A Daemon in my Dojo

The afternoon sun turns to shadow early as the solar cycle wanes and we fast approach the winter solstice. I was finishing my training and sitting down to meditate when the visitor walked in.

A new visitor arrived in my dōjō today, a stranger from a far off land. It is the beginning of autumn in the year 2012. Dōjō, or ‘way place’ in Japanese, a place to study the way of ‘something’, typically martial arts. In Chinese martial arts we call it a wǔ guǎn (wǔshù guǎn), or martial hall, the place in which we gather for the study martial arts.

The afternoon sun turns to shadow early as the solar cycle wanes, and we fast approach the winter solstice. I was finishing my training and sitting down to meditate when the visitor walked in. Lately I have been consistently practicing meditation as a post training routine to clear the mind, to take inventory, and to stay grateful.

It has been thirteen years since I began practicing Praying Mantis Boxing (tángláng quán), and a bit over a year since undertaking the art of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (B.J.J.). I recently competed in my first BJJ competition as a newish white belt. Currently, I am training and coaching six days per week, as has been the case for the past eight years. When I’m not teaching or occasionally unfurling my wings to deftly dance off a cliff to reach for the clouds above, I pen articles on martial arts as thoughts and ideas materialize that may be of use for others on this path. I have been cross training in other arts for a few years, nothing serious prior to BJJ, but enough so that I have been experiencing modalities outside of Chinese boxing arts; seeing a broader picture.

I sit regulating my breathing, trying to focus my mind. A bright warm light washes over me as the door opens. The stranger interrupts with abrupt words that leap forth like a flash of briny sea water surging to shore on the rush of high tide. These noises flood my brain. At first I am annoyed at this intrusion, and try to ignore it for a moment of solitude. Then, I pause to listen to what he said to me.

As my mind churns over the information it feels as if this visitor is casting a bright spotlight into the deepest umbra in my brain. He begins to spout emphatically about Bēng Bù, crushing step for short, but the longer meaning is – steps to cause the enemy to collapse and fall into ruin. Bēng bù is a shadow boxing set found in styles of mantis boxing, I have been practicing this set since 2005 learning five or more versions from the various lines of mantis boxing, part of my quest to decipher the true intent behind the shadow boxing shell transmitted through mantis boxing lineages for the past one hundred years, or more. I’ve vigorously searched for the hand-to-hand combat applications originally intended by the creator(s), wanting my own continuation of this boxing style to be effective in fighting. Something I have rarely seen thus far.

Eventually I settled onto one version of bēng bù that I train a few times per week, occasionally spending time mulling over the potential applications within my head. The stranger's words snap like a bolt of lightning crackling through my mind. Riding along the spectrum of light his question crackles forth: “Why is bēng bù, like so many other Mantis Boxing forms, begun with and finished with the move, ‘Mantis Catches Cicada’?”, he continues on, “This is not a finishing move to end a fight, so why would this technique of all of them be laid out in form after form almost as bookends?”, “Is this just stylization? Is it a meaningful application?” His questions intrigue my mind, I begin chasing the lightning along its incongruous path.

Code breaking comes to mind, more specifically ciphers. I reply to the stranger, “A cipher used to crack open an ancient codex. A boxing form, in this case crushing step, a set of choreographed moves from a boxer of old, is this the codex and Mantis Catches Cicada the cipher? Perhaps this move is ‘the key’ to unlock the applications within the form?” I begin traversing the halls of the labyrinth in my mind, searching every corner, opening every door, looking at each move in bēng bù from a ‘two hooks’ (neck and arm, or colloquially known in fighting circles as a ‘clinch’ position.

The dialogue and the air around this impromptu visitor, ripple with electricity in the air. I struggle to keep pace with the trove of possibilities his questions raise. As I peruse the catalog of choreography in each road of the set, I conclude that some of the bēng bù boxing moves could certainly function from this position, but others clearly not. The questions then enter my mind, “Where is he from?”, “What, or who, is the source of visitors knowledge?”, “How did he happen upon my dojo?”. I asked his name. “Wang”, he replied.

Wang was a pesty guest, talking incessantly his entire visit. “Does he ever shut up?”, I wondered to myself silently. A wave of empathy washed over me, he did travel from afar, and spent so much time alone unable to talk to anyone about this subject matter. A topic that must be yearning to escape the prison of his mind.

Wang spoke day and night, following me home after classes. He had nowhere else to stay on his visit, I felt compelled to open my home to him, annoyed at times, but grateful for his illuminating thoughts and inquiries.

During his stay I rarely caught a wink of sleep. Wang sat next to my bed at night incessantly rambling till the sun came up. With no choice I lay awake listening to the chatter, staring at the ceiling, throwing off the sheets in exasperation, pacing the room, and spending nights shadow boxing while Wang rolled on. I caught a wink of shuteye here and there, only to rise early again the next day. A true insomniac, Wang did not sleep, obsessed with his ideas which spawned forth like seven hundred baby mantids hatching from an ootheca in the midsummer garden.

With seemingly nowhere else to be, Wang stayed for weeks, revealing a series of mantis boxing positions and hand-to-hand combat applications I had never considered before. I immediately went to task testing these in drills, sparring, and grappling as Wang sat looking on in satisfaction. A new world arose around me; a schism manifested, a cataclysmic shift in my worldview of fighting.

Wang, seeing my progress, bid me farewell for the time being, proclaiming as he exited my dojo, “Perhaps I’ll return, but for now, you need to chew for a while before we can dine again.” I bowed to Wang in gratitude, and wished him well on his travels. Thus concluded my first visit with the daemon who sojourned to my dojo.

Discovering the 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing

The above short story is an allegory based on real events. An episode in my life back in 2012 consiting of an explosion of ideas and thoughts. The dōjō is not the one I train and coach inside night after night, but rather the one I spend far more time in, the one inside my mind.

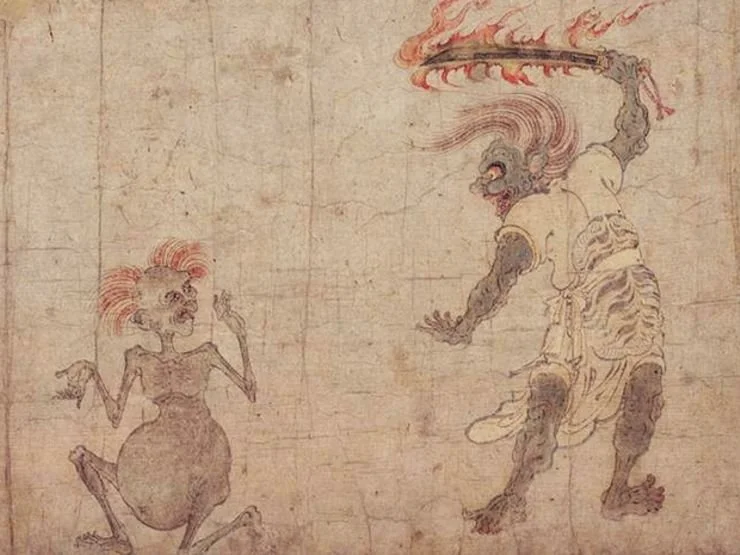

My daemon, Wang, is based on Wang Lang the mythical founder of mantis boxing. The man accredited with the origin of this boxing style hundreds, or thousands of years ago, depending on who you listen to. You can read more about Wang Lang in an article I wrote on his possible accreditation to the art here: The Apotheosis of Wang Lang

Prior to this experience I had little in the way of instruction or conversance with the 12 keywords of Mantis Boxing. I certainly knew of them, as most serious and long term practitioners of the art do, but I had yet to delve into them. From my observations and experiences any information regarding these keywords, and conversations surrounding them amongst mantis boxers and coaches, devolved into arguments over what the ‘correct’ keywords are, and their true meaning.

The thoughts I had on ‘mantis catches cicada’ were real. However, while this was a ground-breaking revelation that sparked an age of discovery, and helped lead me onto a fruitful path, years later I debunked this theory when my research exposed mantis catches cicada as nothing more than a — brand moniker, rather than an actual fighting technique. A mantis boxing en garde to proclaim, ‘We do mantis.’ This moment in time though, when all these thoughts began to appear, shifted my brain into thinking of each move from a whole new pillar of fighting — wrestling/grappling.

My daemon helped me to see the first three of the twelve keywords of mantis boxing with new eyes. I began to commit pen to paper, to record these thoughts as they manifested. It crawled from my pores with an unstoppable force. We took photos. I wrote my first quasi-article on ‘What is Praying Mantis Boxing’, now titled The Heart of the Mantis, a rough experience. This idea that wrestling was an integral part of mantis boxing was scoffed at by the mantis boxing community, and some were extremely rude in their rebuttals. I charged forth anyway, fully committed and stalwart in my belief that I was on the right path. As with any new endeavor, I was getting my legs under me as I awoke from a slumber.

Over the ensuing years Wang would come by for a visit from time to time. If I was not paying attention he would splash hot tea on my brain, burning me so I would once more bring my full attention to bear on what he had to say. As I continued boxing, grappling, and progressing in BJJ I unlocked more and more positions and fighting applications. An increasing number of the keywords unlocked before my eyes.

I noticed a similarity with other grappling arts and recalled Gichin Funakoshi remarking in his book Karate-Do that I read back in 1999, that Kara-Te (way of the Tang Hand) was a blend of techniques Okinawan nobles would bring home from southern China during the Tang dynasty, and blend them with their indigenous fighting arts. Years later finding out those indigenous arts were wrestling.

As we sat in the garden sipping tea on one of Wang’s visits, he asked me: “What were China’s indigenous fighting arts?” I began to delve into the history of the Chinese martial arts ecosystem as a whole, coming across...Bokh, the Mongolian wrestling arts still alive to this day. This was enlightening especially since many techniques looked similar to postures found within Mantis Boxing (and other styles) forms of Chinese martial arts that I had studied over the years, to include: taijiquan, eagle claw, long fist, and more.

Bokh, and its history/influence on Chinese culture when the Mongols invaded and took over China during the Yuan dynasty, made me grossly aware that Mantis Boxing along with other Northern Chinese Martial Arts styles that I had studied over the years, contained a great deal of stand-up grappling, or wrestling. This realization has evolved over time as my understanding has grown, now aware that the Manchu were heavily vested in wrestling culture, ruling China for over 250 years during the Qing dynasty; the last of the dynastic eras of China. From there a growing realization of Han wrestling, jacket and no jacket wrestling from the Shaanxi, Shanxi provinces, along with a broader understanding of how much wrestling was part and parcel to so many cultures the world over, almost integral to our DNA as a species.

I could now see that a bulk of these ‘systems’ from northern China seemed to revolve ‘around’ grappling as a primary pillar, using methods and tools to facilitate ways to clinch and grapple an opponent, to throw or trip them to the ground.

The other primary art I trained and taught at the time of writing the above essay, was Taijiquan, specifically Yang family style which was originally known as small cotton boxing. The principles within that style also screamed grappling and I began to dig into the 13 keywords of Taijiquan, performing a comparative analysis of mantis boxing and supreme ultimate boxing after finding so many parallels. This is a working document that I return to from time to time over the years - Brothers in Arms: Mantis Boxing versus Supreme Ultimate Boxing

Arriving at ‘my’ 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing

Hook, Clinch, and Pluck were the first lessons from Wang Lang. These were followed by Lean. Lean was particularly elusive at first simply because myself being a striker/kicker I failed to see why we would want to lean in a fight, only to give our opponent a shorter distance to hit us in the head. Once applied to grappling and the close distance fight, leaning becomes integral to our survival.

The other keywords were increasingly harder to unravel, with growing absences between visits from my daemon. Long arduous periods of contemplation and frustration, times where I would continue to ask questions into an endless vacant void. From time to time though, my daemon would once more return, once more shredding the thick overgrown vegetation of confusion with razor sharp claws.

Once I could see through the adeptly graven undergrowth, and light shine upon the darkness once more, new techniques would reveal themselves. Eventually, a keyword, or two, would whisper from the lips of my daemon and wisp through the tattered leaves in the garden.

Adhere was the next to become apparent, especially due to its significance in BJJ, where controlling, or consuming space from an enemy while grappling on the ground was so significant. The same was true in stand-up grappling.

Strike was not as simple as it seemed. Ultimately, it is simple ‘to hit’, but why would something so obvious be a keyword? My daemon laughed at me, “If you don’t strike as you Enter, you’ll meet your doom.” he said. “If you do not strike to Connect, you will fail to find your enemies limbs, and meet their fists as you arrive.” “If you do not strike in the clinch, be prepared to receive…injury!”, he laughed harder.

Connect & Stick were the next keywords to be codified. Wang Lang, ever the sarcastic ethereal daemon, made disgusting references to gum, saliva, and the various stages of sticking, to bring these epiphanies to life. “That’s the easy part, but knowing when and how to use them without being punished is another issue entirely.” Offensive application versus defensive utilization was worthy of deep study, otherwise a broken nose would ensue.

Beng, to collapse and Fall Into Ruin came to me in the garden one day. Wang Lang was hanging out on the branches of my kale plants attempting to capture unsuspecting wasps, butterflies, and bees. As his hook snapped out to strike an unsuspecting passerby, he did not crush this victim with his deft strike, but caused it to collapse and fold in upon itself, crumbling to the ground below.

Beng was such a loud lesson that I had to write an article for it and publish it in a magazine for all to see. The idea that causing the opponent to collapse and fall into ruin using various methods, was revelatory to say the least. Especially since one of the core forms of mantis uses this in its name.

Wicked, or in other words, to be ‘sly, deceitful, or tricky’. Wang Lang just flat out hit me over the head with a heavenly strike on this one. What is a fake, or feint when boxing, if not a ruse to open up the opponent and land a strike? A loud noise, bang, or yell - are they not a diversion to enrapture our opponent for a brief moment so that we may gain unfettered access to enter and annihilate them? The use of pluck to force an opponent in the opposing direction of our throw, trip, or takedown, gain freedom to adhere and lean as we barrel forth into a takedown; is that not beguiling?

Wang Lang was rather condescending on that last one, especially since I had been using these tools for years yet failed to see the connection to the keyword he left etched in history.

Hang was another slap on the head, or ‘duh’ moment. Hang was pointed out by my daemon genius spirit. He vaingloriously proclaimed to me - “If you don’t root, lower, ‘hang’ on your adversary when engaged with hooks in the clinch, you’ll get tossed and trampled like you tried to wrestle an elephant!!!”

The Keys to the Style? Or Keys to the Stylist?

The 12 keyword formula of Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳) houses the principles that help define the art. These characters, or variations of them, have been passed down through the common vernacular of Chinese boxing methods in northern China. While not unique to mantis boxing, and evidence of their existence in other styles of the region and time period exist, they can establish a definitive strategy for mantis boxers; much more so than a collection of tao lu (forms) that have no consistency from one branch of the style to the next.

Replication of these keywords does exist among the various lineages of mantis boxing, especially in the first few keywords. No matter the style, many of the more obvious in name keywords such as: Strike, Crush, Hook, Enter, Lean, Clinch, Pluck can be witnessed in Mantis Boxing forms. Those which are harder to mimic in the air - Connect, Stick, Adhere, Hang, and Wicked, are absent in the forms from all indications, and are found rather through live training and sparring practice.

Many of the grappling specific keywords exist in various forms of martial arts still alive today. Although lost within Mantis Boxing lines, one needs simply look at other unarmed combative styles to find evidence of not only their existence, but also significance when it comes to fighting.

An art, of any type, is not defined by hard and fast rules, but is open to interpretation and adaptation by the artist. Keywords of a style, or system of boxing, are a series of principles to guide the practitioner. The definition of these principles and what they mean is highly variable and intimately related to the boxer using and/or coaching them.

The keywords can change from boxer to boxer, allowing for wide adaptation and freedom of expression, and each boxer can select which they rely on more than others. As long as the boxer adheres to a loose framework which includes the hook and pluck keywords, as well as the connecting and sticking specifically, then the stylist is still manifesting an art which mimics the fighting traits of the praying mantis.

These 12 keywords I pass on represent the foundational core of my mantis boxing art. Which strikes, kicks, throws, trips, submissions, you choose to use when you fight can vary widely from my own. And yet, with common principles we bond together as martial artists, share, and reward one another’s successes.

It took me six years to unlock what these keywords mean to me. Use them to discover your own methods. Keep what is valuable to you, discard what is not. Practice with it, fight with it, and your own truth will be one day be revealed to you. Validity in martial arts is not established by the opinion of others, but rather it is, and should be, measured by the success of the actions and execution of our methods.

To learn more about my 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing you can find a course I have available that combines video instruction with more detail in written explanations and descriptions of each of the 12 keywords.

The Origins of Wang Lang of Tángláng Quán - 螳螂拳

Wang Lang (王朗) was a military folk hero/warlord in the Eastern Han dynasty (25CE - 220CE). Born in Tancheng County in the south of Shandong near the border of Jiangsu province. Wang Lang’s deeds are recorded and as with other famous figures in Chinese history, Wang was later memorialized and embellished upon in a famous novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. How did Wang Lang become entwined with the history of Praying Mantis Boxing (Tángláng Quán - 螳螂拳) almost 2 millenia later? Is this the same Wang Lang, or was there someone else who founded this boxing style who went by the same name?

Wang Lang (王朗) was a military folk hero/warlord in the Eastern Han dynasty (25CE - 220CE). Born in Tancheng County in the south of Shandong near the border of Jiangsu province. Wang Lang’s deeds are recorded and as with other famous figures in Chinese history, Wang was later memorialized and embellished upon in a famous novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Sacrificing to heaven and earth, the oath at the peach garden, Romance of the Three Kingdoms/Chapter 1 - An illustration of the book - From a Ming Dynasty edition of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (金陵萬卷樓刊本) , 1591 - the original is kept in the library holdings of Peking University 1591

Wang’s bio according to Chine.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

Wang Lang 王朗 (died 228 CE) courtesy name Jingxing 景興, was a high minister and Confucian scholar of the early years of the Wei period. He came from Tan 郯 in the commandery of Donghai 東海 (today's Tancheng 郯城, Shandong) and was, as proficient in the Confucian Classics, appointed gentleman of the interior (langzhong 郎中), then magistrate of Ziqiu 菑丘. In the turmoils of the Yellow Turban rebellion 黃巾起義 he became a follower of the warlord Tao Qian 陶謙, who promoted his appointment as governor (taishou 太守) of the commandery of Guiji 會稽. This region was contested, and Wang Lang had to ward off the warlord Sun Ce 孫策. The warlord Cao Cao 曹操 therefore decided to offer him the post of Grand Master of Remonstrance (jianyi dafu 諫議大夫), and made him concurrently military administrator of the Ministry of Works (can sikong junshi 參司空軍事). When Cao Cao, as factual regent of the empire, was made king of Wei 魏, Wang Lang was made governor of Weijun 魏郡 and "military libationer" (? jun jijiu 軍祭酒), later promoted to Chamberlain for the Palace Revenues (shaofu 少府), Chamberlain for Ceremonials (fengchang 奉常) and Chamberlain for Law Enforcement (dali 大理). When Cao Pi 曹丕 (Emperor Wen of Wei 魏文帝, r. 220-226) assumed the title of emperor, Wang Lang was appointed Censor-in-chief (yushi dafu 御史大夫) and given the title of neighbourhood marquis of Anling 安陵亭侯. Somewhat later he was made Minister of Works (sikong 司空) and promoted to Marquis of Leping Village 樂平鄉侯. Emperor Ming 魏明帝 (r. 226-239 CE) conferred upon him the title of Marquis of Lanling 蘭陵侯 and appointed him Minister of Education (situ 司徒). His posthumous title was Marquis Cheng 蘭陵成侯. Wang Lang wrote commentaries to the Classics Chunqiu 春秋, Xiaojing 孝經 and Zhouguan 周官 (Zhouli 周禮), and wrote numerous memorials to the throne. Most of his writings are lost.

Sources: Zhang Shunhui 張舜徽 (ed. 1992), Sanguozhi cidian 三國志辭典 (Jinan: Shandong jiaoyu chubanshe), p. 36. Ulrich Theobald Copyright 2016

In Romance of the Three Kingdoms Wang Lang

In the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Wang Lang died at the age of 76 in 228. Despite his age, he led a group of soldiers and set up camp to do battle with Zhuge Liang. In the novel, Cao Zhen was defeated by Zhuge Liang. Cao Zhen called for his subordinates to help, and Wang Lang decided to try and persuade him to surrender (even though Guo Huai was sceptical that it would succeed) and engaged Zhuge Liang in a debate, but was soundly defeated. Zhuge Liang among other things scolded him as a dog and a traitor, from the shock of which he fell off his horse and died on the spot. There is no record of this in history, and instead, it is said that he merely sent a letter to Zhuge Liang recommending that he surrender. The letter was ignored.

Luo, Guanzhong (14th century). Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Yanyi)

The Apotheosis of Wang Lang (王朗)

The birth of mantis boxing has been well debated. Some claim it was a product of the Song dynasty (960–1279), while others place it in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The evidence however points to the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) as the likely period of birth, and Wang Lang is a contributing factor to the evidence.

How did Wang Lang become entwined with the history of Praying Mantis Boxing (Tángláng Quán - 螳螂拳) almost 2 millennia later? Is this the same Wang Lang, or was there someone else who founded this boxing style who went by the same name? I believe these are one and the same.

Wang, as with many famous generals in Chinese history, was deified. He became a god especially to those villagers and communities in the region near his birth. There is even a statue of Wang Lang located in Shandong province. There is however no mention in historical records of Wang Lang practicing or teaching something known as - praying mantis boxing. Wang existed long before mantis boxing appeared in the second half of the Qing dynasty. So how did Wang become the progenitor of this style in the 18th or more likely, the 19th century? Who incorporated Wang Lang into the mantis lineage, and why?

Was it Wang Rong Sheng (王榮生, 1854-1926) founder of the ‘seven star’ branch of praying mantis boxing? Even though Rongsheng had a different teacher (Li San Jian, also not a mantis boxer) than the other mantis boxers under Liang Xuexiang? Wang Rongsheng’s shared surname with the famous deity is likely a mere coincidence. Perhaps Wang Rongsheng’s family lineage tree did trace all the way back to the Han dynasty warlord. This is all conjecture. It is unknown who tied Wang Lang to Tanglangquan's history, but the time period can be narrowed down by other cultural factors which existed in Shandong province in the late 19th century, and from these a reasonable explanation of how this connection was made can be discerned.

Shen Quan

During the 1800’s boxers were highly prevalent in Shandong. Some were tied to religious sects, and mini uprisings, others to banditry. Most just trying to survive. Some were even recruited at times to fight the religious groups such as The White Lotus, and other sects. Foreign imports, and factories took many of the jobs in the cotton weaving industry Shandong was known for. A large portion of the population became unemployed, and economically depressed. Treaty ports such as Yantai (where mantis boxing was born), were affected even more by this foreign incursion of industry and lifestyle. This by proxy, caused a rise in banditry.

A mid-Qing (1700’s) emergence of Shen Quan (Spirit Boxing) in Shandong, whereby the practitioners recited incantations, danced wildly, and believed they had been possessed by a spirit/god that gave them courage, and even invulnerability, reappeared in the late 1800’s as the Boxer Uprising was beginning in full. The original founder of Shen Quan believed he had been possessed by a famous Tang dynasty general he knew from an opera. This same spirit-boxing was repopularized in Shandong during the late Qing when the region was collapsing economically and had been pummeled by droughts, famines, drug addiction, banditry, wars, and rebellions. A perhaps misguided means of ‘self’ control by villagers and peasants to pray for rain, or turn their deities ire toward their Manchu rulers, and later the western invaders.

At this time opera and folklore was highly popularized in local villages, towns. Famous stories were acted out such as Water Margin, Journey to the West, The Enfeoffment of the Gods, and The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Wang Lang’s exploits were part of these tales, and Wang was a hero that would have had personal meaning to the locals of Shandong as he hailed from their homeland.

Joseph W. Esherick explains:

“most north China villages had a small temple to the local God (Tu-di shen), or perhaps to Guan Gong.”

Additionally, Esherick writes:

“There was one paramount occasion when these temples became a focus for community activity: the temple fair, held annually at temples in larger villages or market towns. The name for these - “inviting the gods to a performance” (ying-shen sai hui). The center of attention was an opera, for the benefits of the gods.”

It important to capture this in the entirety of what Esherick writes next:

“Above all, these occasions were welcomed for the relief they provided from the dull monotony of peasant toil. Relatives would gather from surrounding villages. Booths would be set up to sell food and drink, and provide for gambling. The crowds and opera created an air of excitement welcome to all. But the statement of community identity provided by opera and temple was also extremely important. It is important, too, that the gods were not only part of the audience: many of the most popular dramatic characters---borrowed from novels which blended history and fantasy---had also found places in the popular religious pantheon. Since few villages had resident priests, and few peasants received religious instruction at larger urban temples, it was principally these operas that provided substantive images for a Chinese peasant’s religious universe. This is why sectarian borrowing from popular theatre is so important. To the extent that sectarian groups incorporated gods of the theatre, they brought themselves into the religious community of the village---rather than setting themselves apart as a separate congregation of the elect.

The importance of village opera for an understanding of the Boxer origins can hardly be overstated. As we shall see below, the gods by which the Boxers were possessed were all borrowed from these operas. That many of the possessing gods were military figures is hardly accidental. From what little we know of the operas of west Shandong, it is clear that those with martial themes, for example those based on novels Water Margin, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and The Efeoffment of the Gods were particularly popular. This is to be expected given the popularity of the martial arts in the area, but it no doubt helped that Jiang Zi-ya (Jiang Taigong), the hero-general sent down from heaven to assist the founder of the Zhou dynasty in The Efeoffment of the Gods, was himself supposedly enfeoffed in the north Shandong state of Qi, and the heroes of Water Margin made their base in the western part of the province.

In many ways it was the social drama of the theatre which tied together elements of popular culture most relevant to the rise of the Boxers. Here was the affirmation of the community which the Boxers sought to protect. Here were the martial heroes who expressed and embodied the values of the young martial artists of this region. Here were the gods by which the Boxers were possessed---gods now shared by sectarians and non-sectarians alike. When the young boxers were possessed by these gods, they acted out their battles for righteousness and honor just as surely as did the performers on the stage.”

Was Wang Rong Sheng spirit boxing with the deity Wang Lang? Was it one of his friends, Jiang, Song, or Hao, the founders of the other branches of mantis boxing (plum blossom praying mantis boxing, supreme ultimate praying mantis boxing, supreme ultimate plum blossom praying mantis boxing) that emerged around this time? All of them acting together perhaps? Or was this something their teacher Liang Xuexiang being wiser, older, educated, and well traveled used to inspire the younger boxers under his charge?

Esherick continues”

“The martial artists that we have seen in the mid-Qing (Li Bingxiao for example) were men whose social world was outside the village community. Many led wandering lives as salt smugglers, peddlers, or professional escorts; others were primarily associated with the gambling and petty crime of market towns.”

Later in the Qing, Escherick points out, this changed as banditry became more prevalent. At this time young men were more often studying martial arts for self-defense, and protecting their communities and families. There was a movement toward community defensive efforts, and in more agrarian areas, crop defense.

Whatever the reasons for Wang Lang being assigned attributions as the creator of praying mantis boxing we can most likely determine from the popularity of spirit boxing and the trend in the late 1800’s that this period in time during the late Qing, when shen-quan was revitalized, was the period when Wang was incorporated into the lineage. We can view this same occurrence in Eagle Claw Boxing around the same time period to the northwest in Hebei province. Yue Fei, another famous general in Chinese history is credited with founding that style. Yue Fei also had no definitive connection to eagle claw boxing prior to this time period in the Qing.

In the second generation of the lineage charts in both mantis boxing and eagle claw, are similarly obscured. In both styles there is no definitive link between the founder and the next verified carrier of the torch. The two have very similar discrepancies within their histories after these deities supposedly invented them. The oral records claim the styles after being invented, then went into the Shaolin temple almost 900km (560 miles) to the west, and three to four weeks walking distance away from Yantai where mantis existed centuries later. There is no known record of mantis, or eagle claw styles being part of the Shaolin boxing system. Are we to believe these styles, if they did exist at Shaolin for a time, were suddenly spit back out hundreds of years later back in Shandong or Hebei?

It is much more plausible that these military legends, Yue Fei, and Wang Lang, were brought about into these styles in the late Qing as spirit boxing rose to prominence once more amongst the martial artists of the time. As we’ll see in the time period of Li Bingxiao (李炳霄 1731-1813 estimated), during the ‘High Qing’, martial artists did not stay with one teacher. They rather learned from a multitude of sources similar to a modern day university student, thus making it extremely difficult for the concept of ‘styles’ to gain root during this time unlike a few decades later.

This can explain the lack of history in between the founders, and the verifiable practitioners of these arts in the late Qing. Why they suddenly ‘disappear’ into temples in their lineage charts. Only to then reappear centuries later with traceable roots. It explains an oral history in mantis boxing that this style was an amalgamation of 18 different ‘styles’. This is far more believable and easier to comprehend in the realm of martial arts if each of these 18 ‘styles’ was a technique or two from each independent source the practitioner learned from. Finally, it can further explain why prior to the 18th and 19th century, there is no definable lineage for these arts.

Bibliography

Esherick, Joseph W. The Origins of the Boxer Uprising. University of California Press, 1987

ChinaKnowledge.de An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art, edited by Ulrich Theobald - Sanguozhi 三國志(www.chinaknowledge.de), Wang Lang 王朗(www.chinaknowledge.de)

Luo, Guanzhong (14th century). Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Yanyi)

You can purchase these books on my Amazon store and help fund research like this.

The Origins of the Boxer Uprising - https://amzn.to/3c3iz36

Romance of the Three Kingdoms vol. 1 - https://amzn.to/2McZZKT

Romance of the Three Kingdoms vol. 2 - https://amzn.to/3sOIZM0

Romance of the Three Kingdoms vol. 3 - https://amzn.to/3sW5wXl