Research Notes (Open): Power Building Boxing (功力拳, Gōng Lì Quán)

Gōng Lì Quán is a unique boxing set from northern China that is found included as a training routine amongst a variety of boxing styles in the north, to include, long fist, eagle claw boxing, and praying mantis boxing. It likely mixed with the latter two styles when it was included as….

Gōng Lì Quán, or Power Building Boxing is a unique boxing set from northern China. It is included as a training routine amongst a variety of boxing styles in the north to include: long fist, eagle claw boxing, and praying mantis boxing. This form likely intermixed with the latter two styles when it was included as part of the Jīngwǔ Athletic Association’s fundamental wu shu curriculum.

At Jīngwǔ, gōngliquán was one of six mandatory ‘empty hand’, and four ‘weapon’ sets taught to practitioners. These ten sets were required as a prerequisite to the study of other styles of Chinese boxing: xingyiquan, bagua, taijiquan, eagle claw, or mantis boxing; considered by Jīngwǔ founders to be more ‘advanced’ styles.

MY FIRST INTRODUCTION

I first came across gōnglìquán whilst studying Eagle Claw Boxing back in 1999/2000. Although it often is, Gōnglìquán was not included in the style of mantis boxing I was learning at the time, but it was my introduction to Eagle Claw Boxing. This was the first version of the set I learned.

The research I’ve done on this set over the years has predominantly been focused on the physical execution of the movements, the variations of the boxing set from one style to the next, and the combat applications of the movements within the set.

Back in 2006 I delved deeper into gōnglìquán with the intent to reverse engineer the combat applications. Gōnglìquán was passed on to me as an empty shell, a form of shadow boxing or choreographed series of movements, as was most of my early Chinese boxing.

At the time that I first attempted to figure out the secrets hidden within the set, I lacked the knowledge and skill to properly dissect it, my expertise at the time was rooted in striking, kicking, and submissions (qin na), not wrestling, or grappling.

In attempting an analysis of this set however, I learned eight different versions, comparing and contrasting each set with one another with the goal of keeping the redundancies, while eliminating anomalous moves that were likely performance based rather than combative.

We set about at translating a couple of books on gōnglìquán, with one of my students Adria Kyne handling the linguistics, Adria could speak and read Mandarin so her expertise was invaluable. Since most of the text was written in ryhme, or verse, relevant to one ‘in the know’, these translations were sadly of little benefit in unlocking the true intent behind these moves at the time. As years passed I kept practicing and teaching the set up until a final seminar I taught in 2012.

TRIM THE FAT

Since 2012, I’ve rarely turned an inkling of a glance in the direction of gōnglìquán. I no longer train or teach forms, my time is consumed with fighting application and sparring which I find much more rewarding and a far superior vehicle for teaching the arts to others. Gōnglìquán became a distraction from my work on mantis boxing sets, keywords, and taijiquan combat applications so I left it on the side of the road while I traveled on.

However, a recent discussion began weeks back in a pub in Wales, UK between another high level Chinese boxer and myself as we bombastically tossed one another around the bar sharing techniques. The conversation has continued since via back and forth emails, and as such has brought my attention back to this boxing set I left behind so long ago.

Our didactic discourse has included many subjects in the field of Chinese boxing, but repeatedly returned to the element of Chinese wrestling transmitted within these boxing sets. If a reader is not yet aware of the level of influence folk wrestling has had on the formation of these boxing sets passed down for over a century, then you are in for an amazing discovery.

THE WANDERING WARRIOR

During the pandemic, Vincent Tseng (Black Belt - Mantis Boxing) began his deep dive into gōnglìquán while he was locked down in Taiwan and studying Shuia Jiao there. Vincent reached out to me at the time on his rekindled interest in the set, and we discussed the high probability of the set being wrestling-centric. I supported his endeavors and Vincent went to work on forming his own analysis of gōnglìquán that you can find on his YouTube channel — The Wandering Warrior.

While Vincent and I did converse on his project at the time, and he graciously shared his videos with me, which I thought were excellent, I was in full on survival mode at the time trying to keep our team training remote, building online courses, streaming classes, and meeting everyone’s needs, while at the same time rehabbing our derelict house. My attention to Vincent’s work while committed and sincere, was short lived. At the time I was also tearing apart (again) Beng Bu and Luan JIe, two of the core boxing sets from mantis boxing and re-interpreting their techniques. My headspace for reverse engineering combat methods from forms was 100% devoted to these sets.

Since picking gōnglìquán back up for the reasons I’ll list next, I have specifically avoided revisiting Vincent’s extensive work with the purposes of avoiding any cross contamination of our different analyses. Once this project is complete I plan to go back and revisit Vincent’s work and compare commonalities to see where our interpretations intersect.

REKINDLED INTEREST

My new friend Graham Barlow of The Taichi Notebook has a background in Xingyiquan, Taijiquan, and Choy Li Fut, a southern style of Chinese martial arts, as well as a black belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Thus we can speak seamlessly on Chinese martial arts, BJJ, and grappling/wrestling. In one of his styles, Choy Li Fut, there is what some practitioners refer to as choy li fut’s ‘signature move’: sau choy. A similar move to this is found inside gōng lì quán, what we call 3 Rings Trap Moon. As Graham and I talked I took another look at the set with the knowledge and eyes I have now. Some new and intriguing ideas on the combat applications came to light, and it would appear the entire set consists of wrestling moves, which is counter to any translation I or others have attempted in the past.

It is important to remember that sets like this were a vehicle or storehouse for a boxer’s system of moves. Many boxers of old spent a bulk of their practice time alone. The set’s name translates as: power building boxing. One practicing the set uses the movements within to train the creator’s boxing techniques in a manner akin to exercise, a creative way to transmit the movements to others without reading and writing; skills which were rare at the time. The use of hyper low stances, calisthenics, exaggerated movements, and dynamic tension, allow for a self contained training system alongside a library of techniques.

Below are videos with one of my black belts Tom McNair. We began with shooting a couple of videos (Double Bump, or Punch, and Three Rings Trap Moon) to highlight the ‘stylized’ shadow boxing move juxtaposed with the ‘weaponized’ combat application. Enjoy.

UPDATE: Since starting this mini project, it would appear another daemon has decided to drop by my dojo for summer break. I’ve been unable to turn my attention away from the set and keep unmasking the combat applications previously hidden before my eyes. So for the meantime, at least until this welcome, but uninvited guest leaves town, we’ll be releasing more of these videos, possibly the entire boxing set. This weekend I’ll be adding Twining Silk Legs, Lock Neck Through Sky, and Pluck Eggplant.

Stay Hooked!

Gōng Lì Quán Videos

Tyrant King Lifts Ritual Tripod | Throw in Well

Coming soon…

Horse Dragon Deep Sea

Coming Soon…

Collide Elbows, Double Bump

Twining Silk Legs

Lock Neck Through Sky

a.k.a. — Sweeping Moon Off The Wind Over Clouds, and Overturn Sack. This move is executed with slight variations from version to version. Here we depict Lock Neck Through Sky and Overturn Sack variations.

Cast Off Hand/Capture Hand

Next Up. Stay Hooked!

Pluck Eggplant

This move is another counter to the counter when committing to 3 Rings Trap Moon attacks. Rather than stepping back, the opponent steps around the leg to maintain position.

Three Rings Trap Moon

Make Coil Squeeze Pound/Lock Neck Carry On Head

Up Next. Stay Hooked!

Slant Chop aka Single Whip

Up next. Stay Hooked!

Gōng Lì Quán Boxing Set Demonstration (Tao Lu) - 2012

Gōng Lì Quán Boxing Method

Tyrant King Lifts the Ritual Tripod

Letter Hand Throw in Well

Bow Stance Horizontal Fist

Horse Dragon Deep Sea

Letter Hand Throw in Well

Horse Dragon Deep Sea

Double Cross Waist

Double Bump (L)

Collide Elbows, Double Bump (R)

Lock Neck Through Sky

Twining Silk Leg (L)

Twining Silk Leg (R)

Collide Fist

Cast-off Hand

Pluck Eggplant

Collide Fist

Cast-off Hand

Three Rings Trap the Moon (R)

Three Rings Trap the Moon (L)

Three Rings Trap the Moon (R)

Three Rings Trap the Moon (L)

Collide Elbows, Double Bump (L)

Collide Elbows, Double Bump (R)

Collide Elbows, Double Bump (L)

Cast off Hand

Capture Hand, Collide Fist, End Cast-off Hand

Make Coil Squeeze Pound

Lock Neck Carry On Head

Cast-off Hand, Collide Fist

Capture Hand, Collide, Fist

Slant Chop Fist

Jump step, Clap Palm, Collide Fist

Pierce Palm

Servant Stance Navel Eyebrow Palm

Pierce Palm

Collide Fist

Translating ‘Fist’ (Quán 拳)

As Chad Eisner points out in his translation of Qi Jiguang’s treatise on unarmed combat found on Judkin’s Kung Fu Tea blog, the character ‘Quan’ 拳 is used in various ways, especially when discussing Chinese martial arts. At times it is used as ‘fist’ and at other times as ‘boxing’. When used in conjunction with other characters such as in this case Gōng 功 and Lì 力, it more specifically refers to a system of “unarmed techniques/combat” which denotes anything from striking to kicking to grappling or wrestling techniques. It is not confined to punching.

Gōng Lì Quán Grappling ‘System’ Breakdown

The following is a breakdown of the moves within the choreographed set, categorized by technique types found within the Gōng Lì Quán ‘system’. I now refer to it as a system after discovering the inclusion of: ji ben gong training (fundamentals), grip defense, combined with the series of throwing/tripping/sweeping methods embodied in the form. Gōng Lì Quán by all indications is a self-contained training system for the creators’ grappling/wrestling methods.

“When our only tool is a hammer, every problem is a nail.”

Any instances of what appears as a strike or a kick found within the set, can be dismissed with almost complete certainty as being a punch or a kick. These techniques used in such a manner would prove to be disastrous in a real fight.

Upon deeper examination of the set through the lens of grappling methods common to the region, each move can be explained and shown to be effective wrestling methods. Many of these techniques still exist in shuai jiao as well as other wrestling arts found in China and surrounding cultures.

Grips, Grip Defense, & Jibengong

These are techniques centered on deflection, parrying, blocking grip attempts, and/or breaks.

Tyrant King Lifts the Ritual Tripod

Letter Hand Throw in Well

Bow Stance Horizontal Fist

Horse Dragon Deep Sea

Double Cross Waist

Cast off hand

Capture hand

Throws, Trips, Sweeps

Collide Elbows, Double Bump

Lock Neck Through Sky

Twining Silk Legs

Collide Fist

Pluck Eggplant

Three Rings Trap Moon

Lock Neck Carry On Head

Slant Chop

TBC…

Gōng Lì Quán Historical Record

Anyone with more information on the roots of Gōng Lì Quán is welcome to email me, or leave a comment below. Your contributions will be greatly appreciated and added to the post with accreditation.

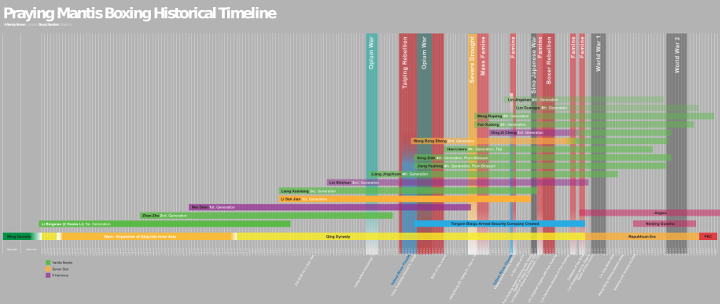

While little in the way of solid facts exist around Gōng Lì Quán’s origin prior to Jing Wu, there are numerous oral sources naming Cangzhou, Hebei as the place of origin. Some sources claim it arrived on the scene early in the Qing dynasty, but this is uncorroborated. Of note is, Cangzhou being central to Baoding and Tianjin, both major Chinese wrestling centers throughout several dynastic periods in China’s history.

The Taiping Institute lists over 33 styles of empty hand and weapon sets they claim originate from Cangzhou. Gōng Lì Quán being among them. There are no sources listed for these attributions so it is difficult to know if this is revisionist history, or if Cangzhou is actually home to a large number of Chinese martial arts ‘styles’ that have survived till modern times; if survival includes the empty shells known as forms (tao lu).

NATIONAL STRENGTHENING & REFORMATION

As is well documented at this point in martial arts scholarship much of modern Chinese martial arts was changed, morphed, and re-appropriated from fighting to physical education as part of the nationalist efforts of the government of China in the early twentieth century, with the goal to strengthen her populace after repeated humiliations with the west — lost wars with western and eastern powers, corruption, disasters, famines, rebellions, and drug epidemics.

Amongst these efforts was the creation of institutes chartered with the task above, and modeled after and in direct competition with the YMCA. Jing Wu was one of these institutions. At the inception of Jing Wu they included a revamped Chinese martial arts as part of the curriculum, alongside many other sports and activities with the express goal of physical education.

Tasked with establishing a curriculum to represent the nation’s martial arts, and attempting to consolidate over 100 or 100’s of styles, it is my view that they initiated a ‘culling of styles' in an effort to represent this diverse kingdom in a manageable way. Many of these styles: red boxing (hongquan), plum boxing (meihuaquan), ba ji, power boxing (gongliquan), etc etc etc) contain a common vernacular of movements, making a strong case for why they were excluded.

If a style did not stand out as 'unique', or have a strong brand or history already attached to it (mantis, eagle, bagua, xingyi, taiji), it is easy to believe it was chopped up for parts. Whereby similar movements found to overlap other styles tossed into a larger bucket of ‘Northern Shaolin Long Fist’, or an overly simplified North/South context. Simplifying a convoluted and confusing history that was not relevant to the government's purposes, or in line with the mission at large.

Fast forward to the 1950s and this categorization was further propagated and reinforced by the PRC when they created modern Wushu and the creation of standardized sets (forms) being bundled into long fist and southern fist. It is plausible to see why gōnglìquán, a set from Cangzhou, if the oral accounts are to be believed, with large extended movements similar to other longfist-style movements, was included alongside other styles from the north. Add to this that gōnglìquán does not have a significant number of unique techniques, roughly sixteen moves, making it even easier to include it in a broader system, especially when some of these same moves are found in taijiquan, tanglangquan, and yingzhouquan.

EMPTY SHELL WRESTLING

By the time of Jing Wu’s creation it is possible the fighting applications of the techniques within gōnglìquán had already been lost to time making the boxing set even less distinguishable from other routines.

Of interest is, Jing Wu had a wrestling program independent of these basic wushu routines. This leads me to further believe that the combat methods of gōnglìquán were already lost, although it is possible it varied enough from the wrestling curriculum that whoever dictated that program’s training regimen had a distinct bias for an altogether different style of Chinese wrestling. The intriguing question is: if the combat methods inside the form were still known, why would a fighting form full of wrestling moves from Cangzhou, be taught without…the wrestling?

PERSONAL PROJECTION

If one throws out all of the included evidence that points to gōnglìquán being comprised of wrestling moves rather than strikes and kicks, and disagrees with the video demonstrations above, if gōnglìquán truly is not wrestling, meaning that I am only projecting my own knowledge, experience, and research onto this set with revisionist intent, then we have an incredibly strong argument that this set would fall under the experiences of General Qi Jiguang and other author’s survey of Chinese boxing styles during the Ming dynasty -

“These flowery styles had lost the foundation of boxing and strayed very far from some presumably simple and original form.“

The reason being, none of these techniques stand up to battle testing in a boxing and kicking context. A bevy of examples found in books, videos, YouTube, over the past 30 years or more, demonstrate these moves being applied as such. Each and every example under careful scrutiny fails to stand up as effective in real fighting vs fantasy boxing, or kung fu movie fighting.

Anyone using these techniques as strikes and kicks will meet with utter failure even against novice street fighters or strongmen, never mind seasoned fighters and grapplers from other styles even within regional borders, and across the globe.

NORTHERN SHAOLIN MYTHOLOGY

In modern writings gōnglìquán is categorized as being a “Northern Shaolin”, and/or “Long Fist (chang quan)” boxing set. It is more likely that this inclusion amongst Shaolin is part of the overarching oversimplified duality of Shaolin versus Wudang, or Northern styles versus Southern styles classified early in the twentieth century and later reinforced by the People’s Republic of China in the mid twentieth century.

The Shaolin Temple is 416 miles (617km) SW of Cangzhou. Essentially equivalent to a trek from Boston, Massachusetts to Washington D.C. There is a significant distance between these areas. Although it is too easy to assume zero to low probability of boxing and wrestling pollination between such great distances in the 1800s. Reflexively we think of things in modern day settings where a majority of us would never dream of walking 416 miles to get to a destination. We think of travel in terms of automobiles, trains, and planes, failing to recognize that humans have been far more migratory as a species for thousands and thousands of years, and the 1800’s was well traveled.

China is no exception. It is impossible to rule out that someone from Shaolin traveled to Cangzhou and disseminated their martial knowledge there. However, Shaolin was not known by us for wrestling, gōnglìquán is not recorded as being taught at Shaolin, and Cangzhou has both wrestling, and gōnglìquán as part of its heritage. Peter Lorge in his book Chinese Martial Arts From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century dispels the excessive credit and significance of Shaolin’s influence on China’s martial arts history as a whole, citing a 900 year gap in Shaolin even being mentioned in regards to martial arts, and only reappearing in the Ming dynasty when they help battle pirates — with weapons.

Lorge goes on to elaborate that the connection between Shaolin and martial arts was becoming more prevalent during the Ming. Lorge also makes clear that the focus of these martial arts was predominantly based on weapon combat rather than unarmed, as weapons were more effective at defending Shaolin’s lands and assets. Furthermore, he points to temples such as Shaolin being refuge for travelers on their journeys, where it would be more likely techniques were brought here, or learned here during someone’s stay.

We can conclude that while not improbable for someone of the time to travel to pick up fighting methods and disseminate those in another region hundreds of miles away, the gōnglìquán Shaolin origin falls apart when we compare the histories and styles of both areas, look at the types and methods of combat being transmitted in each, and fail to have any substantial evidence of gōnglìquán existing at Shaolin, not even oral records.

Jīngwǔ

Jīngwǔ was created in 1910 as part of a national reformation movement. This was another attempt at using Chinese martial arts to help combat a weakened populace and culture. Chinese martial arts were not viewed highly prior to this, in part due to the humiliating defeat of the boxers vs the western powers during the Boxer Uprising. Chinese martial arts was often tied to nefarious groups with less than noble intentions. This is an oversimplification of an intricate and complex problem with many tendrils attached. The purposes here are not to rehash the history of Jīngwǔ, or the Boxer Uprisings, but to trace gōngliquán’s path to modern times. I’ll end my commentary on the wider implications with another quote from Ben Judkins:

“This basic social pattern started to undergo a fundamental shift in the wake of the Boxer Uprising (1899-1901). In the modern era (dominated by firearms) the original military applications of the martial arts started to look outdated to a number of educated social elites. Actual military and police personnel had reasons to continue to be interested in unarmed defense, but these sorts of concerns rarely bothered arm-chair reformers or “May 4th” radicals. In fact, many of these reformers and modernizers wanted to do away with traditional hand combat. To them boxing was an embarrassing relic of China’s feudal and superstitious past.

For the martial arts to succeed in the 20th century they would need to transition. They had to be made appealing to increasingly educated and modern middle-class individuals living in urban areas. It would be hard to imagine a group more different from the rural farm youths that had traditionally practiced these arts. But this is the task that the early martial reformers of the 20th century dedicated themselves to.”

NOTE: If a reader is interested in a deeper understanding of the time period where Chinese martial arts transformed from a fighting art to a form of physical education, commercialization, and a coupling with more esoteric and religious practices, I highly recommend reading Joseph Esherick’s ‘The Boxer Uprisings’ for a better understanding of the late 1800’s into early 1900’s China. For extensive detail on what would become The Republican Era, and the Nanjing Era, I recommend the plethora of articles written by Ben Judkins in his prolific blog Kung Fu Tea. The references at the end house several sources that can satisfy your thirst for knowledge.

Jīngwǔ had a large charter when it came to fitness, Chinese martial arts was only a part of it. The YMCA is truly the best comparison as a member could take up tennis, fencing, wrestling, etc etc etc. When it came to martial arts though, Jīngwǔ had a basic curriculum and then an advanced track. The martial arts were taught as forms (taolu) and combatives/sparring were not the focus. The goal was fitness and exercise.

Their directive was noted in an English article published in the Jīngwǔ 10th anniversary journal:

“Ten years ago [1909] when the Association was founded, the press and the general public criticized and called it a place for breeding “boxers.” The gentlemen interested, however, were not discouraged, knowing the need of physical culture for the 400 million and the value of “kung fu” as gymnastics.”

Gōngliquán was one of six mandatory ‘empty hand’, and four ‘weapon’ sets taught to practitioners before they could advance. These ten sets were required as a prerequisite to the study of other styles of Chinese boxing: xingyiquan, bagua, taijiquan, eagle claw, and mantis boxing; considered by Jīngwǔ founders to be more ‘advanced’ styles.

When assembling the curriculum for Jīngwǔ, Judkin’s writes:

“the institutional structure of the modernist Jingwu Association tended to absorb sets from various arts rather than presenting them as distinct, self-contained, lineages.”

While I am still searching for more information on the curriculum development for the martial arts program at Jīngwǔ, and specifically why each set was chosen, we can see that gōngliquán was obviously chosen, and did not have a Shaolin heritage that was necessarily tied to it. Nor was it the purpose of Jīngwǔ to promote this narrative as seen in Tse’s writing about Ying Hon Lan’s research, and Andrew Morris’ book on this period:

“Yin details how the martial arts were at their lowest ebb during the 1900s due to successive failures on the battlefield, the Boxer Rebellion, and the elimination of the Imperial martial examination in 1901.17 From this low point, Yin describes how martial arts became a sport discipline in schools and in the standing armies of various warlords by the 1910s and 1920s.

This work is one the first to draw extensively from the primary sources within the Republican Era Guoshu Periodicals Collection. Yin uses a variety of primary sources to recreate the rich martial arts milieu in Republican China, while the roles of martial arts as a form of physical exercise (as promoted by the Chin Woo Athletic Association) have also been covered in Andrew Morris’s Marrow of a Nation.”

Performing a quick internet search of ‘Shaolin gongliquan’ finds a plethora of martial arts schools claiming the set to be Shaolin while coincidentally reproducing the exact or near simulacra of the basic curriculum of Jing Wu established in Shanghai in the summer of 1910. This attribution to Shaolin or longfist is extremely tainted, and is by all appearances being revised onto Shaolin, not by Jing Wu, but rather the later division of Chinese boxing into Northern & Southern styles established by the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Guoshu Institute in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s.

Modern kung fu practitioners continue this cycle of syncretism by selling a story of a wrestling set from Cangzhou with no connection to Shaolin or longfist (changquan), as being an art that is now Shaolin, or ‘northern long fist’, while presenting absolutely zero evidence of this being true. Simply a regurgitation of a narrative built 100 years ago to suit the purposes of a government organization of the time.

The inclusion of the above historical detail on Jīngwǔ is important to our purposes as it establishes the official written record of when gōngliquán appears on record, how it connects to other styles such as eagle claw and mantis boxing, and the critical aspect of — Chinese martial arts at-large, but specifically the forms found in Jīngwǔ, no longer being taught with martial application included. Rather instead, strictly taught as exercise sport. With this established we can focus on how a style known as changquan came to be, and parse out if gōngliquán is, or is not, a part of this style.

CHANGQUAN (LONGFIST)

Longfist has a separate and congruent history alongside gōnglìquán, with some claims linking it back to Emperor Taizu of the Song dynasty (960-1279). General Qi Jiguang in his 1560 survey during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) mentions: “Taizu’s stances of the long fist”, but the reference is to ‘stances’ not a style, or even fist methods.

There is a bottomless void when it comes to searching out any real scholarship that has been done on the history of this style. In all likelihood this is due to it being fabricated as a ‘style’ in the early 1900’s as part of the reformation movement. Of note is that, a majority of the narrative is espoused by lineages linked to Han Qing Tang and the Nanqing Guoshu Institute which we’ll cover later on.

According to the changquan Wikipedia page the actual historical term can only be traced back to the second half of the 1800’s, coincidentally the same time other styles of boxing in China began to revise their histories and/or brand themselves. This is when we also see an explosion in the commercialization of Chinese martial arts. A quote from the wiki page points to this much later creation of longfist:

“The Long Fist of contemporary wǔshù draws on Chaquan, “flower fist” [sic meihuaquan], Huāquán, Pao Chui, and "red fist" (Hongquan)”.”

This helps make a case that the ‘long fist’ style was born out of the Nanqing Guoshu Institute and is not an ancient style that existed from the Song dynasty. It also explains why these other styles that are the formation of longfist, and popular in the Qing dynasty, disappeared or at the least, lost substantial popularity and flirted with extinction. Post Nanqing Guoshu Institute is when we see the shell of the northern Shaolin as a system arriving on scene, and gōnglìquán now included as a part of this style.

TAIZUQUAN

There is a style called Taizuquan which still exists today, but it lacks any mention of a set known as gōnglìquán while mentioning many others. A quick review of the wikipedia page on Taizuquan, summarizing the bare-hand sets in the style, shows an absence of gōnglìquán. There’s little point in this research to delve further into this style as it has no bearing on gōnglìquán.

SHAOLIN BURNING - THE CENTRAL GUOSHU INSTITUTE

The Nanqing Guoshu Institute is important in establishing when, where, and why I believe gōnglìquán ended up being classified as Northern Shaolin Longfist.

Albert Kayter Tse writes in the opening paragraph of his dissertation — Unfulfilled Potential: The Central Guoshu Institute in Republican China 1928-1948:

The Central Guoshu Institute 中央國術館 (1928-1948) in Nanjing was a martial arts entity funded by the Nationalist government to ‘promote better physical health to the population through martial arts practice.’ With its prestige and funding, the Central Guoshu Institute opened a nation-wide network of martial arts schools, held two national marital arts tournaments, published books and journals researching and preserving martial arts, participated in exhibition tours of Southeast Asia and the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, and trained a new generation of martial arts masters. In 1937, with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war, the Institute relocated several times before disbanding in 1948 on the eve of the Communist takeover.

1928 to 1938 is known as the ‘Nanjing decade’, a period in the Republican Era of China’s history. Before we go further let's establish a few facts:

1911 - Jingwu was created in 1911 in Shanghai and later opened a branch in Hong Kong. Gōnglìquán is included in the curriculum.

1927 - Shaolin temple burned.

1927 - 1950 - Chinese Civil War

1928 - Nanjing Guoshu Institute created. Later includes Shaolin styles in its curriculum. Gōnglìquán is not included in the curriculum of Nanjing Guoshu Institute.

1937 (technically 1931) to 1945 - Second Sin0-Japanese War, also known as World War II.

The Shaolin temple burned to the ground in 1927 under orders from Chiang Kai Shek, leader of, at the time, the National Revolutionary Army and after 1928 the leader of the Republic of China. The head abbott of the temple gave sanctuary to his friend, a rebel general fighting against Chiang’s Northern Expedition to reunite China. After losing he fled to the temple seeking refuge. According to records, when Chiang’s soldiers arrived to rout the general, the monks of the temple fought back, losing to superior firepower. Chiang’s general ordered the temple burned and Shaolin history and manuscripts were lost in this fire. (Yang Jwing-Ming, (2009, December) History of Shaolin Longfist)

Gōnglìquán was already included in the Jingwu curriculum 16 years prior to the Shaolin fire and 17 years prior to the creation of the Guoshu Institute. There is no indication that Shaolin was connected to Jingwu.

The Nanqing Guoshu Institute was created in 1928 by General Zhang Zhiziang. In a biography of her father, Zhang Runsu wrote:

“The defining moment of how Zhang conceived of the plan for the Central Guoshu Institute is explained: while convalescing from an injury in 1926, the newly retired general used martial arts as a form of rehabilitation. During this time, he came to feel that the martial arts would be suitable for the entire Chinese populace.”

Once again we see that the focus of these institutions that heavily influenced modern Chinese martial arts, was anything but combat application, and they continued to propagate toothless tigers for ulterior purposes.

It is important to note that gōnglìquán was not included in the Nanjing Guoshu Institute curriculum as we can see below from Tse’s dissertation where he cites a 1933 recruitment article:

“in the Zhongyangribao 中央日報 on 9 December 1933 shows the numerous styles students were expected to master in three short years for the training programme”

Kicking methods

Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced, Tantui 彈腿Striking courses

(Xingyiquan 形意拳, Tai Chi Chuan 太極拳, Baguaquan 八卦拳, Bajiquan 八極拳, Chaquan 查拳, Xinwushu 新武術, Lianbuquan 練步拳, Zaquan 雜拳, Xingquan 行拳, Chuojiao 戳腳, Pigua 劈掛)Weapons courses

Double-edged sword: (Qingpingjian 青萍劍, Sancaijian 三才劍, Kunwujian 昆吾劍, Longxingjian 龍形劍, Houbeijian 猿臂劍)Single-edge sword: (Meihuadao 梅花刀, Baguadao 八卦刀, Maodao 苗刀, Yingzhandao 應戰刀, Piguadao 劈掛刀)

Pole: (Shaolingun 少林棍, Kunyanggun 群羊棍, Xinwushugun 新武術棍, Tongzigun 童子棍)

Spear: (Duanmenqiang 斷門槍, Daheqiang 大合槍, Suokouqiang 銷口槍)

Whip: (Taishibian 太師鞭)

Competition-based courses

(Sparring, Weapons, Wrestling, Boxing, Bayonet, Pijian 劈劍)Elective courses

(Mianquan zuoluohan 綿拳醉羅漢, Zuibaxian 醉八仙, Zuiquan 醉拳, Houquan 猴拳, Joint locking methods)Special courses

(Qigong 氣功, Tieshashou 鐵砂手, Hongshashou 紅砂手, Swimming, Sprinting, Baseball)Military courses

(Fundamentals of instructing, Combat instructing)

Of note from the figure above, is mention yet again of wrestling but with no specifics or names.

Nanjing Guoshu Institute lasted until 1938 when the Sino-Japanese War (World War II) came to China. Tse writes:

“During the Sino-Japanese War, the Central Guoshu Institute, reduced to a handful of staff members and students, relocated with the Nationalist government to the Chinese interior. Lacking official funding, the Central Guoshu Institute existed in name only until it was disbanded in 1948 on the eve of the Communist takeover.”

Here we see a gap in the transmission of knowledge from the Guoshu Institute in mainland China until the creation of the People’s Republic of China post World War II, and post Chinese Civil War. Given the inclusion of gōnglìquán in styles such as mantis and eagle claw we can see clearly that it was transmitted to these systems directly through Jing Wu.

Decades later we see gōnglìquán coupled with another form straight out of the Guoshu Institute called, lianbuquan (continuous boxing). Lianbuquan is a subject for a separate deep dive. What is important for our study is that the two of these forms show up in modern times under the moniker of Shaolin Longfist, but neither of them are Shaolin, nor Longfist in origin.

Was this related to the Shaolin vs Wudang narrative built by the Guoshu Institute? If so, why would the Guoshu Institute, a government sponsored institution, be inclined to then use Shaolin in its directives or branding, especially after the government burned it down?

SHAOLIN VS WUDANG – A TOXIC CHOICE AT THE GUOSHU INSTITUTE

At the inception of the Guoshu Institute Zhang Zhijiang started a classification of Chinese martial arts systems within the institute that resulted in an immediate and toxic battle that spans decades later into modern times. Tse writes:

“Courses began on 11 May 1928 with an initial intake of 70 to 80 students. Two departments handled the martial arts instruction: wudangmen, shaolinmen. During the early 20th century, Chinese martial arts were typically grouped into styles derived from the Wudang mountains, or from the Shaolin Monastery. The two martial arts sects were diametrically opposed: Wudang focused on internal cultivation, valued softness and was affiliated with Daoism; whereas Shaolin focused external cultivation, valued hardness, and was affiliated with Buddhism. The two departments were headed by two acclaimed masters: the Wudang section by Sun Lutang, and the Shaolin section by Wang Ziping.

It did not take long, however, before internal discord broke out. As the two sects were traditional rivals, the students of either department often clashed with each other in the fledgling institute.”

“The tension between the two departments reached a boiling point, with department heads and the teaching directors facing off against each other to see whether Wudang or Shaolin was superior. With the entire student body watching, Wang Ziping and Gao Zhendong fought fiercely, followed by the teaching directors fighting with bamboo spears. Wang, unhappy with being embroiled in this conflict, eventually resigned and returned to private life in Shanghai.”

This segregation and oversimplification of the rich and varied styles of Chinese boxing and their unique heritage was seared into the minds of those who attended the Guoshu Institute. The Republican Era is one of the most prolific periods for written material on the Chinese martial arts. Thus the impact of those who attended the institute, or were instructors there, who went on to write curriculum and instruction manuals propagated this idea of Shaolin vs Wudang, or Buddhist vs Taoist categorization. The ridiculousness of this is apparent when reading Judkins’ account of Meir Shahar’s book on Shaolin taking notice of Shaolin during the late Ming dynasty, and we find Shaolin at the time incorporating Taoist philosophy and medicine into their practices.

What is amazing to me is how impactful and permanent this became in the Chinese martial arts demographic. After the chaos it caused in the institute, they abolished the classification system by July of the same year, a mere two months after the doors opened.

“By July, the dual-department arrangements were abolished. The Central Guoshu Institute was rearranged into teaching, publishing, and general-affairs divisions.” (Tse)

Of note when permeating the details of the Guoshu Institute, is the fact that later instructors in the institute focused on Western Boxing and Chinese Wrestling for combat methods rather than homegrown martial arts systems. This is important as it shows that all of the other ‘striking’ styles in the institute with Chinese heritage - xingyiquan, taijiquan, baguaquan, bajiquan, chaquan, xinwushu, lianbuquan, zaquan, xingquan, chuojiao, pigua, were not being passed on with combat methods training, only forms training.

This is significant as it proves that by this period in Chinese martial arts history, when it comes to organizations like Jingwu and the Guoshu Institute which were responsible in large part for not only carrying on many of these styles, but elevating their fame and popularity post Chinese Civil War, the fighting application of each style was no longer being transmitted within the halls of these organizations. While it is difficult to ascertain with certainty exactly when such transmission stopped, we can at least see by this point that it is gone. Anyone passing on these systems from this point on, is transmitting empty shells of deceased fighting methods.

A few noteworthy quotes from Tse’s work highlight these points. The first of which is his recounting of the 1928 National Guoshu Examinations (a tournament) where people competed in Chinese weapons demonstrations as well as empty-hand demonstrations. These were non-contact and executed as choreographed routines known as forms or taolu. As we can see from the following quote, Chinese boxing was already dead at the Guoshu Institute:

“Second, of the top 15 examinees, three brothers Zhu Guofu (widely viewed as the winner), Zhu Guozhen, and Zhu Guolu won based on their sparring experience. Well versed in traditional arts (Xingyiquan, Shaolinquan, wrestling and Tai Chi), it was their ‘unofficial’ training in Western boxing which offered them the ability to train against resisting partners while attacking at full intensity with padded gloves.” (Tse, pg 35)

As we can see, when it came to sparring and combat, the participants relied on western boxing rather than their homegrown martial arts styles. The next quote emphasizes the purpose of the institute overall, and why this was acceptable to the government:

“By the late 1930s, the consensus model of physical education best suited for ‘saving the nation through physical exercise’ was a combination of Western military calisthenics, modern sport and guoshu. As such, the Central Sports College’s mandate exactly suited the needs of the times.” (Tse, pg 33)

The negative view of the Chinese boxers after the early 1900’s, plus a desire to modernize and incorporate more western practices to defeat the negative reputation of a weak China on the world stage, there was a gravitation to the western practices that were seen as superior to things beyond just Chinese martial arts. However, the martial arts suffered greatly as the early 20th century was the disintegration of combat application being handed down to the following generations. Much of which was henceforth passed on as empty shells for the next hundred years and more.

Was the labeling of these two sets as Shaolin Longfist even more recent than we think? Could they have been categorized as such after the PRC was born?

To be continued…

REFERENCES

Kennedy, B., & Guo, E. (2010). Jingwu. Blue Snake Books.

Peter Allan Lorge. (2012). Chinese martial arts : from antiquity to the twenty-first century. Cambridge University Press.

Tong Zhongyi. (2005). The Method of Chinese Wrestling. North Atlantic Books.

Reevaluating Jingwu: Would Bruce Lee have existed without it? (2012, August 15). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2012/08/15/reevaluating-jingwu-would-brucle-lee-have-existed-without-it

Cangzhou Martial Arts | 沧州武术 – Taiping Institute. (2024). Taipinginstitute.com. http://taipinginstitute.com/cangzhou-martial-arts

Qi Jiguang (1560/1580). Jixiao Xinshu 紀效新書 New Treatise on Military Efficiency.

Zhu, Jianliang. (2023). A Study on the Evolution of Chinese Wrestling, the Characteristics of the Project and Its Value. Global Sport Science. 1. 10.58195/gss.v1i1.36.

Graceffo, A. (2018). The Wrestler’s Dissertation.

Wikipedia Contributors. (2024, July 16). Changquan. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Changquan

Wikipedia Contributors. (2023, February 22). Taizuquan. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taizuquan#Taizuquan_Changquan

Bringing Northern Styles South: A Brief History of the Liangguang Guoshu Institute. (2018, December 13). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2018/12/13/bringing-northern-styles-south-a-brief-history-of-the-lianguang-guoshu-institute/

The Book Club: The Shaolin Monastery by Meir Shahar, Chapters 5-Conclusion: Unarmed Combat in the Ming and Qing dynasties. (2012, December 7). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2012/12/07/the-book-club-the-shaolin-monastery-by-meir-shahar-chapters-5-conclusion-the-evolution-of-unarmed-martial-arts-in-the-ming-and-qing-dynasties/

Martial Classics: The Complete Fist Canon in Verse. (2018, October 26). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2018/10/25/martial-classics-the-complete-fist-cannon-in-verse/

Tse, A. K. (2019). Unfulfilled Potential: The Central Guoshu Institute in Republican China 1928-1948 [PDF Unfulfilled Potential: The Central Guoshu Institute in Republican China 1928-1948].

Yang, J.-M. (2009, December 30). History of Shaolin Long Fist kung fu. YMAA. https://ymaa.com/articles/history-of-shaolin-long-fist-kung-fu

“Zhongyang guoshuguan she shifanban,” Zhongyang ribao (Nanjing), December 9, 1933.

Lives of Chinese Martial Artists (4): Sun Lutang and the Invention of the “Traditional” Chinese Martial Arts (Part I). (2020, December 17). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2020/12/16/lives-of-chinese-martial-artists-4-sun-lutang-and-the-invention-of-the-traditional-chinese-martial-arts-part-i-2/

Secondary References

Yin Honglan. Jindai zhongguo wushu de zhuanxing yanjiu Research on the Transformation of Contemporary Chinese Martial arts]. Shenyang: Dongbei daxue chubanshe, 2016.

Morris, Andrew D. Marrow of the Nation – A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Zhang Runsu, ed. Zhang Zhijiang zhuanlüe [A Short Biography of Zhang Zhijiang]. Shanghai: Xuelin chubanshe, 1994.

The Plum Blossom Connection To Mantis Boxing

Praying Mantis Boxing (táng láng quán 螳螂拳) upon closer inspection, has a deeply rooted past that is intersected and conjoined with the plum boxing. There are a multitude of references in names of mantis boxing sets, movements within forms, and even branches of the mantis boxing style that split off from the main line and went on to brand themselves more specifically as plum blossom praying mantis boxing. It goes beyond mere symbolism. To understand this we have to…

Symbolism

Plum Blossom - logo design - Randy Brown - 2006

The plum flower (méi huā 梅花) is a prolific symbol in Chinese culture. The flower is one of the very few blossoms to appear in the early spring when snow is still a possibility. There are countless images in Chinese art culture depicting the plum blossom emerging through snow covered branches. The symbolism of this particular flower is powerful, a metaphor for ‘strength through adversity’, or ‘overcoming hardship’.

Upon close inspection, Praying Mantis Boxing (táng láng quán 螳螂拳), a style from Shandong province in northern China, has a deeply rooted past that intersected and conjoined with plum boxing, another popular style of the time and region. There are a multitude of references found within names of mantis boxing sets, specific movements within forms, and even branches/lines of the mantis boxing style that split off from the main line, going on to brand themselves as ‘plum blossom’ praying mantis boxing. This goes beyond mere symbolism and speaks to something greater. To understand this we have to delve deeper into the region, politics, and time period where the style originated, and discuss another style of boxing known as, Plum Boxing.

Plum Flower Boxing

Plum Flower Boxing (méi huā quán 梅花拳), or méi quán, is a folk style of boxing from the border regions of Jiangsu, Anhui, Shandong, Henan, and Hebei province in northern China. It began during the Qing dynasty, and by the collapse of the Qing in the early 1900’s, it had thousands of followers; although this description is rife with technicalities.

For one, the word styles is in question. In the early and mid Qing dynasty boxers rarely stayed with one teacher for any significant length of time. ‘Styles’ as a construct were few and far between outside of family units. A boxer’s repertoire was an amalgamation of techniques from various teachers and counterparts across the north China plains. Joseph W. Esherick writes of this in his book on the origins of what is commonly known as the Boxer Rebellion, which he more aptly describes as a series of ‘uprisings’.

As we get to the late Qing, when plum boxing is gaining in popularity, we see more styles begin to take significant roles in the Yellow River region in the 1860’s. Esherick notes,

Boxing was particularly popular in this area - both as recreation for young men, and as a means of protecting one’s home in an increasingly unstable countryside.

He also quotes a Linqing gazeteer. They said,

The local people like to practice the martial arts — especially to the west of Linqing. There are many schools: Shaolin, Plum Flower and Greater and Lesser Hong Boxing. Their weapons are spears, swords, staff and mace. They specialize in one technique and compete with one another.

Shaolin boxing was tied to the ‘bandit-monks’ as Chinese historian Peter Lorge describes them. Temple monks hired local ruffians and bandits to protect their land holdings and crops. They were monks only in title and appearance, but more accurately put — armed enforcers for the temple.

Red Boxing (Hong Quan) was the preferred boxing methods of security guards, escort masters, and family bodyguards in the northern provinces. Albeit this was not the style of origin for a bodyguard who began the 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing line in the generations to follow.

Plum Flower Boxing has a variety of descriptions tied to it, all of them accurate in their own rights. The synopsis - a ‘style’ only in the loosest sense of the word. More accurately - a series of boxing methods used for self-defense, but more for exhibition in village marketplaces. It was named not for a style so much as the time of year these exhibitions normally took place — in early spring before the field work began. A period during which, spare time was more plentiful for the agrarian society, and the plum blossoms were appearing on the trees. The ‘plum boxers’ would arrive in the markets touting their skills. (Esherick, 1987)

Dr. Peter Lorge, a Chinese historian wrote

“many local styles [of Chinese martial arts] subsumed themselves under the rubric of Plum Blossom Boxing when it became famous [due to its association with the Boxer Rebellion] at the beginning of the twentieth century” (2012:208; see also Zhang and Green 2010)

Dr. Tom Green, and Dr. Zhang Guodong write extensively on the folk aspect of Mei Boxing in their research (Zhang and Green 2010) on the style, and its integration in local villages that survives even to today.

By the end of the 19th century plum boxing had thousands of practitioners. Shandong, the birthplace of mantis boxing, was replete with plum boxing practitioners, and the now known style was taught by one of the famous patriarchs and leader in the boxer uprisings - Zhao Sanduo. Esherick writes heavily on Zhao and his role with the rebellion. Ben Judkins follows up in great detail as well.

The significant point of immediate interest for our purposes, is to note the popularity of the style as well as its migratory nature. This was not simply limited to one small region in China. The style spread from village to village, city to city as the 1800’s progressed on towards the turn of the century. If we stick with the concept of styles being a construct of a series of techniques learned from multiple sources, or as Green puts it - “a common vernacular in the region”, then we can understand why one style or boxer, would absorb the methods of another so seamlessly. As with modern day martial arts, and the popularity of videos on fighting technique for almost any style you can think of - we practitioners seek out and use what works. Efficacy is at the forefront. This concept is not unique or exclusive to human beings in the 21st century, and it would be hubris to believe so. It would be especially present when dealing with violent and chaotic regions where your life and the life of your family depended on these skills, as existed during this time period.

The Collapsing Empire

Crane on a Snow-Laiden Plum Tree - ink on silk - Attributed to Lu Fu, second half of the 15th century -after 1505

There are questions as to the ‘true’ age of praying mantis boxing. For now we’ll assume that mantis boxing was an actual ‘style’ prior to the late 19th century.

Liang Xuexiang, the lineage holder in Shandong Province, China during the late Qing dynasty. Liang returned from Beijing in 1855 to his village in Laiyang county (Yushankuang) two days walk south of Yantai. At this time the region to the west of the village was in the fifth year of catastrophic flooding of the Yellow River. The Taiping Rebellion was raging in the south. The second Opium War, known as The Dart War would begin the following year in 1856.

Liang Xuexiang was a biaoshi (escort master) prior to retiring, and possibly a soldier in the Qing military (although I have yet to verify this with more than one source). I am told by another credible source that he was a silk merchant in Beijing prior to returning to his village. It is worthy of noting, according to Chircop-Reyes and his paper on Merchants, Brigands, and Escorts, a biaoshi was hired based on factors which included their martial arts lineage.

In 1875, Liang was in his mid 60’s when his life intersected with the next (4th) generation of mantis boxers. The boxers who would then go on to diverge the style from it’s core lineage, and propel it onto separate paths into the present day. Liang, with his experience as a biaoshi, may have been considered a village protector upon his return, or just passing the time in his later years teaching for fun.

During 1875, a majority of the Shandong province was gripped by severe drought that had begun two years prior in 1873, and was still ongoing. Four years of mass famine would follow this drought claiming the lives of 9.5 to 13 million people within five northern provinces of the north China plains which included Shandong. An estimated 8 to 12% of the population.

Opium was ravaging the populace, as well as continued western encroachment and pressure. Yantai was home to one of the treaty ports that was forced open by the western powers at the Treaty of Tianjin (1858) following the Dart War. The White Lotus Rebellion was off and on in the border regions of Shandong, and banditry was a significant problem in northwest and southwest of Shandong. Militias were growing in popularity to quell these threats.

The Qing rulers were meanwhile engrossed in fending off a multi-pronged attack on their rule from outside powers and internal rebellion, as well as corruption which all told, compromised their ability to maintain power. An economic fallout from the catastrophic floods, major rebellions fought in the south and the west that sapped their military strength; foreign powers beating down their door, and the eventual Japanese invasion during the Sino-Japanese war (1894-95). This invasion included battles in Shandong next door to Yantai, in Weihai Wei.

The Qing military at it’s apex was remarkably powerful and adept with the 8 banner armies of the Manchu. By this time however, they had become lazy and unkempt. The Green Banner army, comprised of Han Chinese, not Manchu bannermen, was now the leading force to deal with rebellions and fight off foreign incursions with any significant effect. The Qing military lacked technological advancement, and the western powers made short work of the Qing army in any altercation. Likewise, Japan during the Sino-Japanese war, sunk the much larger Chinese fleet in its entirety in a single day.

The intrusion of Catholic and Protestant missionaries, their willfulness at not only converting villagers, but influencing the political establishment, caused a growing resentment toward these religions, their leaders, and their followers alike. Thus was the climate of Shandong during the 1800’s as Plum Blossom Boxing spread, and mantis boxing was branded.

The rise of Méi Huā Quan

As mentioned, méi quan was the name of a growing martial art in northern China well before and during the lives of the 4th generation of mantis boxers that followed Liang Xuexiang. Liang is noted as training under Zhao Zhu, who trained under Li Bingxiao - known as ‘two hooks Li’, the likely progenitor of the mantis boxing lineage around the turn of the 19th century, if there was one. His existence is difficult to verify, and his name has questionable translations.

Those who would become the fourth generation of mantis boxers, to teach others, were the following: Liang Jingchuan (Liang’s son), Jiang Hualong, Song Zide, Sun Yuanchang, and Hao Lianru. They were all friends with one another in Yantai.

How were these boxers tied to Liang Xuexiang? They are claimed in the mantis oral records as being students of Liang. Upon deeper inspection though, this is a more difficult question to answer. At the time they met Liang they were the following ages: Hao was still a child at 11 years old. Jiang and Song were 20 years old; both had experience in other boxing styles prior to meeting and ‘training’ with Liang, according to their biographies.

Is it possible Jiang and Song, and the other boxers their age, were in Liang’s employ as escort guards rather than martial arts students? That is, if Liang was still operating as a security boss at this time. There is no known evidence of when Liang ended his service in this career so this is difficult to answer.

Another possibility is, they were bodyguards for Liang and his family, who was now in his 60’s during an extremely chaotic time in Shandong. One experienced in the field of protective services would certainly recognize the need for such in times of strife.

Militias were also becoming more and more commonplace in Shandong due to the growing criminal activity. Was this group a militia? Was their symbol the mantis? Was Liang the militia leader? He was a respected escort-master who may well have been looked to as a local leader. More questions, few answers.

Another question, were they a gang of hoodlums brought together by ill circumstances to bully and harass others? Asserting their will over those weaker than themselves? This last part is doubtful due to Song, and another friend of theirs, Wang Rongsheng, being from wealthy families.

Perhaps, during the height of a major catastrophic event, and surrounded by a collapsing dynasty, Liang was simply teaching martial arts to this next generation for a hobby? Silly, when we lay it out that way, but entirely possible.

We have no definitive reason why any of these boxers, with the exception of Wang Rongsheng came to claim Liang as their teacher. We can however look at the obvious connection to the plum blossom society, and how this popular boxing wave came to influence mantis boxing as it progressed toward the 1900’s. Possibly determining when praying mantis boxing began to change.

The Boxer Uprisings

Plum blossom boxing was highly popularized by the time these 5 boxers were in their 30’s and 40’s. The style was also directly, or indirectly tied to the Boxer Uprisings many years later. According to Dr. Peter Lorge, and Dr. Tom Green, méihuāquan was a popular style, or group of martial artists of the time, which also held a folk religious element along with it.

Plum blossom boxing was spread through marketplaces when their followers/practitioners visiting villages and cities in the northern regions of China. Said boxers would meet up with other martial artists and share techniques in a cross collaboration. The art spread through various provinces such as - Henan, Hebei, and Shandong [Green 2016].

Dr. Ben Judkins mentions these plum boxers in his extensive writings on Martial Arts as Brand. Judkins writes, “Talent attracts talent.” which could help explain why these younger, accomplished boxers with prior experience in other styles, ended up tied by lineage, to two biaoshi (escort masters) that came before them - Li San Jian, and Liang Xuexiang.

Judkins further writes -

“However it would appear that there have been numerous cases where local martial artists wished to capitalize on the marking[sic] power of the dominant style or “brand” but for one reason or another could not officially enter the new institution or retrain. The very rapid spread of Plum Blossom Boxing across northern China in the late 18th and 19th century is a good example of this.

Members of this style, sometimes associated with millennial folk religious movements, were a common fixture on training grounds and at village markets in a number of northern provinces. Today there are a very large number of “alternate lineages” within the Plum Blossom tradition, some of which share more commonalities than others. Practitioners of the art occasionally point to this proliferation of clans as evidence of the great age of the art. However, we actually have some good documentation on the history of this particular style.

It appears that in the second half of the 19th century a relatively large number of small local fighting styles, some of them more closely related than others, started to declare themselves “Plum Blossom” schools by fiat, essentially appropriating what was a regionally very successful brand, without having to totally overhaul their teaching structures. In this way the total number of unique local styles in the region was reduced, and the relationship between the name “Plum Blossom” and any fixed body of techniques was stretched and twisted”

Jiang Hua Long and his friend Song Zi De were the first to claim the moniker of the plum blossom, branding the style as ‘Plum Blossom’ Praying Mantis Boxing. Hao Lian Ru was the blood brother of Liang’s son, Liang Jingchuan, who was much older than him and the 1st disciple of Liang Xue Xiang. Hao later went on to distinguish his line of mantis as something different than the others - Tài Jí Méi Huā Táng Láng Quán, or ‘Supreme Ultimate Plum Blossom’ Praying Mantis Boxing.

Tai Ji is oft used as a way to define something as ‘the source of all things’. This was likely a way for Hao to declare (or brand) that he was in fact the 1st of Liang’s disciples. The closest to the core. However, when this happened is debatable. Such political pettiness is likely to have happened after Liang Xuexiang’s death in 1895 at 85 years old.

If Lorge is correct that much of the plum blossom moniker came after the Boxer Rebellion, then we can narrow this down to sometime after 1902. If Liang Xuexiang was the bearer of the mantis torch prior to all of these boxers, and it was not a brand invented after his passing, then it is likely the plum blossom blend of techniques also did not appear until after his passing, and after the boxer uprisings.

The references to the plum blossom go deeper as we explore a few of the mantis boxing tào lù (forms, or choreographed boxing sets). Although this is subject to debate, these boxing sets are the commonly believed ‘older’ sets from mantis boxing. They exist in all of the main lines with the exception of 6 harmony mantis, which came later in the 5th generation by conjoining with a different boxing style altogether (Liuhe).

Mantis Boxing Sets - Tào Lù

A note on these boxing sets before we establish their plum blossom connection. The common forms that exist between the lines of — plum blossom praying mantis boxing, supreme ultimate praying mantis boxing, and qī xīng (Seven Star 七星) praying mantis boxing, are all different from one another in execution. None of them have the same moves/patterns within the choreographed set of fighting moves. This makes it next to impossible to tell which version is ‘correct’, or an original, and further solidifies the fact that boxing techniques and styles of the time, were fluid.

We can however rule out seven star mantis as being the original, since Wang Rongsheng never studied under Liang Xuexiang. Wang’s claimed teacher, Li Sanjian practiced Red Boxing (Hong Quan), not mantis boxing. Li San Jian was in his 70’s in 1888 when Wang started training with him, and died a few years later in 1891. So it is difficult to assess how much ‘knowledge’ was transferred to Wang from Li in that time, and if fighting was the true nature of their relationship.

It is also important to note that Wang was from a wealthy family, and thereby did martial arts as a hobby rather than as means of employ. Li San Jian however, was a famous fighter and biaoshi. Wang, also ‘purchased’ his degree in the 1890’s (a common form of corruption taking place at this time due to the imperial examination system being extremely difficult to pass). Wang failed the exams three times previous to purchasing his degree. Wang, and his family quite possibly hired Li Sanjian for his protection services/knowledge, and Wang could have studied with him during this time. But their relationship is unknown to us, and not relevant to our current, and further exploration of the plum blossom connection to mantis.

Ultimately, finding the original quickly narrows down to — Plum Blossom Praying Mantis (Jiang and Song), Tai Ji Mantis (Sun Yuanchang), or Tai Ji Plum Blossom Praying Mantis (Hao Lianru). Perhaps Hao and Sun’s ‘taiji' mantis is closer to the true mantis, if there ever was such a thing. Or, at least closest to Liang Xuexiang’s teachings? Perhaps this is why they named branded it with the taiji? As in ‘closest to the source’.

The fact that the forms (taolu) from each of them is also different, tells us that even within this ‘style’ of mantis boxing, the forms were subject to independent interpretation rather than a dogmatic system of practice. Due to the appearance and consistency of all three of the core boxing sets (albeit executed differently from one another) in ‘seven star’, ‘taiji’ and ‘plum blossom’ lines of mantis boxing, allows us to trace the forms Luán Jié (Intercept 攔截), Bā Zhǒu (8 Elbow 八肘), and Beng Bu (Crushing Step 崩步) at least as far back as this 4th generation of boxers.

I have no known record of who created these forms at the time of this writing. There is uncorroborated claims that Liang Xuexiang wrote three manuscripts and listed some of these sets within. Until I can verify that, it is unsubstantiated. We may never know.

Because these boxing sets show up in plum blossom praying mantis, supreme ultimate praying mantis, and seven star praying mantis, we can conclude that they either a) existed prior to this generation, and were taught by Liang Xuexiang, or b) were created by this generation and spread down each branch from there; each style having different versions of the form based on the boxer teaching it. Having no verifiable written records makes it difficult to pin down an absolute origin, but it is important to note Esherick’s writings again here as a refresher - ‘boxers and their methods were more fluid and subject to variation from boxer to boxer.’

Wang Rongsheng, the founder of the seven star praying mantis branch was close friends with the ‘plum blossom’ praying mantis boxing founders, and around the same age. Wang assuredly learned mantis boxing from these boxers, his friends, since he did not learn it from Li San Jian. This we can discern from a close study of our mantis boxing timeline, and exactly when he is noted as meeting his claimed teacher, Li San Jian.

Since the boxing sets Crushing Step, Intercept, and 8 Elbows are often the topic of discussion when it comes to ‘original forms’, I’ll focus on these in more detail while additionally notating other forms that offer significant points of interest, if in name only.

Note: These observations are based on the versions of the form(s) that I learned and witnessed via other boxers. Mantis forms are ripe with variations from one line to the next, even at times within the same branch/line. Thus making it extremely difficult to make any statements in absolute terms.

Lán Jié (Intercept 攔截)

The same double block is found in Gongliquan.

The version of Lán Jié that I learned, as well as others I see out there, is precipitated by a strange movement pattern performed in the air. This pattern makes little sense out of context, but the pattern in the air is clearly a plum flower. An homage to plum blossom boxing and a strong indication that this set was assembled by this 4th generation of boxers, or at least this was tacked on.

The opening move of the form that follows the salutation is synonymous with a version of the plum blossom boxing set -> double rising hooks followed by double palms/waist chop. This is the same opening move of the plum blossom form/boxing set that still exists today. Instead of hooks (another brand as I discuss in The Mantis Hand was nothing more than a Mantis Brand) the plum blossom version uses two upper blocks with fists. Similar to gongliquan (power building boxing).

By itself one could argue that this was just a technique that was common to the region at the time. However, when placed immediately after the opening symbolism and combined with other factors that follow, it stands to reason that it came from plum boxing rather than the other way around.

Other common techniques overlap with plum boxing as well: crashing tide, closing door kick, recede/block/kick, block/circle/trap strike, seize leg, lifting hook to the topple, and more. All show a) there was a common vernacular, or library of techniques, (see What Can BJJ Teach Us About Qing Dynasty Martial Arts? - Randy Brown - MAS Conference 2019) in the region at the time, and b) given the redundancy of these two sets and plum boxings popularity compared to mantis, that Lán Jié was likely created after the plum blossom boxing craze.

Given the heavy influence and symbolism of plum boxing within this set, it is far more likely this form was created or altered after the boxer uprising when forms proliferation truly began. However, this is difficult to know for sure without documented dates of creation. Another commonality with this set as well as other mantis sets like crushing step, and others (yet not Ba Zhou), is the repeated engarde position found in the meihuaquan (see photo).

Bēng Bù (Crushing Step 崩步)

Bēng Bù (Crushing Step 崩步) is a prevalent tào lù (boxing set 套路) of praying mantis boxing. It stands as one of the more popular fighting sets on record for the style. It is also a common boxing set practiced by a few of the branches. Although the name translates as 'Crushing Step', this is a bit of a misnomer.

This form also embodies the influence of plum blossom boxing. The ‘engarde’ position known as ‘mantis catches cicada’ shows up in bēng bù right at the beginning — second move. In Crushing Step as well as in other mantis sets, this engarde position is branded with the mantis hooks instead of the signature open palms found in plum blossom boxing as seen above. This clearly disrupts the idea that this was a combative move in and of itself. A heart crushing blow to many of us who spent great efforts trying to ‘decipher’ the fighting application of that move.

In the end, it is nothing more than a branded engarde position taken from plum blossom boxing. It could also be commonly used by boxers from varying styles accustomed to duels at the time. Although, in my experience with studying over 50 forms from a variety of northern Chinese boxing styles, it does not appear that often in other sets/styles.

Additionally, the end of Crushing Step, and Intercept, both have a 180 degree turn to this ‘mantis catches cicada position, or engarde with hooks. The plum boxing set ends with the exact same 180 degree turn, the exception being the use of open palms vs hooks.

The Tiger Tail Kick

Plum Flower Maiden Dancing from Pole to Pole. Circa 1880. Source: Wikimedia (though I believe that Stanley Henning was the first person to publish this image in his essay for Green and Svinth.)

At the end of the first road of bēng bù, there is a move often referred to as a ‘tiger tail kick’. There are versions of crushing step with one instance of this move as you start the second road, and other variations end the first road with this move, and then repeat it in the opposite direction before heading into the second road of the form. Regardless, its roots lie in plum boxing.

Thanks to another article done by Ben Judkins on his Kung Fu Tea blog, I found a drawing of this exact same move. The article - “Research Notes: “Background of Meihuaquan’s Development During Ming and Qing Dynasties” By Zhang Guodong and Li Yun” discusses the influence meihuaquan had on the area of Shandong during the late 1800’s. This same ‘tiger tail kick’ move, as seen in the drawing from 1880, is inside the meihuaquan forms as well as Crushing Step.

This influence on a staple mantis boxing form such as bēng bù draws into question the age of the form, and perhaps points to a newer origin story for this boxing set thought to be at one time over a thousand years old.

Bā Zhǒu (8 Elbows 八肘)

Bā Zhǒu is claimed to be one of the older sets in the lineage. By outward appearance, although mutated from line to line, it seems to be one of the only forms consistent among seven star, supreme ultimate plum blossom, and plum blossom mantis. It would therefore hint that this form [whichever version is original], is handed down by Liang Xue Xiang, and perhaps those before him.

Additionally, and perhaps more significantly — in review of the various versions of this form ascribed to the different branches of mantis boxing, there is a distinct lack of the ‘plum blossom influence’ in the set unlike crushing step, and intercept. In a closer look at this 4th generation of boxers when they fractured into separate lines, based on this evidence it is highly likely in my opinion that this is the oldest mantis boxing set.

Bēng bù and lán jié are suspicious when we see the heavy plum blossom boxing influence represented within them. In both seven star, and plum blossom mantis boxing lines. This can further be brought into question as we look to what other significant geopolitical factors took place in this region/time period.

Rebel Boxers

These plum boxers were subsequently connected to the Boxer Uprisings as we travel closer to the turn of the century. Zhao San Duo, a famous plum boxer and rebel of the time, they were connected to the uprisings not necessarily in ways that would seem obvious. Judkins writes regarding the plum boxers/sect in his article on Zhao San Duo, “the group expelled anti-Christian, and anti-Qing extremist factions.” They were, as well as other martial artists of the time, called upon to engage as a militia group in times of need.

However, Judkins cites the work of Joseph Esherick on the Boxer Uprisings and goes on to further mention the following specifically about Zhao San Duo -

“Esherick reports one very interesting example of “image policing” in his discussion of the relationship between Plum Blossom boxing and the aftermath of an outbreak of anti-Christian violence in 1897 (The Origins of the Boxer Uprising. California UP, 1985. pp. 151-159.).

Zhao San-duo was a noted local Plum Blossom teacher who had a few thousand students and disciples (including many yamen clerks and secretaries) in the Liyuantun region of Shandong. He was probably not a wealthy individual, but his father was a degree holder and he seems to have had some amount of local influence. While he initially resisted being caught up in local events, he ultimately could not withstand the demands to back his fiends and students in the face of persistent communal violence.

During the spring of 1897 he was effectively pressured by his students to become involved in a dispute between the local community and the area’s Christian population. A church (still under construction) was attacked, homes were looted and many people were injured in the clash (one person was reported to have been killed). The Christians were effectively driven out of the local community and the site of their former church was reallocated as a village school.

This action was well received locally and local officials were sympathetic to Zhao and his cause. However, from that point forward he increasingly aligned himself with radical (and sometimes even anti-Manchu) figures. This trend worried the other elders of the local Plum Blossom clan. They did not want to be associated with community violence, anti-Christian violence or even the suggestion of sedition.

These elders met repeatedly with Zhao. However, when it was clear that he would not change his path they agreed to part ways, but forbade him to teach or practice under their name. In effect, worried about the damage and disgrace that he would bring to a very successful brand, the Plum Blossom clan excommunicated the increasingly revolutionary Zhao.

He selected a new name for his style, the Yi-he Quan (Boxers United in Righteousness). This should sound very familiar to students of late 19th century Chinese history. Just as the elders feared, the subsequent actions of the Yi-he students in the Boxer Uprising severely damaged the fortunes of martial artists around the country.

The above is a significant indicator as to not only the popularity of plum blossom boxing at the time, with Zhao having “a few thousand students”, but what would ultimately also come to affect our mantis boxers in Shandong.

We see not only the influence of plum boxing on mantis boxing, but this further evolves into a new intersection with the Boxer Uprisings and the political leanings of at least one of our boxers. As the Righteous Harmonious Boxers as they were called, grew in popularity, so too did their influence on Jiang Hualong. Was Jiang involved in the uprisings? Or was he just an admirer of how they stood up to the western powers who were forcing their way into China, and specifically Shandong? Or was Jiang a supporter of the yi-he boxing movements anti-Christian agenda?

The following forms are noteworthy due not only to their connection to the plum blossom, but the boxer uprisings as well. Whether this is due to religious, cultural, or rebellious reasons is unknown, but it offers further evidence of our boxers being influenced or connected with meihuaquan.

Plum Blossom Fist - creator unknown

Plum Blossom Road (Meihua Lu) - Jiang and Song

Righteous Harmonious Fist - Jiang Hualong

Flower Arranging - Wang Rongsheng

Double Flower Arranging - Wang Rongsheng’s forms

Of particular interest is Jiang Hualong’s set - Righteous Harmonious Fist. According to Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo in their book ‘Jing Wu The School That Transformed Kung Fu’, any association with the boxers involved in the Boxer Uprisings in the early twentieth century would have been considered detrimental to one’s reputation. While we have no record of what year this form was created, if it were prior to the reformation period and the creation of Jing Wu, it raises an interesting question as to why Jiang would keep the name, given any association with the Rebel Boxers was perceived as negative.