Guest Appearance: Mantis Boxing, BJJ, Self-Defense and heresy in martial arts (Ep31 - The Tai Chi Notebook Podcast).

Good Afternoon All, Back here in New England after spending a week at Martial Arts Studies Conference 2024 in Cardiff, UK. The conference was exceptional, but more on that later. For now, I’ll highlight one of the many outstanding encounters of the trip. I had the distinct pleasure this past week of meeting and sitting down with…

Good Afternoon All, Back here in New England after spending a week at the Martial Arts Studies Conference 2024 in Cardiff, UK. The conference was exceptional, but more on that later. For now, I’ll highlight one of the many outstanding encounters of the trip.

I had the distinct pleasure this past week of meeting Graham Barlow of The Tai Chi Notebook Podcast, and Blog. I had seen Graham’s blog a few years ago but never had the honor of meeting him. Graham is a long time practitioner of Chinese martial arts: Tai Chi and Choy Li Fut to name a couple. He then migrated as I did to Brazilian jiu-jitsu where he now spends his time teaching and sharing his passion with others.

Graham and I had tons to talk about, and the dialogue continued when opportunity arose between panels or at the end of the day. Without spoiling it, I’ll now introduce you to one such moment when Graham suddenly pulled out a recorder, and invited me to an impromptu podcast which he pulled off masterfully.

Enjoy the discussion, it goes in my bucket of favorite chats.

Ep31: Mantis Boxing, BJJ, Self-Defense and heresy in martial arts

The Tai Chi Notebook Podcast

For more good stuff from Graham

Find him on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC1SJdsrGOYU45CFU9naMHHg/

Find his website and podcast:

http://www.thetaichinotebook.com/

Facebook:

@TaiChiNotebook

Tai Chi Underground - Project: Combat Methods

Check out this exciting new video project currently underway!

Welcome to my new project. I’ll update this blog post as we release videos each week. Stay hooked!

Find out why I am making Tai Chi videos…

Tai Chi History

If you are interested in the history of Tai Chi, check out this post:

Tai Chi vs Mantis Boxing

Here is a research project I’ve been tinkering with for years. A comparison of these two martial art styles; their commonalities, shared fighting techniques, and symbiotic combat principles.

Tai Chi Combat Methods

STRUM PIPA

Known as - Strum Pipa, Strum the Lute, or Play Guitar, this move is found in the first road of the Yang style Tai Chi long form, as well as the 24, and other sets. The move is performed twice in the form and mimics a person playing a lute/guitar/pipa. This redundancy of 2x could be an indication of this moves multiple primary combat methods. One method is depicted in this video, others will appear as parts of the other moves in this series. Often when viewing this move in tai chi today, it has been simplified with the hands and looks identical to Raise Hands Upward, which has a very different application.

HIT TIGER

Hit Tiger -- found in the section 2 of the Yang tai chi long form. Often portrayed with large sweeping arm rotations. The movements in the form were exaggerated (large frame) but originally had a shorter frame as depicted here. More in line with the application.

BEND BOW SHOOT TIGER

Bend Bow Shoot Tiger is the final movement of the Yang long form that closes out section 3. The move can easily be mistaken as a block/counter-strike, except the footwork and angles are all off. As with many moves found inside Chinese martial arts forms, a punch is not exactly a ‘punch’.

RETREAT ASTRIDE TIGER

Retreat Astride Tiger appears in the third road of the Yang Tai Chi long form. By outward appearances, the move can be mistaken for White Crane Spreads Wings. The two have very different fighting applications.

BRUSH KNEE

Brush Knee appears in the 1st road of the Yang Tai Chi Long Form. It is repeated 5x in this road, and 4 more times in the remainder of the form. Clearly, a significant fighting technique to the author of the form.

In road one, Brush Knee is interspersed with Strum Pipa . Brush Knee - Strum Pipa - Brush Knee (3x) - Strum Pipa - Brush Knee. Why do you think this is? (easter egg)

See the Unseen - In 1911 this style was converted to a health practice from a fighting art as part of the reformation period in China. A tool to help strengthen the populace using their now defunct martial arts (due to firearms and changes in warfare).

As such, having people balancing on one leg without a partner to grab is challenging. Therefore what is represented in the form is an 'abbreviation' of Brush Knee's true fighting intent shown here.

From A Few Years Prior

Grasp Sparrow’s Tail

Grasp Sparrow Tail, the one and only. Yang Lu Chan's masterpiece sequence from Qing dynasty Chinese Boxing. This is Yang's Cotton Boxing (miánquán 棉拳), or more widely known as Taijiquan (Tai Chi). The Yang style long form is riddled with this move. I have spent years trying to figure out how this move worked, and it is one of the handful of Cotton Boxing techniques that has continued to elude me. Until now. This is by far an amazing discovery. I am very thankful for whatever daemon's have been visiting me of late, and showing me these moves. A few weeks ago I was watching Sonny from Beijing Shuaijiao (check out his channel for more good stuff), play around with Part Horses Mane; another move from Yang style. I noticed something he was doing and it sparked an idea to play out. Thanks to Holly, Vincent, Don, and Thomas for putting up with my ramblings and pushing them around for a few days while I worked on it. Apologies for those in Whole Foods that had to witness the disruptions. Without further ado, check out the video Max shot so we could put this out there for all that have studied Tai Chi and wondered what these moves do. There are more coming, but this is by far one of the coolest sequences that shows how high level Yang Lu Chan really was. You don't develop chains like this, unless you are at a high level in your game.

Embrace Tiger Return to Mountain

Yang's Cotton Boxing has innumerable combinations of moves that transition from one to another. Here we show the use of 'Needle to Sea Bottom', to setup 'Embrace Tiger Return to Mountain'. Embrace Tiger is similar to 'Grasp Sparrow Tail'. The entry is different, but then the next three moves are the same/similar.

Diagonal Flying

When grappling in the flank position, and tied up, Flying Diagonal showed up as a good counter to our opponent’s counter for Double Seal Hands, or in general - if our opponent postures up while in this position. Check out these nuances and details to add Diagonal Flying into your arsenal.

Rise from the Ruins: Embarking Into A Dying Art of Boxing

An Essay on my Early Years in Chinese Boxing Dance

Martial arts forms (kata, tào lù) are more plentiful today than in any time in history. They are widely disseminated in a variety of martial arts schools/styles across the United States, and around the world. A majority of ‘traditional martial arts’ competitions today, are centered around stylists competing with their form of choice. One is hard pressed to enter a school of karate, kung fu; kempo, tae kwon do; or tang soo do, etc. that isn’t consumed by a curricula filled with form after form. Once you complete one form, you’ve earned the ‘privilege’ to learn another...and another...and another.

Years into my training, I went on to scorn these empty shells. For quite some time actually. One reason I held such admonishment toward ‘forms’, was having…

Finding the Mantis

I came across the art of Praying Mantis Boxing in of all places - New Hampshire, USA back in the 1990’s. I was correcting course in my life and on a quest to empower myself with martial arts training and the skills to know how to handle myself. A desire of mine since childhood. I immediately fell in love with the art, even in it’s corroded state.

Sadly, time has not been kind to this, and many other Chinese boxing systems. Much damage has been done over the past century or more, as these arts were no longer used for combat. By the time I began my training, it was difficult to tell what Mantis Boxing was in its original manifestation.

What remained was largely boxing sets (choreographed fighting moves in the air known as forms/kata/taolu), myriad drills, and a plethora of archaic Chinese weapons techniques of a bygone era.

Due to this decayed state my journey early on with this art was difficult and fraught with challenges in finding answers, or seeing an effective use of these movements in sparring/combat. Thankfully, we do have those who carried the torch over hundreds of years; bringing with them the keywords of the style as well as the old ‘boxing sets’ which allow us to view into the past.

I have dedicated over 20 years to mantis boxing, as well as other stand-up fighting arts in a quest to reconstruct the art so that it is intact for my students going forward. Through traveling, studying with experts, training, competing, teaching, sparring, researching; anything I could find that would yield improvements. We move forward with methods so that others, like you, can receive a fighting art that is versatile, effective, and well…quite frankly - RAD!!!

My efforts to ultimately reshape, redefine, and revolutionize the art have created a new version of mantis boxing that is relevant for self-protection in modern times. This last part being of great import to me. I believe any martial art should be applicable and functional. Ensuring not only its own survival for future generations, but also the survival of its practitioners.

BOXING SETS

Throughout my martial arts career I have had many opinions on forms/boxing sets. These viewpoints have shifted like the swirling tides along the rock-strewn coastline of Maine. Early on, when I began my training I was heavily invested in these sets. They were, after all, the primary method of transmission for the art that I chose to study - Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳), and before that, Tae Kwon Do.

Mantis Catches Cicada - circa 1999

Mantis boxing was handed down to me by my early teachers, and their teacher’s before them, with forms as a primary method of transmission. Completely absent of the mechanical inner workings that made these moves functional with live opponents in actual hand-to-hand combat. In all fairness to the first mantis coach I had, was up front with me from the beginning about this. I was under no illusions.

Martial arts forms (kata, tào lù) are more plentiful today than in any time in history. They are widely disseminated in a variety of martial arts schools/styles across the United States, and around the world. A majority of ‘traditional martial arts’ competitions today, are centered around stylists competing with their form of choice. One is hard pressed to enter a school of karate, kung fu; kempo, tae kwon do; or tang soo do, etc. that isn’t consumed by a curricula filled with form after form. Once you complete one form, you’ve earned the ‘privilege’ to learn another...and another...and another.

Years into my training, I went on to scorn these empty shells. For quite some time actually. One reason I held such admonishment toward ‘forms’, was having learned over fifty of them in my first seven years dedicated to wu shu (martial arts) training.

As soon as I would finish one form, I would be handed another; whether by my request for some shiny new toy I was enthralled by, or a suggestion by the instructor(s). It became impossible to remember all of these sets, and far too time consuming to practice them all; little did I understand why at the time.

When it came to fighting and sparring in the martial arts schools I attended, the combative application was entirely disembodied from these forms; like a warrior’s sword detached from it’s handle - once upon a time a dangerous weapon to be feared, now - a toothless tiger.

Crossover from form to fighting never existed in the schools that I trained in. We would warm-up, practice movements, shadow box, and spar the last few minutes. When it came time to spar with classmates, it usually manifested as ‘bad kickboxing’. To be fair to these coaches, their passion lied with what they were teaching - forms, not fighting.

I kept sparring as much as possible, and competing in matches. I became increasingly frustrated over time. I would ask myself - “wasn’t the point of martial arts to learn how to defend yourself? Wasn’t the ultimate goal to become empowered? To know secret ways to disable attackers, fend off bullies, submit miscreants that wish harm upon us, or protect our families?” I was profoundly confused by the training practices I was experiencing, versus what I had envisioned martial arts being meant for.

COMBAT ARMS

Flight School - aka ‘Fight School’ - Alabama 1990

Having been in the military for a short period of my life, I was used to an environment built on training for ‘combat’. We certainly didn’t pretend to drive tanks, or fly invisible helicopters, fire imaginary bullets downrange, or use toy weapons. Lessons on my martial arts path were not adding up with my life experience. Why was a bulk of my time training, just pretending to fight opponents in the air???

While I was stationed in Texas, I briefly undertook the study of taekwondo until my military units’ training schedule was ramped up and I could no longer juggle it in. It was enjoyable at the time, but certainly wasn’t my favorite martial art style. I had a good teacher, and I enjoyed my time there (however brief), but the art was too simple, and too linear for my taste. However, to the instructors credit, in those classes we spent a bulk of our time sparring.

Years later, as I was well into my Chinese martial arts training, I knew something was amiss with the way I was being trained. I tried taking moves from some of the forms I had learned, and experimented with them while sparring in class. This was often met with punishment being doled out by my opponent’s barrage during my risky ventures. Still, I tried to pull them off, but rarely did I find success.

Instead of introducing something new into my game, it became increasingly easier to rely on a few well-timed tricks, and speed/power to overcome my opponents. Sticking to the attacks/counters I was already good at. Reinforcing my current skills rather than growing as a fighter/boxer/martial artist.

Along the way I had decided, with the encouragement, and support of those around me, to become a martial arts teacher for a living. I was instructing at another school while this metamorphosis was taking place, and I opened a school with a friend of mine (2004). Off we went. Things did not improve; quite the opposite actually.

MIRROR INTO THE SOUL

Chris and Vincent - Tournament - Fall 2007

Now that I was teaching others full-time, the disconnect became crystal clear. I no longer had only myself to worry about, but my reflection staring back at me day in and day out. That reflection was my students. The truth became less than encouraging. My students would learn to move, perform cool looking forms, win competitions, but their fighting skills were no match for other martial artists such as boxers, wrestlers, judoka, etc.

I would ask myself - “Why someone taking western boxing for 6 months, could decimate a practitioner from kung fu, karate, kempo, tae kwon do, etc.?” In many cases, the latter had been training for years, or in some case decades.

I was thoroughly frustrated. I could suffer this no longer. We can be either part of the problem, or part of the solution. So I began to change the way I was teaching. I turned the focus of my classes more heavily on qín ná (the Chinese submission art of bone/joint locking and seizing).

In my early training, I had spent 4 years studying this discipline in tandem to my forms regimen. Dedicating multiple hours each week with partners in my first mantis school, and training with friends on the side. I felt better. It wasn’t perfect, but at least this was drilling with live people, and I was giving my students something that felt like martial arts/self-defense, rather than dance.

Jess and Mike - 3 Section vs Staff - 2005

I incorporated more ‘2-person’ hand-to-hand, and weapon sets from kung fu. Again, thinking that at least these had combative moves that involved a live partner to test against. All the while, I was still voraciously searching for answers.

I made it my mission to figure out how these forms worked in fighting; continuing my research; sparring as much as I could with friends that were traditional martial artists, and who were also frustrated by the norm. I turned the pages of tome after tome, reading historical accounts, watching videos. Any sources I could find. I turned my attention and focus to seeking out the core/roots of each system. Then…something enlightening happened.

A pattern began to emerge. I noticed a common theme while traversing my archaeological quest. How these styles began…

Tángláng Quán - two forms.

Yīng Zhuǎ - two forms and one partner set.

Tàijíquán - zero forms.

Hóng Jiā (Hung Gar 洪家) - one form.

Bāguà quán (8 Trigrams Boxing 八卦拳) - zero forms.

Xínyìquán (Intent Boxing 形意拳) - zero forms.

The writing was on the wall. In giant print. None of these styles started out with…so...many...forms. It was now obvious to me what I needed to do. Purge!

I embraced the ‘less is more’ philosophy. Even though, and unbeknownst to me at the time, I was still clinging to too much material. I discarded a bulk of the forms I had learned over the previous seven years. I no longer practiced, or taught them.

I sought out the core forms of the arts that I really enjoyed - Praying Mantis Boxing, Eagle Claw, Tai Chi, and Xing Yi. My intent being to ‘mine’ these forms for applications. To see what the original methods, movements were, so I could reconstruct these arts. Lofty goals to be sure, but I was not to be deterred. I was too invested at this point.

Traditional Long Weapons - Nationals Qualifiers - 2004 - Hershey, PA

After repeated polite inquiries with various mantis boxing teachers around the country, I was rebuffed by taciturn ‘masters’ unwilling to share their art. They behaved as if these forms were valuable magical secrets. As if I was asking for their priceless gems.

These teachers clearly coveted their core forms, like a mage who possessively guards their spellbook. I truly failed to comprehend why teachers were so disinterested in...teaching. I was ready and willing to learn! Why were they not helping me?

I had been learning forms a dime a dozen over the years, why were these such prized antiquities? Instead of welcoming an interested student, people were possessive; greedy, condescending, and cold. Again, rebuffing my ideals of what a martial artist is about.

During my journey, I learned that one “Grand Master” went so far as to try and sue people for stealing his forms. His organization actually attempted to copyright them. Other’s demarcated forms with fake moves so they would know when someone ‘stole’ it from a video, demonstration, or tournament. Marring the art, and further tainting it from its original intent and true purpose. This was chaos incarnate, and I simply did not understand it.

Martial arts in general, and forms specifically, are not something one can ‘steal’. One can copy someone’s form, but if the ‘thief’ does not do the work, or fails to comprehend the intent of the moves within, they have no score.

If the purported burglar does the work - learns it, trains it, tries to perfect it; studies it thoroughly, then they have been taught. Perhaps, without them knowing they’ve been taught. As a teacher, or even a practitioner that wants their art to survive, is that not our ultimate goal and purpose?

Snakes Creeps Down (low single whip) Taijiquan demo - circa 2006

I continued on. I was teaching Tai Chi, and finding it difficult to find any sort of consistency from one person to the next when it came to the movements. Additionally, I could find no one that knew what these moves did, so there was no litmus test to know if a movement was ‘right’, or ‘wrong’. Every reason someone had, seemed esoteric, and subjective. Like judging dance, or art.

Xingyiquan was another focus of mine during this time. I enjoyed the premise behind it. I was told it was highly destructive, energetic, explosive, and aggressive. That it was a badass style of Chinese boxing. I was into that! A coach that introduced me to it, thought it would be a good fit for my…temperament.

Again, it seemed like the standards for success in xingyi, were completely arbitrary. The only ‘depth’ I was finding, was “sit in your san ti (3 dimensional shape) stance for 30 minutes a day.” Aside from that, I wasn’t told how to fix anything, or how to get better at xingyi. Later I realized - because you need to HIT things to really get it!!!

I sought out more coaches in these arts. I was successful in finding a tàijíquán/xingyiquan ‘master’; or so I thought. I attended one of his New England workshops and saw a glimpse of some power generation techniques in his Xing Yi that was of interest to me. I was told “he knows his stuff.” I thought there was something there, so I delved deeper.

I cobbled together some money and traveled to NYC to train with him. I hosted him for a few days at my house and school to help him share his art with my students. To hopefully glean greater technical knowledge from him on how these two arts functioned in combat.

It turned out to be forms, and hocus pocus. The tàijíquán was more incessant drumming of the most mundane minutiae. Where the hands should be aligned to maximize the ‘chi’. How one’s thumb position next to the quadricep was somehow important for mystical energy alignment. No accompanying demonstration of combat application to show why this mattered; nevermind how it was relevant in a real fight.

The renowned xingyiquan, a style known for its destructive capacity, and reputation for general badassery, was also more ‘air-fu’ (martial arts done in the air). Never hitting a punching bag, or pad. Never sparring. Never blocking and hitting. Just more chi (cheese). More pseudo-science. More nonsense. I left it behind.

In addition to the aforementioned individuals foul bathroom habits, and erratic/obnoxious behaviors, this arrangement was not working out to my satisfaction. Could ‘anyone’ in Chinese martial arts actually fight? Using Chinese martial arts techniques? I was growing more and more disenchanted.

Staff vs Staff - circa 2006

I returned to my research and training. Buying any books I could find. I read over 100 books on Tàijíquán, most of them a complete waste of time. It’s amazing how many words have been written about nothing.

I found the other arts lacking in content altogether. At least to my favor, tàijíquán is well documented. The most widely proliferated Chinese martial art in existence. Unfortunately, much of this is without practical meaning, and comprised mostly of esoteric beliefs, or lacking clarity of purpose. Whether this is intentional, or through innocent ignorance is certainly a matter of debate.

I took to searching for videos of the core forms of the styles I had chosen. For mantis boxing, I was able to find one of Bēng Bù (Crushing Step), but had no such luck with Lán Jié (to Intercept 拦截) , or Bā Zhǒu (8 Elbows 八肘). I ordered videos from China, familiarizing myself with the Chinese characters enough that I could search for books and VCD’s containing these sets, or anything close to them. I signed up for a Chinese class to assist in my quest.

My language venture did not last long. It turned out to be the same misguided approach to teaching language that is rampant in public, private, and even collegiate school systems across America even to this day. Grammar first. Years go by, and one is still unable to speak fluently, or converse with a native speaker. It is odd, that this failure of a student to speak, is not a measure of success for a language arts curriculum, or a teacher’s capabilities...

I digress. It so happened that in my research, I had come across an excellent resource of knowledge - an online forum for mantis boxers. Rich, and fascinating conversations took place in this venue, people seemed to be sharing knowledge and communicating their ‘secrets’ without reservation. I visited it from time to time, never saying much as they seemed far more knowledgeable than I; and there existed an hierarchy of lineage holders that I was not part of.

One day, I read a thread where an individual was chastising and insulting anyone who learned from a video. This individual was particularly demeaning, condescending, and harsh in their criticism. Stating matter of factly, that “anyone interested in learning mantis should only be doing so from qualified teachers; certainly not from video!!!”

This infuriated me. Who was this person to dismiss one of the three ‘primary methods of human learning’ (verbal, kinesthetic, and visual)? What position of expertise did they hold in life to stand up and blatantly proclaim that personal instruction (which I had experienced plenty of), was the ONLY way someone should, or could, properly learn. I balked at this notion. I broke my silence and chimed in.

My response was snarky; full of contempt. I no longer cared who held what position, or however ‘exalted’ they seemed to be. I had too many years of feeling like I had been duped. I rose up upon my soapbox and fired back my reply - “blah, blah, blah, - insert stuff about learning types and video being a modern tool to assist people, - blah, blah, blah”. Then (I paraphrase here) - “perhaps if you mantis masters were not so rude and possessive with your forms, those of us whom you shun, would study from you, rather than be forced to pick scraps from videos.”

Shortly thereafter, I had a reply to my post in the thread. I opened it, adrenaline coursing through my veins. I awaited the inevitable online battle that was sure to ensue. Knowing, full well, some virtual vitriolic response from the original author of the post was there unopened in my inbox. Instead, I was greeted with - “Come to San Diego. I’ll show you the core forms of mantis.”

What!?!?!?! I was stunned. Stopped dead in my tracks. This was not at all what I expected. Who was this person? What did they know? Why were they so quick to offer and share what everyone else tried to hide?

I looked at the member profile. They were a member for years, yet barely posted a thing. I found a name. I Googled it. Nothing (Google was in it’s infancy then). I searched further; looking deeper. I finally found some grainy black and white videos of this Mantis Boxer doing the form Bā Zhǒu (8 Elbows 八肘), and another of one of his black belts doing Tōu Táo (Monkey Steals the Peach 猴子偷桃).

I could tell from the way they moved that they knew how to fight. I replied. “I’m interested. Let’s discuss.” Phone numbers were exchanged. A time set to talk. After an hour or so long phone call, and a lengthy discussion on his background, methods of teaching, and why he only works the core forms of Mantis, I booked a flight and hotel to San Diego, CA. Off I went.

I never looked back. In my first 15 minutes of meeting with this mantis boxer, I learned more about ‘fighting’ than I had in 7 years of kung fu training.

“Where do you look when you fight?”, he asked. I thought about it, and replied with “I look off to the side of my opponent.” He paused, a quizzical look on his face. Apparently he hadn’t expected that response. Then came his reply - “Not at them?” I said, “No, but I’ve been told all things of the sort - look in their eyes. Watch their head…” He asked me why I look off to the side. “It’s just something I do.” I replied. “It seems to work better for blocking.” He grinned.

“You’ve figured something out”, was his response. This made me feel good. I was eager to hear more. He proceeded to explain the reason behind why I was doing this, why it worked, and drills to prove it. Beyond that, he offered up the name of a ‘principle’ to go along with it. I was ecstatic. This was amazing! I had never experienced such a thing in martial arts; neither kung fu, nor tae kwon do. A ‘principle’ to teach fighting!?!?!

We then proceeded outside to work on Bēng Bù, a form from mantis boxing, and the one I was already familiar with. I was more interested in Lán Jié, since I had been unable to find anything solid on this form. However, being one of the core forms of Mantis that I already knew, it was a good launch point and gave us a way to see what one another knew.

We spent the next couple hours training in the parking lot of my hotel in the middle of the night, and well into the next morning. He left for home, and I spent the next hour scrambling notes and trying to calm down enough to sleep.

Qín Ná (Capture and Seize 擒拿) training - circa 2000

The next day we met for training around 9 a.m. We spent hours in the park, going over mantis boxing’s Lán Jié (to intercept 拦截) - as well as an application for each move. I was ecstatic and soaking it up like a sponge. We broke for lunch in the early afternoon and then met up with some of his students at his house. Training went well into the night again.

He asked - “How did you learn to block punches?” I stood there for a moment, realizing how little I had been taught on this. Most of my experience with blocking had been from taekwondo. I replied with something that I can no longer recall, but surely it was meek.

He had me pair up with one of his students to show him how I block. I was not allowed to move, and his student was to throw slow, controlled punches while I demonstrate my blocking skills. He destroyed me.

I blocked one or two shots, and then I was lucky to block one of every five after that. His student, had only been training 1.5 years. I was on my 7th year of training. Countless trophies under my belt, and a National 2x Gold, 1x Silver Medalist. I was running my own martial arts school, with a cadre of dedicated students looking to me to teach them how to defend themselves. This was humiliating, demoralizing, and excruciatingly raw. I felt like a novice. I felt as if I had wasted all my efforts. Years of training had been for nothing.

Right then and there, I had a choice to make. I could leave. Throw my hands up in defeat and walk away; quitting martial arts altogether. Or…I could do something less extreme - go home. Go home and lie to myself that I did fine. That he cheated, or that he did something nefarious to trick me. Pretend I was better than I was.

I looked at his student. Then turned my gaze upon the teacher as he stood there quietly gauging my reaction. My brow furrowed, I looked him in the eye with all my will behind me, and said - “teach me.”

Nationals Qualifier 2004 - Eagle Claw Form - Traditional Hand Forms. Hershey, Pennsylvania

To be fair, and honest, this was a bit of a rigged game. I wasn’t allowed to counter-strike, move, kick, clinch, or takedown. Real fighting, does not subsist with such a ruleset. Just blocking for any length of time is a failed strategy. One should be delivering parry/counter, block/counter, move/counter, etc. But the lesson hit home nonetheless.

I revisited everything I thought I knew, from the ground up. Asking him to go over stances, footwork, punching; anything I had already learned, or thought I learned. I wanted to know what was missing. The rest of the weekend turned to working on everything but, a form. He had to keep asking me - “Don’t you want to learn this form you came for?” [With a grin on his face of course.]

I spent the next few years going to San Diego twice/year, flying this coach to my school once/year. I met up with him at other people’s schools just to squeeze in whatever training I could get with him. Here was someone that knew how to fight, and did Chinese martial arts. I was all aboard.

As far as forms go, I learned Lán Jié, Bēng Bù (again), Báiyuán Tōu Táo (White Ape Steals Peach), 5th Son Staff, Saber, Da Dao (Military Saber), and a couple of 8-Step Mantis forms. I also learned how to block, punch, kick, and move; as well as throws, joint locks, and his core fighting principles to diagnose problems we have when sparring.

He helped me fix some forms I still held onto such as liánbùquán, and gongliquan, and my tai chi knowledge grew deeper and richer. As time went on, I had so much practical knowledge to work, the forms seemed superfluous, and nothing more than distractions.

I progressed, and my students became more and more in need of real skills. I went on to scorn forms in full force. Thinking them unnecessary, archaic, and highly corrupted distractions. Time-sucks that stole focus away from the more important aspects of martial arts - application, combat techniques, and self-defense skills.

Regardless of my disappointment and waning interest in forms, throughout it all, some part deep inside of me always held on to the notion that they are significant, important, and central to the art. Not in the possessive covetous way other teachers hold on to them, but in some more intrinsically valuable way.

Afterall, why were these core sets so important as to be handed down no matter what line of Mantis one studied? Why did the same set, with variations of course, exist across multiple lines in the family tree of Mantis Boxing? Why did almost every style of Chinese boxing have a ‘set’, or ‘sets’?

Ultimately I came to the realization that forms are treasure troves of knowledge. Ancient vehicles designed to carry the knowledge of a fighter’s system. Without the techniques, principles, and applications to go along with it however, or the work ethic to practice them tirelessly, they are worthless shells of long forgotten arts. The form, cannot exist without the function.

Without function, martial arts forms are merely martial dance. A non-practical artistic representation of a bygone mode of combat, and self-defense. There is nothing whatsoever wrong with people wanting to participate in the practice of this ‘dance’. It is only problematic when they believe, or are allowed to believe, that this practice of shadow boxing, will lead to the attainment of ‘real’ fighting skills.

In today’s world of video, books, a literate populace due to mass education, and the accessibility of martial arts schools and resources, forms are no longer necessary for a teacher to carry on an art of hand-to-hand, or weapons combat. As evidenced by judo, jiu-jitsu, muay thai, wrestling, filipino stick/knife arts, boxing, and more. All existing without the need for forms to muddy up the waters, or distract students from the true goal of martial arts - the dedicated practice of methods of violence to empower, embolden, and strengthen themselves out of immediate necessity, or the potential threat of such.

What is sorely needed for Chinese boxing to regain its rightful place on the mantle of formidable martial arts in the world of today is - less forms. More techniques. More application, and definitely more sparring.

Needle the Tiger - Using 'Needle to Sea Bottom' to setup 'Embrace Tiger'

Yang's Cotton Boxing has innumerable combinations of moves that transition from one to another. Here, Vincent and I will show the use of 'Needle to Sea Bottom', to setup 'Embrace Tiger Return to…

Yang's Cotton Boxing has innumerable combinations of moves that transition from one to another. Here, Vincent and I will show the use of 'Needle to Sea Bottom', to setup 'Embrace Tiger Return to Mountain'. Embrace Tiger is similar to 'Grasp Sparrow Tail'. The entry is different, but then the next three moves are the same/similar.

Additionally, we show Needle to Sea Bottom to Fan Through Back, and a counter to Embrace Tiger that leads to Retreat Astride Tiger.

Grasp Sparrow Tail, REVEALED!!! - Yang Lu Chan's Masterpiece

Grasp Sparrow Tail, the one and only. Yang Lu Chan's masterpiece sequence from Qing dynasty Chinese Boxing. This is Yang's Cotton Boxing (miánquán 棉拳), or more widely known as Taijiquan (Tai Chi). The Yang style long form is riddled with this move. I have spent years trying to figure out how this move worked, and it is one of the handful of Cotton Boxing techniques that has continued to elude me. Until now…

Grasp Sparrow Tail, the one and only. Yang Lu Chan's masterpiece sequence from Qing dynasty Chinese Boxing. This is Yang's Cotton Boxing (miánquán 棉拳), or more widely known as Taijiquan (Tai Chi). The Yang style long form is riddled with this move. I have spent years trying to figure out how this move worked, and it is one of the handful of Cotton Boxing techniques that has continued to elude me. Until now.

This is by far an amazing discovery. I am very thankful for whatever daemon's have been visiting me of late, and showing me these moves. A few weeks ago I was watching Sonny from Beijing Shuaijiao (check out his channel for more good stuff), play around with Part Horses Mane; another move from Yang style. I noticed something he was doing and it sparked an idea to play out.

Thanks to Holly, Vincent, Don, and Thomas for putting up with my ramblings and pushing them around for a few days while I worked on it. Apologies for those in Whole Foods that had to witness the disruptions.

Without further ado, check out the video Max shot so we could put this out there for all that have studied Tai Chi and wondered what these moves do. There are more Cotton Boxing videos coming, but this one is by far exceptional. A glimpse of how skilled Yang Lu Chan really was. You don't develop chains like this, unless you are at a high level in your game.

LEAN (Kào 靠) - 12 of 12 - The Keywords of Mantis Boxing

Lean (Kào 靠) - to lean against one’s opponent. Due to the heavy reliance upon grappling and clinchwork in Mantis Boxing, Kào is an important keyword when engaged close range with the enemy.

Postural Defense

Once we are entangled…

Lean (Kào 靠) - to lean against one’s opponent. Due to the heavy reliance upon grappling and clinchwork in Mantis Boxing, Kào is an important keyword when engaged close range with the enemy.

Postural Defense

Once we are entangled in the Clinch (Lǒu 摟), we lean in to protect our position, or risk being taken down, or pushed over. We use our foe as a support structure, leaning against them whilst engaged in grappling and clinchwork. This is synchronous with Adhere (Tiē 貼).

While we Adhere, we shore up our position by using Kào. If this becomes impossible, we should break range and secure a better position. Kào can shut down my opponent’s attempt at hip toss throws; dropping my CG making it difficult for him/her to get their hips (fulcrum) under my CG.

It also reduces chances for them using Crashing Tide; their posture would become compromised simply upon attempt. Another advantage provided by Kào, is buffering the double leg takedown. If we’re upright, our legs are within easy grasp, and shortens the time until their shoot. By leaning, I can sprawl easier and faster by dropping my CG and putting my weight down upon their shoulders.

Overall, if we can stay inside the clinch with a solid posture, and forward lean, we can use this pressure to time takedowns with applied force.

Applied Force

In addition to securing our position with solid posture, we can also use the shoulder to assist in our own throws. The shoulder is used heavily in a lean forward type motion to affect applied force. This assists in the execution of many takedowns such as Crashing Tide, Single and Double Leg Takedowns, Point at Star, Reaping Leg, Crane Spreads Wings, and more.

Mantis Captures Prey - How to Stop the Underhooks

The underhook is a powerful tool in the hands of an opponent who knows how to use it. They have leverage, control, and setups for numerous takedowns. So how do we stop our opponent from getting the underhooks? With this awesome move from Taijiquan called Fist Under Elbow, and what I like to call Mantis Captures Prey.

The underhook is a powerful tool in the hands of an opponent who knows how to use it. They have leverage, control, and setups for numerous takedowns. So how do we stop our opponent from getting the underhooks? With this awesome move from Taijiquan called Fist Under Elbow, and what I like to call Mantis Captures Prey.

In this video, we'll walk you through 1. The dangers of the underhook. 2. How to shut it down. 3. Counters from our opponent to watch out for, such as the 2nd hand. 4. Spear Hands, Eagle Claws, and Reaping Legs. 5. Hook, don't Reap - how to vary the technique based on our opponents position.

Like the video? Don't forget to hit subscribe.

The Dirty History of Tai Chi

The history of Tai Chi, correctly called Tai Ji Quan, disseminated to the masses, is often a mythical story that involves an art form thousands of years old with Taoist immortals, monks, and fairies. Commonly it is propagated that a non-existent type of magical energy, will heal the practitioners body and/or throw opponents without ever touching them. This is a fictional portrayal that in the West we call a fairy tale and in the East they call wu xia.

The history of Tai Chi (taijiquan, supreme ultimate boxing) is often taken with too much salt. The prevalent history disseminated to the masses often involves a mythical backstory thousands of years old, which includes: Taoist immortals, monks, and fairies. It is commonly propagated that the style of Tai Chi contains and revolves around a type of magical energy (known as qi) that will heal the practitioners body and/or throw opponents, without ever touching them. This fictional portrayal in the west would be known as a fairy tale, in China it is called ‘wǔ xiá’ (武侠), martial arts stories in theater/fiction popularized during early 1900’s China.

The notion that one can achieve unequivocal power, something akin to a superhero, without ever performing a day of ‘rigorous’ training, exertion, or hard work, is certainly the stuff of movies, myth, and legend. In contrast, the truth of tai chi’s history is far less enchanting to the laymen dabbling in an exotic art. The truth involves laborious acts, physical exercise, redundant practice, mental endurance, self-discipline, perseverance, and a history full of bloodshed, violence, and oppression.

General Qi Jiguang. Source: Wikimedia

The more accurate and verifiable history at the time of this writing shows that tai chi was developed roughly 400 years ago in Chen Village, Henan Province, China. It was known as less formally as ‘Cannon Boxing’, or the Chen family style. Like many Chinese martial arts it included hand-to-hand combat techniques common to the region, area, and time period. In 1560, General Qi Jiguang developed an unarmed combat system to train a militia to fight the wokou pirates. A group of Japanese pirates, which included Chinese ex-soldiers, privateers, and ruffians were pillaging the coastal villages and sea traffic. Based on the chapter in Qi Jiguang’s manual on unarmed combat, and the included illustrations, it appears by the trained eye that many of the depicted hand-to-hand combat methods are found in what is now known as tai chi. This points to a common pool of knowledge of fighting techniques.

During the mid 1800's Yang style tai chi was created by founder Yang Lu Chan. Yang, lived and studied in Chen Village and later went on to create his own system originally called 'Small Cotton Boxing'. Now known as Yang style tai chi, or taijiquan.

While many of Yang’s techniques mirror the Chen family boxing style, Yang included some of his own methods and merged them with the techniques of the Chen style, as any fighter will do throughout their martial journey when introduced to effective combat methods that they wish to amalgamate into their own art.

Yang’s life (1799 - 1872), or the life around him, was no stranger to violence and upheaval. Throughout his adult life he bore witness, knowingly, or unknowingly, to the impending collapse of China’s final dynasty, the Qing (1636-1912). Events happening all around Yang during his life include catastrophic flooding of the Yellow River (Huang He) (1851 - 1855, and many many more), famines, droughts, drug epidemics, two wars with the west (see Opium Wars 1839-1842, and 1856-1860), multiple rebellions (see Nian rebellion 1851-1868 and Taiping rebellion 1850-1864), and the encroachment of western powers on the Chinese populace, especially in and around trade ports.

As a result of losing both of the aforementioned wars, China was forced through treaty to pay reparations to the western powers, mainly by opening previously closed trade ports in the south and the north.

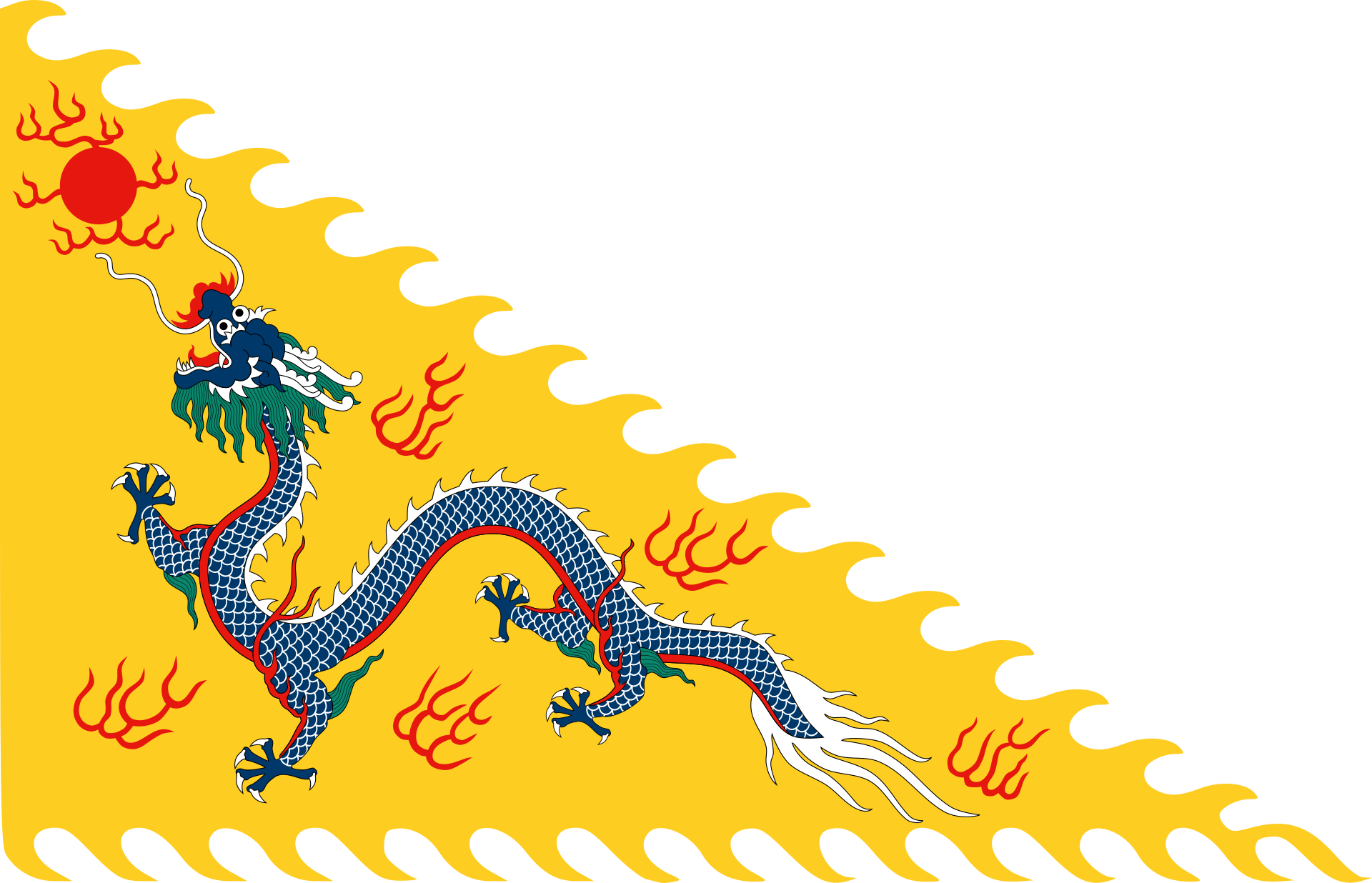

Imperial Standard of the Qing Emporer

Yang Lu Chan at one point in his life is recorded as being hired by the Qing court to teach armed, and unarmed combat to the imperial guards of the Manchu court in Beijing. Yang also disseminated his boxing art to his family.

Around the turn of the 20th century, decades after Yang’s death, the Chinese became disenchanted with their martial arts after repeated embarrassment in their confrontations with the west. More specifically incidents involving armed and unarmed combatants known as boxers, versus soldiers with firearms. Arguably the most famous of these incidents is known as the 'Boxer Rebellion', or more accurately the ‘Boxer Uprising’ (Joseph W. Esherick - The Boxer Uprising), which transpired over a four year time period with various encounters. The uprisings took place in Shandong, Hebei, and Tianjin provinces, as well as Beijing itself.

Port of Chefoo circa 1878 to 1880. Edward Bangs Drew family album of photographs of China, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Historical Photographs of China - https://hpcbristol.net/visual/Hv37-02

A century prior to this China was one of the most powerful civilizations on earth, with one of the most formidable military forces in existence. However, the industrial age in the west brought substantial change to warfare, along with the ability for nations to project global power in greater magnitude than ever before.

Although martial arts was considered beneath the scholar class, it was prevalent with boxers, soldiers, and guards in the employ of biaoju (security-escort companies). Local militia-men, sanctioned by magistrates commonly used armed/unarmed martial arts methods to quell local bandits and keep the peace. The Qing government in the 1800’s was preoccupied and impotent to respond to many smaller internal issues. The lowest expression of martial arts was associated with criminals, gangsters, ruffians, or charlatans which the Jing Wu and early 1900’s Chinese martial arts community tried to erase, or reverse.

The ‘boxers vs firearm’, or rather, antiquated military tactics versus modernized, industrialized weapons and strategies incidents that took place around 1900, likely further cemented the general public’s poor opinion of their nations martial arts, and of the ‘boxer’ overall. Three hundred years prior during the Ming dynasty General Qi, in his second book, published two decades after the first and post wokou battles experience, considered the act of training troops in hand-to-hand combat a rather fruitless endeavor when compared to the rapid and effective weapons training such a spears and matchlocks. This is evident since his second book omitted the unarmed combat chapter altogether.

Battle of Lafang 1900. Source: https://pin.it/5uubzq3xry77n5, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By the turn of the 18th to 19th century the Chinese having battled the western power’s sponsored opium crisis, repeated mass famines, floods, droughts that killed millions of people; rebellions that also killed millions more, and in addition to disease epidemics, were being called the 'sick men of Asia' by the international community. For a culture that was once in the not to distant past, more powerful than any other nation on earth this was humiliation on an epic scale.

At the end of the Qing (1910’s) and the beginning of the Republican era, a movement was initiated to change this stigma. A nationalist effort was undertaken to strengthen the populace and remove this cultural blight, or poor reputation. As a part of this movement and perhaps in an effort to keep their national arts from dying, Chinese martial arts teachers were commissioned to teach their methods for health, strengthening, and fitness, rather than for fighting.

This saw the creation of organizations such as the Jing Wu Athletics Association (circa 1910) of which tai chi, specifically Yang style, was a significant part of, as well as later the Nanjing Central Guoshu Institute in 1928. The directive of Jing Wu was primarily to improve health, and combat the 'sick men of Asia' label. Teaching physical fitness and health to affect positive national change. The Nanjing Guoshu Institute also propagated Chinese martial arts, and employed none other than Yang Chengfu, grandson to the progenitor of the style.

Yang Cheng Fu clearly had an entrepreneurial spirit that would help proliferate not only the Yang family art, but by proxy their predecessor, the Chen family, as well as the Yang offshoots of Wu family style Taijiquan, and Wu Hao style. Yang Chengfu took his grandfathers boxing art and taught far and wide, spreading it to the general public for health and wellness purposes around 1911.

Chengfu incorporated slow motion practice and longer movements as the focal point, removing much of the fighting application and combative elements taught by his grandfather, father, brother, and uncle. Thus was born a form of exercise that was all at once accessible to the young, old, weak, sick, and those of poor physical condition; to which rigorous exercise was not possible.

Prior to this Yang family taijiquan was taught strictly for combat, or a method of violence, or rather, defending against violence. It involved such skills as striking, throws, trips, takedowns, joint locks, sparring, fighting, and weapons training.

Forms practice (tào lù 套路), and push hands (tuī shǒu 推手) in contrast to present day, were likely a very small portion of the training. It is questionable if push hands had a significant role in the traditional combative training outside of skill building. It is possible that this portion of the training was derivative of the scholar class slumming in the martial arts world years after the art lost its teeth. A ‘game’ for people uninterested in fighting to pretend they are fighting.

It is also possible that given the heavy focus of the Manchu on wrestling, which was significant with the Han as well, that push hands was a tool for training wrestling skills in said competitions. The strategy of pushing an enemy in battle is ludicrous unless pushing them to the ground, or off a cliff. However, pushing someone outside a ring, or off a platform (lei tai matches) in order to score points, or win, holds a great deal of validity.

Qianlong Emporer observing wrestling match. Source: WikiCommons

Due to Yang Chengfu's efforts, and others around him, Yang style went on to become extremely popular, the most widely proliferated form of taijiquan throughout the world even to this day. The style’s true nature however is evident by some writers of the time:

Gu Liuxin writes of Yang Shaohou (Yang Cheng Fu’s older brother 1862-1930)

He used, “a high frame with lively steps, movements gathered up small, alternating between fast and slow, hard and crisp fajin (power/energy), with sudden shouts, eyes glaring brightly, flashing like lightning, a cold smile and cunning expression. There were sounds of “heng and ha”, and an intimidating demeanor. The special characteristics of Shaohou’s art were: using soft to overcome hard, utilization of sticking and following, victorious fajin, and utilization of shaking pushes. Among his hand methods were: knocking, pecking, grasping and rending, dividing tendons, breaking bones, attacking vital points, closing off, pressing the pulse, interrupting the pulse. His methods of moving energy were: sticking/following, shaking, and connecting.”

1949 Taiyuan battle finished. Source: WikiCommons

Three decades after Chengfu’s popular introduction of this rebranded art to the people, the Communist Party took control of China. As in past rebellions and changeovers of power, they once again outlawed the instruction of martial arts for the purposes of fighting. Mao Zedong, ever a student of history was well aware of the number of uprisings, rebellions, and dynastic turnovers associated with temples, and boxers. He burned the temples and banned the boxers.

During this period in the mid twentieth century, many traditional martial artists fled the country or were killed. The restriction by the government was certainly not in fear of a boxer, spearman, or swordsman attacking a tank, or machine gun nest, but rather due to a need to control the populace, a task exponentially more difficult when it involves submitting those trained in fighting arts (disenfranchised privateers, aka pirates). Martial training empowers individuals and empowered people are less willing to blindly succumb to oppression.

In 1958 after the period of unrest during the Communist Revolution (circa 1946 to 1949), China formed a committee of martial arts teachers. Choosing from a pool of those who stayed behind and used their martial arts training for coaching health/fitness, and/or those who had returned to the mainland from their exile.

The committee created what are known as the ‘standardized wushu sets’ - choreographed forms of shadow boxing summarizing and abbreviating the broad spectrum of China's legacy martial arts styles.

The wushu committee created the standardized sets for unarmed and armed styles, streamlining hundreds of styles in the north, and south that shared common techniques into one compulsory set to represent each - long fist (changquan) for the north, and southern fist (nanquan) for the south. In this consolidation effort, a few styles were left to stand alone gaining independent representation. These were, praying mantis boxing (tanglangquan), eagle claw boxing (yingzhaoquan), form intent boxing (xingyiquan), 8 trigrams boxing (baguaquan), and supreme ultimate boxing (taijiquan). Coincidentally these five styles were the advanced curriculae of the Jing Wu athletic association. Had they not been part of Jing Wu, it would be interesting to know if they would have survive long enough to be recognized by the PRC Wushu Committee.

These choreographed sets were then presented to the rest of world in a neat clean package, government regulated, and used to project China’s human martial prowess abroad, to include a trip to the Nixon White House where they demonstrated their skills. These boxing sets left behind the fighting elements of old, replacing them with sharp anatomical lines, clean corners, fancy acrobatics, and gymnastics. They became martial dance with 'timed' routines rather than the violent methods they once were.

As part of this standardization process in the 1950’s, the Yang taijiquan 24 movement form (a.k.a. Beijing Short Form) was created, and not by the Yang family itself oddly enough. This form represented Yang Style taijiquan (against the families approval) and went on to not only be a competition set, but a ‘national exercise’ that Chinese citizens would practice every morning in local parks for decades to come.

As China opened her doors to the rest of the world, westerners glimpsed the large organized gatherings of Chinese citizens performing their beautiful practice of the short form in parks day after day. Foreigners began learning this art while spending time overseas and via teachers who migrated to western countries proliferating their ‘art’ through hobby, or as a means of financial survival. The western world's interest was officially piqued.

Throughout the 1960's-70's and even into the 1980's, there may have existed a reluctance with Chinese teachers to show ‘outsiders’ their national, or personal martial arts, but others did not know the original intent of the art, and continued to spread the empty shell they were handed.

These factors helped contribute to the spread of misinformation, making it difficult to validate much of the material being practiced outside of the ‘standardized’ sets. The Chinese fighting arts were also fast approaching a century of existence without the practical combat usage of the fighting techniques housed inside the forms being transmitted as part of the art.

Without the trial by fire checks and balances that a martial fighting system uses to hold its validity; such as - 'fail to do this technique correctly and you get punched in the face, tossed on your head, or pushed off a platform' - an environment was effectuated that was ripe for esoteric practices, myth, and legend to take over. To include, but not limited to; mysticism, numerology, archaic medicine, fancy legends, mystical energy, and the most contagious of them all…pseudo-science.

While the combat effectiveness waned, the health benefits of modern taijiquan remain steadfast and clear. There have been many studies by qualified medical professionals around the world substantiating the health benefits of routine tai chi practice in one’s daily activities. However, these health benefits are not unique to tai chi, and may be attained through most almost any form of physical exercise such as, but not exclusive to - running, swimming, cycling, dance, tennis, raquetball, and numerous other sports.

There remains though, a primary advantage of tai chi over some, but by no means all other forms of exercise. A low-impact form of physical exercise accessible to those unable to perform rigorous exercise. This is especially important to senior citizens, or those with debilitating injuries who can benefit from movement, but are unable to participate in high impact sports mentioned above.

Modern tai chi, while no longer a martial art is a form of exercise or martial dance, that can be taught to people of all ages, allowing practitioners to move, think, and have fun as a social activity anywhere they go. Whether it be those looking to improve balance, circulation, stress reduction, bone strength, or those who think they are too old to work out, or too “out of shape” - all can find a welcome home in studying the soft styles of tai chi in its modern representation.

Conversely, if one is looking for a martial art for the purposes of practicing and perfecting methods of violence in its traditional sense, then the modern representations of tai chi, or taijiquan are likely not to be pursued.

What we can all stand to discard, are the esoteric pseudo-science methods transmitted by charlatans and those looking to manipulate others for financial gain, or illusions of power.

LEARN MORE…

If you enjoyed this article you may also find the following articles of interest -

Personal Quest

Alongside teaching tai chi movement for well over a decade, my thirst for the combat applications of these moves/forms overshadowed my ability to teach people without discussing, showing, demonstrating, and instructing people in the combat methods inside the tai chi forms as I unraveled them.

I realized, my goals and desires were no longer aligned with the middle aged, and senior audience that was partaking in my classes for the benefit of health and wellness. Rather than cause injury to people who were, intrigued, but not committed, conditioned, or enrolled for such a class, I amalgamated these combat methods into my mantis boxing classes so I could continue to teach them to a captive audience who is there for such knowledge and skill, and would like to put these into practice for their skill set.

While I retired from teaching tai chi for health and fitness in 2016, I remained steadfast in my quest to unlock these combat applications lost to the annals of time. If you would like a small glimpse of the results of decades of work in reverse engineering these amazing combat techniques that are half a century old, check out the following page to see videos of a few of the moves.

Tai Chi Underground - Project: Combat Methods

Bibliography

Wile, Douglas. T'ai-chi's Ancestors: The Making of an Internal Martial Art. New York: Sweet Ch'i, 1999. Print.

Kennedy, Brian, and Elizabeth Guo. Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic, 2005. Print.

Wile, Douglas. Lost Tʻai-chi Classics from the Late Chʻing Dynasty. Albany: State University of New York, 1996. Print.

Kang, Gewu. The Spring and Autumn of Chinese Martial Arts, 5000 Years = [Zhongguo Wu Shu Chun Qiu]. Santa Cruz, CA: Plum Pub., 1995. Print.

Smith, Robert W. Chinese Boxing: Masters and Methods. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1974. Print.

Fu, Zhongwen, and Louis Swaim. Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Berkeley, CA: Frog/Blue Snake, 2006. Print.