student Lin Shichun, who was a bodyguard for the Ding family for a large portion of his career.

Note: This form is quite possibly the oldest representation of xingyiquan in a form.]

This form, known as ‘short strikes’, is the only form in this line at the time and has zero mantis hooks within. Something the practitioners of this line seem well aware of as it varies significantly from their other forms. However, it does share much of its striking and power generation with xingyiquan. I will continue this further down as we get to the branching out of mantis.

Resume…

Zhao Zhu (1764-1847), becomes a teacher himself. He allegedly teaches his sons, and a student named Liang Xuexiang (1810-1895) as Liang grows up. Liang goes on to serve in the military, and becomes a famous biaoshi (security-escort master) & boxer; one with a reputation and record that makes him a well known fighter in his province. His nickname is ‘iron fist’.

Li Bingxiao’s, and then Zhao’s techniques are passed on from Liang Xuexiang’s hands, including his own influences, to a new generation (4th) of boxers that includes his son. With the exception of his son, the teaching of many of his students takes place while Liang is in his late 60’s during a major famine preceded by 3 years of drought. Deathtoll - 9.5 to 13 million people died in the region during this 3 to 6 year time period.

At the time of joining Liang, all of these men were reported to be accomplished proficient fighters before meeting their ‘teacher’. Given Liang’s age and the surrounding events, this student/teacher relation appears to be more indicative of a mentor/client relationship. Liang possibly showing them some of his techniques, but their presence being more in line with protecting him and his family in his old age during extremely violent times.

His counterpart, Li Sanjian, did the same with his two students when visiting a friend in Yantai during this same period of unrest in Shandong province. It would make sense that an elderly, seasoned biaoshi (escort master) entering a foreign city in a time of catastrophe, would also be seeking out young, competent fighters to bring into his stable. Li’s students? Wang Rongsheng, and Hao Shunchang,

Note: Li Sanjian was credited with starting the line known as Seven Star Praying Mantis Boxing. Most people are now in agreement that this is false, and a way for Wang Rong Sheng to pay respect to his teacher, a branding advantage, or otherwise. Li never did mantis boxing, and while it is possible he knew, or knew of Liang, there is no indication he learned mantis from Liang, and was a more famous fighter by all accounts than Liang.

Liang Xuexiang, and Li Sanjian were both renowned escort-masters that ran dart bureaus ( biaoju ) in their lifetime. While they were likely still quite capable at defending themselves, it seems more plausible that they saw the writing on the wall in violent and chaotic times, and circled the wagons so to speak. Calling on younger, more capable fighters to assist them.

These fighters would benefit immensely from this relationship as well. It would after all, be an honor to claim either of these famous veterans as one’s teacher. The younger generation benefiting from this arrangement as much as the old.

The fighters under Liang Xuexiang, if they learned techniques from him, would then add Liang’s techniques (these hooking methods) to their own fighting skills. Each of these men could reasonably be considered rough and tumble fighters since they have each gone through multiple ‘mass droughts/famines’, rebellions, and grew up in a region full of strife. Their home province of Shandong has a reputation in China for producing tough, hardy people, especially boxers. It is a significant region in the history of the nation, where rebellions, bandits, invasions, and catastrophe have all left their mark.

The 4th Generation prior to ‘Mantis’

Style Notes:

Luohanquan, or Arhat Boxing, is a term developed in the early nineteen hundreds by boxers of the time attempting to revise history and accredit their martial arts to Bhudda. Stripping this away, it points to a general ‘Chinese boxing’ style of the Qing era that comprised of many common techniques that were not particular to any one ‘style’. Without the ability to label them, anything not clearly defined, usually gets called luohanquan.

Changquan, or Long fist is a more modern term used to classify the large body of ‘styles’, or more appropriately, boxing methods of the northern Chinese provinces. This can include lesser known styles as well as techniques shared in Hong Quan, Meihuaquan, Tongbei, Tanglang, Ying Zhua, Taijiquan, etc.

Hou Quan, or Monkey Boxing, is by all accounts one of the older ‘systems’ in the north. As evidenced by mention of it in Qi Jiguang’s book, in which he takes survey of the local martial arts in 1560 during the Ming dynasty. 300 years prior to the lives of these boxers.

Ditang, or Ground Boxing, is still alive in Shandong to this day. Evidence is lacking from General Qi’s book on the existence of ditang during the Ming, but it is apparent that it predates, or at the least runs concurrent with mantis boxing.

Liuhequan (6 Harmony Boxing), aka xingyiquan is a style born from the Muslim population in northern China and eventually adopted by the Dai family as the fighting methods for their biaoju company, and the guards under their employ. This is relevant to mantis boxing as it is the primary influence behind the 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing line.

The following styles are accredited to each of these mantis boxers prior to their association with tanglangquan.

Jiang Hualong - luohanquan, hou quan (monkey boxing)

Song Zide - luohanquan, hou quan (monkey boxing)

Hao Lianru - luohanquan

Sun Yuanchang - ?

Wang Rongsheng - changquan (long fist) + ditang quan (Ground Boxing) + whatever Li Sanjian taught him. Although that relationship was similar to Liang and his disciples.

Ding Zicheng - luohanquan (family art), xingyiquan/liuhe.

Four of the above mentioned fighters all opened schools post Boxer Rebellion. One of these boxers, Wang Rongsheng, goes on to teach two people privately. A disciple named Fan Xudong (silk merchant), and Wang’s own son. Prior to this, or during, Wang became good friends with Liang’s disciples, and at this time they shared knowledge with one another. Eventually all adopting the common banner of ‘Praying Mantis Boxing’. Each of them have all survived harrowing times up until this point.

6 Harmony Praying Mantis continued…

It is not until the 3rd generation of the 6 Harmony line (and 5th with the main mantis line), that ‘mantis hooks’ show up in 6 Harmony. Also accompanied by more forms. Ding Zicheng grew up under the tutelage of Lin Shichun. Learning Ding’s methods/bodyguard techniques. As we travel into the 20th century, Ding becomes good friends with one of Jiang Hualong’s students - Cao Zuohou, a 5th generation mantis boxing practitioner, now branded as plum blossom style mantis.

Ding and Cao, go on to share students with one another and cross pollinate. It is noted in their records that their followers could come and go to either school. This period is where we begin to see the additional 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing forms. Post Boxer Uprisings and well into the ‘martial arts for physical education’ stage of Chinese history.

Resume Main Line…

Each one of Liang Xuexiang’s students, as well as Wang Rong Sheng, goes on to brand their own version of mantis (seven star, plum blossom, and supreme ultimate). This draws into question the legitimacy of the existence of a ‘praying mantis boxing’ prior to this generation.

Evidenced by the simple fact that the only commonality among all of their arts are the following:

Forms with shared names.

The move known as ‘mantis catches cicada’ (engarde with hooks). Which appears to be nothing more complex than ‘branding/marketing’.

And the hooking techniques - seize leg, twisting hook, piercing hooks, lifting hook.

Nothing listed above is unique per se. The hooking techniques, absent the extra, and highly impractical curled fingers, all exist in Shuai Jiao records. Perhaps these methods were unique to this area at the time, exclusive in the setups to initiate the moves, or the follow-ups to the technique if the move is countered. The last being of particular interest to other fighters as is found in modern fighting arts.

The forms vary from each line at this point, or perhaps were mutated in the generation(s) to follow.

Note: Assuming the style existed prior to these boxers, or more specifically the forms of mantis boxing, and the methods of the mantis were Liang Xuexiang’s and his teachers before him; why would these boxers take it upon themselves to change these forms? Practitioners since then, have been incredibly adept at keeping these forms intact for the past 100+ years. Why would all of these boxers alter them?

Without supporting evidence to the contrary, it is difficult to accept that the name Praying Mantis Boxing existed prior to this point in history. It appears more likely that it was created by these 4th generation boxers/friends in the early 1900’s post Boxer Uprising, well after Liang Xuexiang, and Li Sanjian are deceased.

Did these younger boxers/friends brand their stuff ‘mantis boxing’ as a group? Was it based on the techniques from Li Bingxiao they now have in common with one another?

This would explain how:

They each have different names of their mantis style. Each able to keep an individual identity because they all had their own techniques unique to themselves prior to incorporating these ‘mantis’ techniques of Li Bingxiao on down. We end up with labels to signify the differences of each boxer prior to intercepting mantis - seven star, supreme ultimate, plum blossom.

It perhaps explains why the forms are inconsistent in each line. Shared in name only, but beyond that never having more than 2 lineages with consistent forms to one another. If the forms were handed down for generations prior, they would be sacred and undisturbed, not changed by Jiang, Hao, and Wang.

Liuhe tanglangquan (6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing) is a good example of this. The second generation of 6 harmony style (Lin Shichun) created a form known as Duan Chui (the only form prior to the 4th generation. Duan Chui still exists to this day, relatively undisturbed. Practitioners of all other lines of mantis since this period, have been obsessively adept at keeping these forms well intact with minimal changes. This makes it all the more improbable that the 4th generation would all of a sudden change the forms as they saw fit. Unless…there were no forms prior to this time…or forms were considered insignificant and not revered as they often are today.This would explain how, and why, Li Sanjian receives an honorary accreditation for a style he never did. It wasn’t a ‘style’ at all. It was a handful of techniques that Wang Rongshengs’ friends showed him. Wang never studied with Liang Xuexiang, as evidenced by the fact that he took the mantis moniker yet still claimed Li Sanjian (a non-mantis boxer) as his teacher.

If Wang had studied with Liang, and then changed his forms without giving proper credit, it would be incredibly disrespectful, and dishonorable. His ‘friends’ would certainly take issue with this. Instead, if it were simply a handful of methods from Liang that were passed down, it would make it easy to blend in with the other things Wang already knew and learned. Wang keeps his ‘teacher’ because there is no pure ‘line’ of mantis boxing to be loyal to prior to this.This also identifies why one of Wang Rong Sheng’s descendents was selected to represent ‘mantis’ in Jin Wu. Wang wasn’t ‘true mantis’ under the ‘Li Bingxiao -> Zhao Zhu -> Liang Xuexiang line’. So why would one of his students be picked to represent the mantis style for such a major endeavor in the south such a Jing Wu? If it really mattered that is? Why not one of the ‘true heirs’ - Jiang, Song, Sun, or Hao’s students? These boxers even had schools at the time, and Wang was only teaching one non-family member.

Lastly, this would explain why it was so easy for a 3rd generation descendant of Liuhe/xingyiquan to blend ‘mantis techniques’ that he learned from a 5th gen mantis practitioner, with his style of liuhequan. Combining a few techniques using the foundation taught to him by Lin Shichun, Ding Zhicheng wasn’t learning an extensive ‘system’, merely some techniques unique to these mantis boxers at the time. But certainly not unique in all of China, or the world.

What about the forms?

The forms could not have mattered. They obviously were not cemented in place. They were certainly not sacred if they were so freely altered. The techniques within these ‘sacred sets’ were common to other ‘styles’ of Chinese boxing, and Shuai Jiao in the region during that period of the Qing dynasty.

The curled finger mantis hooks expressed within the forms, are not necessary for the techniques to work. They all too often confuse observers/practitioners on the true martial intent of the move. If anything, they prevent the actual moves from working properly due to aesthetic stylization being placed above practicality.

What about the keywords? Aren’t they unique? Do they not define it as ‘mantis’?

No. I no longer believe this to be the case. These words are also part of the common boxing vernacular of the time. They offered nothing unique that isn’t found in Cotton Boxing and other fighter’s systems. Evidence by a few of the 12 keywords, and a plethora of techniques being shared with taijiquan. The mantis keywords that are not primary taijiquan principles, are listed in other subtexts as supplemental to the primary 13 keywords of taijiquan. A comparison can be found here in this working document Praying Mantis Boxing vs. Supreme Ultimate Boxing.

In Summation

As we would find in Brazilian jiu-jitsu today, with someone using the infamous ‘spider guard’ synonymous to that style - in mantis we have Li Bingxiao using his ‘double hooks’, aka - mantis controls/takedowns that caused him to stand out from the crowd of other boxers. Giving him an edge.

His methods were only allowed to exist as a ‘style’, because of a unique set of circumstances in history. Occurring at the end of an era of combat for survival, and the beginning of an era of wuxia, and physical education for profit.

Having seen and studied a wide range of Chinese boxing forms, provides me with a unique vantage point to be able to compare forms from various Chinese boxing systems north and south. The following are the moves I have found to be unique to ‘mantis forms’ that I have not seen in the other styles (this does not mean they do not exist. My knowledge/experience is certainly no where near all encompassing):

Seize leg (one variation)

Wicked knee

Hanging Hooks

Twisting Hooks

Pierce hooks (Edit: I later realized this is a shared application with one of the moves in Yang taijiquan’s - snake creeps down)

Possibly the ‘kicking legs’ methods are also unique.

All of the above methods are easily shared with competent experienced fighters/martial artists. Simple, easy to grasp methods. Akin to what fighters would be learning from one another, rather than convoluted systems of 70, 80, or 100’s of techniques/moves.

If we take each ‘boxing set’ at face value as a fighter’s ‘system’, consider for a moment how unlikely it would be to collect those in times of chaotic strife...

----

Arriving full circle -

We need not be bogged down by the chains of the past - politics, lineage, forms, etc. Take the best, discard the rest.

What is Mantis Boxing? An arsenal of hands, elbows; knees, kicks; throws and locks from Chinese boxing. We have the keywords to define it, and learn by. We have the roots. We honor them in our practice and continuation of the art.

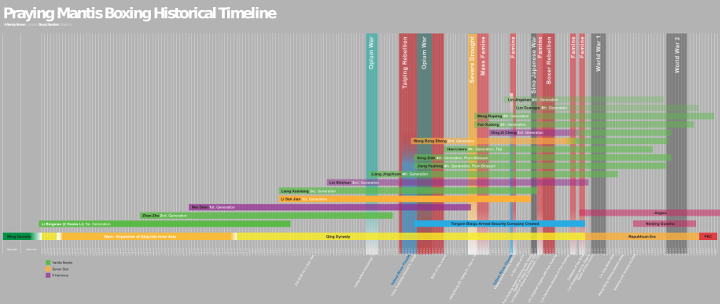

Mantis Boxing Historical Timeline - Qing Dynasty to Republican Era

A true Mantis Boxing Historical Timeline from the Qing dynasty to the Republican Era. This tool was pivotal in drawing conclusions in my research on the history of Praying Mantis Boxing. Months of investigation culminated and presented in this beautiful chart designed by Bruce Sanders. Now available for your own research or enjoyment.

Collapse and Fall Into Ruin - (Beng 崩)

A huge thanks to Gene Ching and the team at Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine for publishing my article this month. Such an awesome presentation! Thank you to my team - Holly Cyr, Vincent Tseng, Max Kotchouro, Bruce Sanders, and Sean Fraser for your assistance in making this happen. I am honored.

A huge thanks to Gene Ching and the team at Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine for publishing my article this month. Such an awesome presentation! Thank you to my team - Holly Cyr, Vincent Tseng, Max Kotchouro, Bruce Sanders, and Sean Fraser for your assistance in making this happen. I am honored.

The article is an expose on the Mantis Boxing principle of Beng (Crush, or to Collapse and Fall Into Ruin). You can read the rest of the article 'Collapse and Fall Into Ruin' in the July/Aug issue on store shelves now, or available online.

The Dirty History of Tai Chi

The history of Tai Chi, correctly called Tai Ji Quan, disseminated to the masses, is often a mythical story that involves an art form thousands of years old with Taoist immortals, monks, and fairies. Commonly it is propagated that a non-existent type of magical energy, will heal the practitioners body and/or throw opponents without ever touching them. This is a fictional portrayal that in the West we call a fairy tale and in the East they call wu xia.

The history of Tai Chi (taijiquan, supreme ultimate boxing) is often taken with too much salt. The prevalent history disseminated to the masses often involves a mythical backstory thousands of years old, which includes: Taoist immortals, monks, and fairies. It is commonly propagated that the style of Tai Chi contains and revolves around a type of magical energy (known as qi) that will heal the practitioners body and/or throw opponents, without ever touching them. This fictional portrayal in the west would be known as a fairy tale, in China it is called ‘wǔ xiá’ (武侠), martial arts stories in theater/fiction popularized during early 1900’s China.

The notion that one can achieve unequivocal power, something akin to a superhero, without ever performing a day of ‘rigorous’ training, exertion, or hard work, is certainly the stuff of movies, myth, and legend. In contrast, the truth of tai chi’s history is far less enchanting to the laymen dabbling in an exotic art. The truth involves laborious acts, physical exercise, redundant practice, mental endurance, self-discipline, perseverance, and a history full of bloodshed, violence, and oppression.

General Qi Jiguang. Source: Wikimedia

The more accurate and verifiable history at the time of this writing shows that tai chi was developed roughly 400 years ago in Chen Village, Henan Province, China. It was known as less formally as ‘Cannon Boxing’, or the Chen family style. Like many Chinese martial arts it included hand-to-hand combat techniques common to the region, area, and time period. In 1560, General Qi Jiguang developed an unarmed combat system to train a militia to fight the wokou pirates. A group of Japanese pirates, which included Chinese ex-soldiers, privateers, and ruffians were pillaging the coastal villages and sea traffic. Based on the chapter in Qi Jiguang’s manual on unarmed combat, and the included illustrations, it appears by the trained eye that many of the depicted hand-to-hand combat methods are found in what is now known as tai chi. This points to a common pool of knowledge of fighting techniques.

During the mid 1800's Yang style tai chi was created by founder Yang Lu Chan. Yang, lived and studied in Chen Village and later went on to create his own system originally called 'Small Cotton Boxing'. Now known as Yang style tai chi, or taijiquan.

While many of Yang’s techniques mirror the Chen family boxing style, Yang included some of his own methods and merged them with the techniques of the Chen style, as any fighter will do throughout their martial journey when introduced to effective combat methods that they wish to amalgamate into their own art.

Yang’s life (1799 - 1872), or the life around him, was no stranger to violence and upheaval. Throughout his adult life he bore witness, knowingly, or unknowingly, to the impending collapse of China’s final dynasty, the Qing (1636-1912). Events happening all around Yang during his life include catastrophic flooding of the Yellow River (Huang He) (1851 - 1855, and many many more), famines, droughts, drug epidemics, two wars with the west (see Opium Wars 1839-1842, and 1856-1860), multiple rebellions (see Nian rebellion 1851-1868 and Taiping rebellion 1850-1864), and the encroachment of western powers on the Chinese populace, especially in and around trade ports.

As a result of losing both of the aforementioned wars, China was forced through treaty to pay reparations to the western powers, mainly by opening previously closed trade ports in the south and the north.

Imperial Standard of the Qing Emporer

Yang Lu Chan at one point in his life is recorded as being hired by the Qing court to teach armed, and unarmed combat to the imperial guards of the Manchu court in Beijing. Yang also disseminated his boxing art to his family.

Around the turn of the 20th century, decades after Yang’s death, the Chinese became disenchanted with their martial arts after repeated embarrassment in their confrontations with the west. More specifically incidents involving armed and unarmed combatants known as boxers, versus soldiers with firearms. Arguably the most famous of these incidents is known as the 'Boxer Rebellion', or more accurately the ‘Boxer Uprising’ (Joseph W. Esherick - The Boxer Uprising), which transpired over a four year time period with various encounters. The uprisings took place in Shandong, Hebei, and Tianjin provinces, as well as Beijing itself.

Port of Chefoo circa 1878 to 1880. Edward Bangs Drew family album of photographs of China, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Historical Photographs of China - https://hpcbristol.net/visual/Hv37-02

A century prior to this China was one of the most powerful civilizations on earth, with one of the most formidable military forces in existence. However, the industrial age in the west brought substantial change to warfare, along with the ability for nations to project global power in greater magnitude than ever before.

Although martial arts was considered beneath the scholar class, it was prevalent with boxers, soldiers, and guards in the employ of biaoju (security-escort companies). Local militia-men, sanctioned by magistrates commonly used armed/unarmed martial arts methods to quell local bandits and keep the peace. The Qing government in the 1800’s was preoccupied and impotent to respond to many smaller internal issues. The lowest expression of martial arts was associated with criminals, gangsters, ruffians, or charlatans which the Jing Wu and early 1900’s Chinese martial arts community tried to erase, or reverse.

The ‘boxers vs firearm’, or rather, antiquated military tactics versus modernized, industrialized weapons and strategies incidents that took place around 1900, likely further cemented the general public’s poor opinion of their nations martial arts, and of the ‘boxer’ overall. Three hundred years prior during the Ming dynasty General Qi, in his second book, published two decades after the first and post wokou battles experience, considered the act of training troops in hand-to-hand combat a rather fruitless endeavor when compared to the rapid and effective weapons training such a spears and matchlocks. This is evident since his second book omitted the unarmed combat chapter altogether.

Battle of Lafang 1900. Source: https://pin.it/5uubzq3xry77n5, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By the turn of the 18th to 19th century the Chinese having battled the western power’s sponsored opium crisis, repeated mass famines, floods, droughts that killed millions of people; rebellions that also killed millions more, and in addition to disease epidemics, were being called the 'sick men of Asia' by the international community. For a culture that was once in the not to distant past, more powerful than any other nation on earth this was humiliation on an epic scale.

At the end of the Qing (1910’s) and the beginning of the Republican era, a movement was initiated to change this stigma. A nationalist effort was undertaken to strengthen the populace and remove this cultural blight, or poor reputation. As a part of this movement and perhaps in an effort to keep their national arts from dying, Chinese martial arts teachers were commissioned to teach their methods for health, strengthening, and fitness, rather than for fighting.

This saw the creation of organizations such as the Jing Wu Athletics Association (circa 1910) of which tai chi, specifically Yang style, was a significant part of, as well as later the Nanjing Central Guoshu Institute in 1928. The directive of Jing Wu was primarily to improve health, and combat the 'sick men of Asia' label. Teaching physical fitness and health to affect positive national change. The Nanjing Guoshu Institute also propagated Chinese martial arts, and employed none other than Yang Chengfu, grandson to the progenitor of the style.

Yang Cheng Fu clearly had an entrepreneurial spirit that would help proliferate not only the Yang family art, but by proxy their predecessor, the Chen family, as well as the Yang offshoots of Wu family style Taijiquan, and Wu Hao style. Yang Chengfu took his grandfathers boxing art and taught far and wide, spreading it to the general public for health and wellness purposes around 1911.

Chengfu incorporated slow motion practice and longer movements as the focal point, removing much of the fighting application and combative elements taught by his grandfather, father, brother, and uncle. Thus was born a form of exercise that was all at once accessible to the young, old, weak, sick, and those of poor physical condition; to which rigorous exercise was not possible.

Prior to this Yang family taijiquan was taught strictly for combat, or a method of violence, or rather, defending against violence. It involved such skills as striking, throws, trips, takedowns, joint locks, sparring, fighting, and weapons training.

Forms practice (tào lù 套路), and push hands (tuī shǒu 推手) in contrast to present day, were likely a very small portion of the training. It is questionable if push hands had a significant role in the traditional combative training outside of skill building. It is possible that this portion of the training was derivative of the scholar class slumming in the martial arts world years after the art lost its teeth. A ‘game’ for people uninterested in fighting to pretend they are fighting.

It is also possible that given the heavy focus of the Manchu on wrestling, which was significant with the Han as well, that push hands was a tool for training wrestling skills in said competitions. The strategy of pushing an enemy in battle is ludicrous unless pushing them to the ground, or off a cliff. However, pushing someone outside a ring, or off a platform (lei tai matches) in order to score points, or win, holds a great deal of validity.

Qianlong Emporer observing wrestling match. Source: WikiCommons

Due to Yang Chengfu's efforts, and others around him, Yang style went on to become extremely popular, the most widely proliferated form of taijiquan throughout the world even to this day. The style’s true nature however is evident by some writers of the time:

Gu Liuxin writes of Yang Shaohou (Yang Cheng Fu’s older brother 1862-1930)

He used, “a high frame with lively steps, movements gathered up small, alternating between fast and slow, hard and crisp fajin (power/energy), with sudden shouts, eyes glaring brightly, flashing like lightning, a cold smile and cunning expression. There were sounds of “heng and ha”, and an intimidating demeanor. The special characteristics of Shaohou’s art were: using soft to overcome hard, utilization of sticking and following, victorious fajin, and utilization of shaking pushes. Among his hand methods were: knocking, pecking, grasping and rending, dividing tendons, breaking bones, attacking vital points, closing off, pressing the pulse, interrupting the pulse. His methods of moving energy were: sticking/following, shaking, and connecting.”

1949 Taiyuan battle finished. Source: WikiCommons

Three decades after Chengfu’s popular introduction of this rebranded art to the people, the Communist Party took control of China. As in past rebellions and changeovers of power, they once again outlawed the instruction of martial arts for the purposes of fighting. Mao Zedong, ever a student of history was well aware of the number of uprisings, rebellions, and dynastic turnovers associated with temples, and boxers. He burned the temples and banned the boxers.

During this period in the mid twentieth century, many traditional martial artists fled the country or were killed. The restriction by the government was certainly not in fear of a boxer, spearman, or swordsman attacking a tank, or machine gun nest, but rather due to a need to control the populace, a task exponentially more difficult when it involves submitting those trained in fighting arts (disenfranchised privateers, aka pirates). Martial training empowers individuals and empowered people are less willing to blindly succumb to oppression.

In 1958 after the period of unrest during the Communist Revolution (circa 1946 to 1949), China formed a committee of martial arts teachers. Choosing from a pool of those who stayed behind and used their martial arts training for coaching health/fitness, and/or those who had returned to the mainland from their exile.

The committee created what are known as the ‘standardized wushu sets’ - choreographed forms of shadow boxing summarizing and abbreviating the broad spectrum of China's legacy martial arts styles.

The wushu committee created the standardized sets for unarmed and armed styles, streamlining hundreds of styles in the north, and south that shared common techniques into one compulsory set to represent each - long fist (changquan) for the north, and southern fist (nanquan) for the south. In this consolidation effort, a few styles were left to stand alone gaining independent representation. These were, praying mantis boxing (tanglangquan), eagle claw boxing (yingzhaoquan), form intent boxing (xingyiquan), 8 trigrams boxing (baguaquan), and supreme ultimate boxing (taijiquan). Coincidentally these five styles were the advanced curriculae of the Jing Wu athletic association. Had they not been part of Jing Wu, it would be interesting to know if they would have survive long enough to be recognized by the PRC Wushu Committee.

These choreographed sets were then presented to the rest of world in a neat clean package, government regulated, and used to project China’s human martial prowess abroad, to include a trip to the Nixon White House where they demonstrated their skills. These boxing sets left behind the fighting elements of old, replacing them with sharp anatomical lines, clean corners, fancy acrobatics, and gymnastics. They became martial dance with 'timed' routines rather than the violent methods they once were.

As part of this standardization process in the 1950’s, the Yang taijiquan 24 movement form (a.k.a. Beijing Short Form) was created, and not by the Yang family itself oddly enough. This form represented Yang Style taijiquan (against the families approval) and went on to not only be a competition set, but a ‘national exercise’ that Chinese citizens would practice every morning in local parks for decades to come.

As China opened her doors to the rest of the world, westerners glimpsed the large organized gatherings of Chinese citizens performing their beautiful practice of the short form in parks day after day. Foreigners began learning this art while spending time overseas and via teachers who migrated to western countries proliferating their ‘art’ through hobby, or as a means of financial survival. The western world's interest was officially piqued.

Throughout the 1960's-70's and even into the 1980's, there may have existed a reluctance with Chinese teachers to show ‘outsiders’ their national, or personal martial arts, but others did not know the original intent of the art, and continued to spread the empty shell they were handed.

These factors helped contribute to the spread of misinformation, making it difficult to validate much of the material being practiced outside of the ‘standardized’ sets. The Chinese fighting arts were also fast approaching a century of existence without the practical combat usage of the fighting techniques housed inside the forms being transmitted as part of the art.

Without the trial by fire checks and balances that a martial fighting system uses to hold its validity; such as - 'fail to do this technique correctly and you get punched in the face, tossed on your head, or pushed off a platform' - an environment was effectuated that was ripe for esoteric practices, myth, and legend to take over. To include, but not limited to; mysticism, numerology, archaic medicine, fancy legends, mystical energy, and the most contagious of them all…pseudo-science.

While the combat effectiveness waned, the health benefits of modern taijiquan remain steadfast and clear. There have been many studies by qualified medical professionals around the world substantiating the health benefits of routine tai chi practice in one’s daily activities. However, these health benefits are not unique to tai chi, and may be attained through most almost any form of physical exercise such as, but not exclusive to - running, swimming, cycling, dance, tennis, raquetball, and numerous other sports.

There remains though, a primary advantage of tai chi over some, but by no means all other forms of exercise. A low-impact form of physical exercise accessible to those unable to perform rigorous exercise. This is especially important to senior citizens, or those with debilitating injuries who can benefit from movement, but are unable to participate in high impact sports mentioned above.

Modern tai chi, while no longer a martial art is a form of exercise or martial dance, that can be taught to people of all ages, allowing practitioners to move, think, and have fun as a social activity anywhere they go. Whether it be those looking to improve balance, circulation, stress reduction, bone strength, or those who think they are too old to work out, or too “out of shape” - all can find a welcome home in studying the soft styles of tai chi in its modern representation.

Conversely, if one is looking for a martial art for the purposes of practicing and perfecting methods of violence in its traditional sense, then the modern representations of tai chi, or taijiquan are likely not to be pursued.

What we can all stand to discard, are the esoteric pseudo-science methods transmitted by charlatans and those looking to manipulate others for financial gain, or illusions of power.

LEARN MORE…

If you enjoyed this article you may also find the following articles of interest -

Personal Quest

Alongside teaching tai chi movement for well over a decade, my thirst for the combat applications of these moves/forms overshadowed my ability to teach people without discussing, showing, demonstrating, and instructing people in the combat methods inside the tai chi forms as I unraveled them.

I realized, my goals and desires were no longer aligned with the middle aged, and senior audience that was partaking in my classes for the benefit of health and wellness. Rather than cause injury to people who were, intrigued, but not committed, conditioned, or enrolled for such a class, I amalgamated these combat methods into my mantis boxing classes so I could continue to teach them to a captive audience who is there for such knowledge and skill, and would like to put these into practice for their skill set.

While I retired from teaching tai chi for health and fitness in 2016, I remained steadfast in my quest to unlock these combat applications lost to the annals of time. If you would like a small glimpse of the results of decades of work in reverse engineering these amazing combat techniques that are half a century old, check out the following page to see videos of a few of the moves.

Tai Chi Underground - Project: Combat Methods

Bibliography

Wile, Douglas. T'ai-chi's Ancestors: The Making of an Internal Martial Art. New York: Sweet Ch'i, 1999. Print.

Kennedy, Brian, and Elizabeth Guo. Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic, 2005. Print.

Wile, Douglas. Lost Tʻai-chi Classics from the Late Chʻing Dynasty. Albany: State University of New York, 1996. Print.

Kang, Gewu. The Spring and Autumn of Chinese Martial Arts, 5000 Years = [Zhongguo Wu Shu Chun Qiu]. Santa Cruz, CA: Plum Pub., 1995. Print.

Smith, Robert W. Chinese Boxing: Masters and Methods. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1974. Print.

Fu, Zhongwen, and Louis Swaim. Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Berkeley, CA: Frog/Blue Snake, 2006. Print.