Form vs. Function: A Lesson in How to Get Worse at Martial Arts

Fifty. That's the number of kung fu forms I had accumulated after 7 years of training. This was a combination of empty hand and weapon forms from a myriad of Chinese boxing styles. Some of you reading this, may think this is somehow a great achievement; I found it disparaging and detrimental to my martial arts training. Something that led to a decline in my skills, and ability to run/teach a new school with eager students.

Forms are choreographed sequences of martial movements. In Karate they are call kata. In wu shu (aka - kung fu) they are called tao lu. Historically forms were used as a database to store a boxers martial arts techniques. A way to practice techniques when one did not have a partner available to train with.

Why were forms used in traditional Asian martial arts, and why do we not see them in boxing, muay thai, judo, wrestling, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, etc.?

A majority of the population in China and surrounding areas were illiterate. There were no videos, photos, etc. for people to pass on information. These choreographed sets were at times used as a method of transmission from one boxer to another, or as a storehouse for a boxers arsenal of hand-to-hand, or weapon combat methods.

Forms were also used for thousands of years in China, as callisthenics training for troops, or intimidation of an enemy army prior to engagement on the battlefield. Forms have a long, deep history in Chinese martial ritual/training, and are often for this reason, difficult for practitioners to separate their importance, or lack thereof, from the true underlying point - the practice of methods of violence.

This factor has played into why Chinese martial arts has gone off the rails in an extremely destructive train wreck. Function became absent from forms, and forms became the pedestal in which one’s art was judged. Like judging the quality of a significant other based on their make-up they wear, or their clothing, rather than who they are as a person.

After 7 years of training in Chinese martial arts, I had little practical knowledge of the kung fu applications locked within these forms. My only exposure to ‘real’ methods of attack and defense, were routine uncoached sparring, often way too hard and fast to be productive at anything other than hurting one another, and joint locking (qin na), which I trained as an entirely separate component from the normal class schedule.

I had zero idea what the moves inside my forms were designed to do. Additionally, I could barely keep 20 forms fresh in my head without having to run back to the video documentation I would compile so that I could keep records of what I had learned.

As far as handling myself in a fight after all this training? If I am honest about it, I would say on a good day, I could have handled myself against the average joe, but against a knowledgeable trained fighter? No chance. This was upsetting too me, and continued to gnaw deep in my bones as years passed, especially after all the hard work and countless hours of training I had done. What was the point? I wanted to know how to fight, not dance.

Whenever we would spar in classes, there was no cohesion of any kind between applications in the forms, and our fighting. Again, they seemed to exist independently of one another, with any sort of homeostasis lacking. It is as if one had absolutely nothing to do with the other. I began to question everything I had been doing. I stared long and hard into my art, and myself. Years before I had studied tae kwon do and found it lacking. I sought out kung fu 'specifically', so I could be a badass martial arts fighter. That was not happening.

Another growing problem with collecting forms - the more of them I learned, the worse I actually became at martial arts. Even though my mistakes were aplenty in the first years of training, as I progressed ever closer to competing in Nationals, I felt that my abilities and precision with my forms grew markedly worse than it was in year 1.5 to 2 years into training. Even when I won two gold medals and a silver at Nationals, I felt scattered, all over the map, and certainly unable to allocate enough time and focus on any one thing to master it.

This frustration caused me to look for answers through the annals of history. As I scrolled through text, after text, I recognized a pattern - zero, or limited numbers of forms to each style. Nowhere in the history of these Chinese boxing styles did I see 50 forms, 30 forms, and certainly not 125 forms which some boast about in their curricula. Instead, I found at their roots - ba gua: 1 form; tai chi: 0 forms; eagle claw: 3 forms; praying mantis boxing: 2, maybe 3 forms depending on who you talk to. Xing yi: 0 forms, Hung gar: 1 form.

This was a significant revelation to me at the time, and I began to recognize the gaping flaw in my own training practices. Immediately I started throwing away forms I did not want. Show forms, acrobatic forms, and anything that seemed too contrary to the other forms I decided to keep. I also began researching the styles of kung fu that were of most interest to me, as I had encountered and practiced many at this point. These included - mantis boxing, eagle claw, long fist, southern fist, hung gar, tai chi, and over 17 types of Chinese weapons.

It had come down to this - ‘I had to narrow my focus’. I chose praying mantis (my original style) and tai chi. I kept tai chi only because the two were so similar to one another that I was able to focus on both in tandem. Following this pruning of the tree of knowledge, I sought out experts in those prospective styles to fill in the gaps years of misspent training had created.

That training ultimately served me well in the long run, but I could not help but feel discouraged and somewhat angry about all the time I had spent chasing these trivial, or ephemeral things I thought were going to make me better. I felt like Gollum in The Hobbit, or Lord of the Rings, ever chasing the ‘shiny precious’s’ down every crevasse of Mordor imaginable.

Eventually I found people with the knowledge that I truly sought, and the know-how to show me how to do what I enjoy most - breaking things apart and figuring out how they work. With this knowledge I have been able to reconnect the past to the present and have a new found appreciation for forms and the depth of knowledge that they often hold.

It’s amazing how many of the true fighting applications have been lost from Chinese boxing arts. But now, it is easy for me to understand why. If we took a string of 10 BJJ moves that we would apply based on our attacks, defense, and the opponent countering, and we then remove our partner, we have a form. A BJJ form.

If I took said form and taught that to a student, but did not show the application to each move, yet I was precise and particular about each detail being correct and just so, ensuring the individual were handed something that would work if needed, two things would result:

They wouldn't be able to use it for real, and…

After I taught them and was no longer watching over them, they would change something through forgetfulness, laziness, or just plain desire to do a move differently than the way it was originally taught.

Now that same student teaches that form to someone else. What happens then…? The fighting application is lost. Possibly for good, if no one else is carrying it on. One generation. Lost. That is all it takes.

Without function, a form is just an empty shell subject to the flaw of human transmission. It reminds us of the game telephone. Where people sit in a circle and one person whispers in the next persons ear, and each person is supposed to repeat it around the circle until it comes back to the originator. It is never the same sentence.

So ultimately, form should always match function, and function should be realistic and achievable in full speed all out combat. This keeps integrity in the system, and keeps our martial arts honest.

If we are in a style with forms, how many is the right number? I would counter with - how many applications do you need in your style? An average form in Chinese boxing has 30 to 50 moves in it. If the form is a specialization set, e.g., its primary mission is kicks, then it may be lacking when it comes to offense/defense in a real fight.

If the forms is a boxers arsenal, then it will likely contain strikes, kicks, throws, and counters that they considered their primary method of fighting.

How many forms do you need in a 'forms-based’ format? If you only do forms, and do not practice how to use the techniques inside, how many forms/routines can you remember, or reasonably practice before seeing your skills drop. This is completely arbitrary, but for me, when my training had a heavy forms focus, 3 to 5 was plenty.

In 2004 when I traveled to Pennsylvania for the Nationals Qualifiers, I had three forms I competed with. Once I qualified, I decided for Nationals I was going to compete with 5 forms. This expansion was a mistake. Although I did well in the two of the three divisions I competed in at qualifiers, the other sets suffered. I had less polish on them.

If you practice forms, and you know each of the applications, consider testing these on a live and resistant partner(s) to keep the applications intact as intended. Making sure they can stand up to someone throwing multiple punches not just stepping in and throwing one strike.

If you have no idea what your forms do, but you want to learn:

If possible, seek out good teachers in your style that might know the answers. This saves you time/energy of reinventing the wheel.

If that is not an option, then find a martial art based in real technique such as boxing, kickboxing, muay thai, jiu-jitsu, judo, wrestling, shuai jiao, sumo, etc. This way you can have a solid self-defense system to accompany your forms.

If your style is multi-faceted, take up boxing for a while to learn more about hands, upper body, positioning, and footwork. Kickboxing, muay thai, or silat for kicking power, and skills. Take up judo or shuai jaio to learn throws, trips, takedowns. Wrestling, and/or BJJ for grappling experience. Learning BJJ has helped me unlock so much more understanding of my mantis boxing.

Above all else - SPAR! Not point sparring either. Test your skills and you will have invaluable lessons to help you weed out bad techniques from the good.

Size Matters - In Qín Ná (擒拿)

“Having spent years studying these locks, I found it awkward to pull some of them off in 'live' situations. A great many of them if attempted, would have landed the practitioner in a world of hurt from their opponent. Simply from the person reacting by punching them with their free hand/arm. This article attempts to clarify some of the misunderstanding of how and why Qín Ná does, or does not work.” - Excerpt from an article published in the Journal of 7 Star Mantis Volume 3, Issue 3 on the Chinese Joint Locking method known as Chin Na, or Qín Ná (Capture and Seize 擒拿).

Why Qín Ná works, and does not work.

Original article can be found here

Qín Ná (Capture and Seize 擒拿) - the Chinese art of bone and joint locking found in many styles of Kung Fu including Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳).

The human body has a plethora of ways that it will, and will not bend. Qín Ná capitalizes on these anatomical weaknesses with the objective of controlling, or destroying one's opponent. Locks exist for every joint, from the head to the toes; and quite possibly 20 to 50 variations of each one depending on who you talk to, or what reference you use.

Having spent years studying these locks, I found it awkward to pull some of them off in 'live' situations. A great many of them if attempted, would have landed the practitioner in a world of hurt from their opponent. Simply from the person reacting by punching them with their free hand/arm. This article attempts to clarify some of the misunderstanding of how and why Qín Ná does, or does not work.

qīng Dynasty and Republican Era

Much of the documentation I have been able to find on Qín Ná, comes from the late Qīng Dynasty (late 1800's when China's Martial Arts practice was in decline), and the Republican Era; with some emerging during the Communist reign.

These sources are often littered with a ridiculous amount of locks; and include locks that are completely irrelevant to fighting. I recall one technique involving a hair grab from the front - the victim is attempting a forward hand press lock with no leverage to counter the attacker grabbing hair on the front of his head. A simple counter-attack to the persons groin would suffice, yet here lies an ineffective lock.

Forms - Our Window to the Past

Forms are perhaps our oldest and most reliable documentation of Kung Fu's history of techniques. They are our library or catalog of applications that are relevant to each system or style. Given the lack of documentation on Chinese Martial Arts through the ages, we have to rely on forms as our window to the past.

If you look at the majority of Kung Fu forms they are comprised of strikes (fists, elbows, knees), kicks, throws, and locks. The locks however, typically focus on gross motor movements; attacking the most accessible joints - elbow, shoulder, hip, and knee. Earlier in my training I studied close to 25 to 35 hand forms, and rarely, if ever, have I found a small binding lock within those forms.

Motor Function and Stress

The primary reason Qín Ná often fails to work, or has no place in certain situations, is our motor function skills. According to the National Police Association the level of accuracy in gun fights across the nation was reported at 12% for 2008. These are individuals that train to use their weapons over and over; yet there is a problem hitting their targets when under intense pressure; proving we as human beings lack accuracy and fine motor skills under stressful situations.

In the world of Qín Ná - humans in the midst of situations such as physical altercations, use gross motor function and react with adrenaline coursing through their system; the heart rate is up, breathing becomes erratic, palms sweat. These factors alter the reality of trying to attempt a finite lock on someone as they attack; grabbing a hand out of mid air becomes increasingly difficult.

Training the same technique over and over through repetition, helps eliminate this problem, but only if the training approaches live scenarios in it's charter.

In essence, if the locks are simply practiced with compliant partners, and/or in fixed sequences such as line training, then we will find them unreliable in combat. To counter this, we can train the locks with 'feeder drills' that lead to random sparring to increase effectiveness.

Size

The where, when, and on who, of locks is the most crucial element of lock training. What we cannot recover from, is attempting a lock on a larger and stronger opponent when we tried to use the wrong lock on them. This is typically where we get punished trying to use joint locks.

A human body, is a human body; no matter what size the person is. Aside from certain individuals who are double jointed, locks will work no matter how big the person is. The problem isn't whether a joint will lock, the problem is, a larger person also has larger muscles.

It becomes increasingly more difficult to manipulate these larger muscles when we are a smaller fighter. We need the appropriate strength to turn and position the joint, and then apply the lock. The battle becomes strength on strength, instead of technique winning the day.

As an analogy - joint locks will work on animals just as they will work on people, but you will see drastically different results if you attempt a lock on a dog vs. a horse. The two animals are not only different sizes and weights, but possess far different strength potentials. 12 dogs to pull a sled vs. 1 horse to pull a wagon. In the human world of Qín Ná, there is no difference. If you attempt a lock on a much larger opponent, they will resist with strength and then counter with a punch, grab, or counter lock.

Working with different sized partners can give us insight and kinisthetic feedback to this phenomenon. Learning to move from compliant to resistant training will train us on how to detect, and become sensitive to, the when and where of applying locks; so that when we meet someone that resists, we know automatically to switch to another lock, or resume striking to soften the target.

Target Fixation

Military and civilian pilots have a term - 'Target Fixation'. For a military aviator it is most prevalent when we are diving and attacking a ground target. We become so fixated on our target, we fail to realize our altitude reduction, and leave insufficient time to pull the aircraft out of the dive - thereby crashing into the target itself, or the ground.

This same principle applies to joint locks. It is a common occurrence when we train Qín Ná in fixed patterns, to get lock fixation. As we attempt a lock, and the initial attempt fails, we become fixated on making the lock work. We continue attempting to apply the lock while our opponent is at first resisting, and then changing position; then starting to hit us, throw us, or reverse the lock.

We can avoid these situations by dynamic lock training, or principle based lock training. Instead of opponent throws X punch or Y grab, we train the principles of locking by themselves; direction, fulcrum, refined technique. Then once we have an understanding of these, apply feeder drills to train dynamic locking and counter locking.

In this type of training, opponent attacks, we counter and apply X lock, and our opponent resists and/or applies Y counter, and then we can apply our counter. The lock, the counter, and the counter to the counter, so each of us learns to move fluidly from one joint lock technique to another, or even transition back to striking.

Since fighting is random, it only makes sense for us to recreate this randomness in our training without full on fighting. If we try to apply in sparring, stress will take over and we operate in survival mode rather than learning mode.

Small vs. Large Binds

We can narrow locks down to two major categories:

- Large Binds - locks attacking major joints such as the elbow, shoulder, knee, ankle.

- Small Binds - locks that attack small joints such as the wrist, fingers, toes.

The key is for us to know when and where to use each of these locks. Given that stress is involved in a live situation, and as previously stated, gross motor function is more likely - large binds should be used for initial contact. The larger joints take larger motions, which fits into our first response to an aggressive act. Gross movement is more reliable and quite possibly why we see these in the Kung Fu Fighting Forms and a lack of small binding locks.

Small binds are more appropriately used when we are responding to a grab, in the clinch, on the ground, or finishing the opponent after softening them up with a throw. When we are tied up (grappling) with an opponent and have access to the occasional finger, toe; wrist, or ankle, then small binds are extremely effective. After we have thrown the opponent and they are stunned, we have access to time and movements that were otherwise difficult to pull off and can score a small bind as well if appropriate.

Leg Locks

Leg Locks are effective when we are able to pull them off; keeping in mind that the legs are proportionally stronger than the upper body of a human being. When we are attempting to lock up an opponents legs, we are fighting strength, maneuverability, and multiple weapons - other foot/leg, arms.

These are best attempted after a throw, or when our opponent is least expecting it - such as rolling in a ground fight. Basic knee bars can be applied as a counter to a kick, but attempting to maintain the lock on the ground after you have tripped them, is foolhardy at best. Our arms alone lack the strength to keep their knee from bending, and once they bend it, they will be more than willing to use their fists on our head.

I mention these due to our applications of trapping a kick and trying to apply a leg lock in the air. This works to effect a takedown, but enters problems when trying to maintain that lock on the ground without using larger parts of our body as the fulcrum and lever such as the hips or torso.

In conclusion, Qín Ná is a highly effective and rich part of our art and can be of great benefit. Training and practicing with appropriate measure is crucial to success, as well as understanding when it is appropriate to use each lock. We are wise to avoid the over complication that is commonly seen in much of the reference material on Qín Ná. Seek out the K.I.S.S. method (Keep It Simple Stupid) when locking and you will find success.

The Truth on Effective Strike

Effective Strike (Xiao Da), is the Chinese principle of striking to vital targets, or targets that have more destructive impact than other areas of the body. This is a common concept in many styles of martial arts. I recall the first time I showed up for Tae Kwon Do/Hapkido class back in 1991 - my teacher said - "Want to kill a man? Hit here, here, here, or here." I was happy, but stunned.

reprint of an article published in 2013 in the Journal of Seven Star Praying Mantis -

Xiao Da - The Truth on Effective Strike (Journal of 7 Star Mantis vol. 4, issue 4/Northern Shaolin Praying Mantis Institute and Association 2013)

Targets

Listed below are the targets and the effects a person experiences when being hit in those regions.

8 Head Targets

Throat

Side of Neck

Back of Neck

Jaw

Nose

Eyes

Ears

Temple

12 Body Targets

Shin

Knee

Outer Thigh

Inner Thigh

Groin

Bladder

Rib (Floater)

Kidney

Liver

Stomach

Solar Plexus

Collar Bone

Photos courtesy of Max Kotchouro

Cervical Spin - Downward Elbow Strike

Effective Strike (Xiao Da), is the Chinese principle of striking to vital targets, or targets that have more destructive impact than other areas of the body. This is a common concept in many styles of martial arts. I recall the first time I showed up for Tae Kwon Do/Hapkido class back in 1991 - my teacher said - "Want to kill a man? Hit here, here, here, or here." I was happy, but stunned.

I thought to myself - "WOW! Cool!!!" Followed by - "wait...why would you tell someone that in their first class? Isn't that dangerous information to hand out to strangers? After all even US Army Basic Training Hand to Hand Combat didn't teach us that!". I chalked it up to him just being half psychopath since he spent most of his life training elite South Korean Special Forces Soldiers in Hand-to-Hand Combat.

It was some time later in my martial arts career that I realized why this information wasn't so dangerous after all. The reason is simple. If you don't train it, you won't use it. Effective Strike is a skill like any other. It needs extensive practice and proper training in order to be effective in real combat, or in other words - to manifest itself under stress. In said Tae Kwon Do class, we never used finger strikes, throat chops, or did any sort of training that incorporated strikes to these vital areas; we simply kicked, punched (less), blocked, and smashed our shins and forearms on one another till bruised an battered.

Brachial Stun using Slant Chop

Train Like You Fight, Fight Like You Train

I like to use the terminology - train like you fight, fight like you train. In your Kung Fu training, the constant focus of hitting to Effective Strike targets is crucial to making this habitual. There is no time to think in a fight. One must react and react appropriately; which is the whole objective of proper training.

So when should you learn this skill? Ideally the sooner the better, especially for smaller fighters. Smaller fighters lack the power that a larger or heavier opponent can produce, so this skill is crucial for us. Being able to hit someone in a targeted area means that your strikes pack more bang for the buck.

With that said, one needs to learn how to properly punch first, before focusing on Effective Strike. Trying to perform Xiao Da from Day One, gives the brain too much to focus on at one time. A beginner should be more concerned with proper striking, blocking, guard principle, and defense first. Once Xiao Da is properly introduced, aim for these targets with every strike in your arsenal.

After you have learned it, you can then veer off to other non-effective targets that may lure or distract your opponent; creating what we call Open Doors to the effective targets we want. This is necessary because an opponent with a good defense will 'require' you to 'open doors' in order to hit his covered targets.

Training Tips

These vary based on whether or not you have a training partner. I did not have a partner to use when I wanted to integrate this into my fighting, so I took colored price stickers used in yard sales, and I plastered them on my heavy bag in the general target areas on the human body. I then practiced various combinations striking to these targets. To test them, I sparred with other people.

For those with a partner, I recommend a great technique called 'Walk the Body', passed down to me from a mantis boxing coach on the west coast. Walk the Body has one person standing still (in their fighting stance is fine) while the other practices slow and very low power combinations to targets on their partners body.

As you grow more comfortable with the targets, the complexity increases by having your partner put their hands up in a defensive fighting position forcing you to move their arms. Following that, you need striking combinations, that the partner blocks, so you can open doors to the Effective Strike targets you wish to hit using solid striking combinations.

Note: this is not a fast paced exercise and requires patience, cooperation, and hours of practice to become second nature. It challenges your critical thinking skills once you add the complexity of combinations versus a live defense. Done properly however these strikes will become automatic and ingrained in your skill set.

Ear Claw

DIM MAK - The fallacy of pressure point based combat

Early in my training I met people, and still do from time to time, that have little knowledge of martial arts, but they talk about Dim Mak (pressure point striking) from books they've read, or videos they've watched, or even some Hollywood movie.

You can find videos online of teachers knocking out students at demonstrations to show Dim Mak, and all the supposed power one can have over other human beings by hitting them in these targets. People are fascinated by this and very enthusiastic. I can understand why, the idea of knocking out someone else with such ease is...alluring! Unfortunately, while some of these are legitimate strikes to real targets, some are incredibly finite and difficult to get to.

In a previous article, Size Matters - In Chin Na I discuss 'gross' versus 'fine' motor function in combat. Just like finite Chin Na skills, high precision striking is less reliable when we are under stress, AND when our opponent is trying to hit us back. That's the live, active, and moving opponent that is also trying to ‘take your head off’ component.

This complicates things and makes it much more difficult to perform a finite strike to a small target area. So unless you're Luke Skywalker firing your torpedo at the Death Star, give up on the idea, and stick with something that will work.

Natural armor - in addition, a human being under the affects of adrenaline in combat (never mind the affects of drugs), is more resilient to these strikes. It really sucks when you're in the thick of it and your silver bullet doesn't really kill the werewolf! This is why it is better to learn multiple targets, strike in combinations that you would normally throw, and cover your bases in case you miss the first target. Meaning, you missed but it still hurts them like hell!!!

Targets Defined

Temple Strike using Backfist

8 Head Targets

Throat - Crush the larynx making it difficult to impossible for opponent to breathe

Side of Neck (Brachial Stun) - Knock out blow, or excrutiating pain at the least

Back of Neck (Occipital Lobe) - Knock out blow

Jaw - Break or Dislocation. Extreme pain.

Nose - Pain. Bleeding. Watery Eyes causing reduced vision.

Eyes - Loss of sight. Extreme pain.

Ears - Tear them off for extreme pain.

Temple - Knock out blow. Extreme pain. Disorientation.

Knee Break using Cross Kick

12 Body Targets

Shin - Extreme pain and discomfort.

Knee - Break/Dislocation. Extreme pain. Loss of Mobility.

Outer Thigh - A solid kick to this target can cripple a fighter and make them think twice about closing distance.

Inner Thigh (Femoral Nerve) - Identical to the Outer Thigh, this target causes excruciating pain.

Groin - Extreme pain and discomfort. Potentially cripple opponent.

Bladder - Pain and discomfort. Possible bladder release. (you figure it out)

Rib (Floater) - Break. Extreme pain and discomfort. Possible breathing effects.

Kidney - Potential knock out as well as extreme pain.

Liver - Knock out blow. Extreme pain/discomfort.

Stomach - Knock out blow. Extreme pain/discomfort.

Solar Plexus - High concentration of nerves. Also the meeting point of the heart, liver.

Collar Bone - Break. Extreme pain. Loss of use of arm on that side. Harder target to hit and not effective on everyone.

Southpaw and The Crazy Ghost Fist

There is a long history of ancient cultures including the Greeks, Romans, and Chinese, that prejudice left-handed use, or left-handed people. It is seen as - sinister, wicked, evil, and many of the words for such are derived from the word left in these languages.

In Chinese culture, the major philosophies and religions believe in the universe spinning from left to right; things must always start on the left and move toward the right to remain in harmony. This is expressed in many of the Traditional…

There is a long history of ancient cultures including the Greeks, Romans, and Chinese, that prejudice left-handed use, or left-handed people. It is seen as - sinister, wicked, evil, and many of the words for such are derived from the word left in these languages.

In Chinese culture, the major philosophies and religions believe in the universe spinning from left to right; things must always start on the left and move toward the right to remain in harmony. This is expressed in many of the Traditional Kung Fu forms that we see and is heavily documented in Tai Chi manuals. The symbol for Yin Yang depicts this cycle as well.

In stand-up martial arts - a majority of boxers place their left foot forward in fighting, just as a majority of baseball players stand on the left side of the plate at bat. By and large, right-hand dominant people outnumber left-hand dominant people, but this does not give cause to ignore the significance of this change of position when faced with a 'southpaw'.

The term 'southpaw' is typically used to define a left-handed boxer. A fighting position, or stance where one fighter has their right foot forward versus the traditional pose of the left foot forward used by right-handed boxers. Of more interest to us, are the advantages and disadvantages of this opposing, or unorthodox stance.

Why Staggered and not Square

Before we discuss that, let's hammer out why someone stands one foot in front of the other in the first place.

A squared up stance in hand-to-hand combatives can be good from a power based perspective. You give equal power to both arms, as well as equal reach. Some self-defense systems teach this at their core. The cost however outweighs the benefit.

Being square is something you can be successful with in martial arts such as Wrestling, Shuāi Jiāo, or Judo; striking arts change the game. The square position exposes our centerline to our opponent, giving access to vital targets on our body such as the solar plexus, liver, bladder, groin. These can be game-over strikes if they land on us.

By taking up a staggered stance and slanting the upper body, what we call 'blading', we decrease our profile (smaller target), but strikes are more easily deflected off the angle of the body, protecting these sensitive targets. An opponent is then required to circle to the inside line in order to access our centerline. This is easily read by veteran boxers.

Southpaw

In a staggered stance where both fighters are aware of the advantages and disadvantages of being square versus bladed, there is another, deeper component that becomes a major liability - when one fighter is on the opposite foot.

Meaning, boxer A has their left foot forward, and boxer B has their right foot forward - this is where southpaw becomes the challenge. Here are some of the pros and cons to the southpaw position:

Pros of Southpaw

- Easier to attack the flank - kidneys, ribs, temple, ear, and occipital lobe, brachial nerve; all exposed from outside angle.

- Cuts off the opponents second hand from attacking when on the outside line.

- Sets up significant number of trips, sweeps, take-downs.

- If dominant hand is forward - offers a stronger jab stunning the opponent.

- If on the inside line, it squares up the opponent, offering clear shots with the power hand to solid vital targets. in the face and body.

- Exposes the opponents groin to attacks with kicks, grabs, strikes, knees.

Cons of Southpaw

- When on the inside line we are in reach of both hands and susceptible to attacks not normally possible when directly in front of your opponent.

- Opponent can attack our flank hitting vital or destructive targets.

- Groin is exposed to kicks.

- Legs are side by side if opponent is on our inside line, making us more vulnerable to double leg takedowns, crashing tide, leg wraps, etc.

- Fighting southpaw allows our opponent to sweep our foot when we shuffle in, and if we circle to their inside, we are walking right into their power punch.

- This position also affects 'our' own range; placing the forward punch closer to our opponent, yet keeping our reverse punch so far away that it is often too far, or awkward to throw unless the other person makes a mistake.

Training Habits

In training, it is common to fight one-sided. In other words people choose a side to train and often ignore the other side, giving it less attention. In these formats a righty will spend most of their time fighting other righty's, while a lefty, or southpaw, will spend most of their time fighting righty's. This gives the lefty an advantage over the righty. They spend a far more time in this position and are then able to develop superior tactics and strategies from such.

Be aware of this tendency, and train diligently to overcome this challenge by putting yourself in weaker positions on purpose. This will allow you to adapt to this change and be hypersensitive to it in sparring/fighting.

Know your weaknesses and capitalize on your gains

What to do on the outside line

If you are on the outside you want to remain there if possible, providing you have the correct angle. In this position you should be lighting up your opponent with hooks to the head, ribs, and kidney while attacking the inside line with your other hand using effective combinations.

Look for throws that work from here. Side Leg Scoop, and Tiger Tail Throw, Reaping Leg are all obvious choices.

What to do on the inside line

- Strike up the middle high and low while being aware of any position changes made by your opponent that may put you at risk.

- Kick or Punch to the groin.

- Attack with Double Leg Takedown.

The Crazy Ghost Fist of Mantis Boxing

Mantis Boxing's Crazy Ghost Fist - The first move in the core form known as Bēng Bù (Crushing Step 崩步). This move is a perfect example of proper use of the southpaw position.

Our opponent punches. We move to the outside line while blocking the arm and striking the ribs/liver with a reverse punch.

Check out this video on how it's applied.

Southpaw can be a great advantage, or a horrible liability depending on your skill level and how you use it. As a rule, when I teach beginners I leave it out.

It's more important to understand the basic orthodox stance first, and change stance with the opponent in the early stages. This keeps your blocking system intact. Once a boxer is comfortable with this position, then we begin to explore the Southpaw advantage.

Bridging - How to Close Distance in a Fight

You charge in on your enemy, filled with the hope that you can capitalize on that weak spot you spy in their guard. As you are about to land your punch, suddenly, without warning, BAM!!!! POW!!!! SMACK!!! His strike has met you mid-stride and square in the nose. As blood begins to rush down your face you pause and wonder, why you were unable to hit that giant hole that invited you to enter to begin with?

"You charge in, filled with the hope that you can capitalize on that opening you spy in their guard. As you are about to land your punch, suddenly, without warning, BAM!!!! POW!!!! SMACK!!! A strike has met you mid-stride and square in the nose. As blood begins to rush down your face you pause and wonder...'Why was I unable to hit that giant hole that was wide open, and they were able to hit me'?"

If you have fighting experience then you are likely all too familiar with the above scenario. After countless bouts, sparring matches, fights, most of us have found tricks of the trade that allow moderate success at gaining the advantage as we move in on our opponent (bridge).

Alternatively, some have decided to become counter-fighters, and instead of risking the in-fortuitous disaster, patiently await their opponents charge knowing full well the advantage will be their's.

To help avoid circumstances such as these, here are some solid tactics to incorporate into your training so that you may gain control over this most unsure of moments in fighting; the moment when you go from out of range, to in range. The moment we call - 'bridging'.

The following are a few definitions:

'Bridging' - the act of moving from outside of striking or kicking

range to inside striking or kicking range.

'Critical Distance' - The line that separates the two ranges. Critical Distance is determined by the range just outside the reach of your opponents longest weapon - their rear leg.

'Bridging Tactic' - a method of occupying the enemies mind, body, or both, so that they are unable to move or launch a counter attack the moment you cross the 'Critical Distance' line.

As we explained in above scenario - the danger with bridging is vulnerability when moving or transitioning. Timing (another bridging method) works in this regard. If you are in the midst of steaming headlong into your opponent's waiting defense, while preoccupied with striking, then you are vulnerable. The solution is to incorporate Bridging Tactics into your fighting toolkit to give you the advantage.

Here are some examples for executing an advantageous bridge:

Overwhelm

These tactics involve rushing style attacks that overwhelm the opponent.

Pi Quan

Circle and Chop

Beatdown Chop

Chopping Fist Advance

Flying

Flying Palm

Mandarin Duck Kick

Other

Sān sài bù - 3 Section Step

Distractions

Distractions rely on proper timing to execute. These can vary and you can certainly add more to this list. Here are the primary ones we cover.

Fake Leg Attack Hand

Flag Hand

Smack Hands

Experienced practitioners will also focus on more advanced bridging methods such as:

Feints*

Fakes*

Hiding Motion in Motion

Range Manipulation

*Note: according to veteran coach I worked with, that had been in many fights, these bridging methods have less of a chance of working on people in a street fight situation, who have never been hit. They do not respond as expected because there is no correlation of the fake attack with the actual end result.

Feint

A body movement that simulates a move or shift in one direction while then moving in another direction. This works as a great precursor to an attack when used at the proper range. As the enemy flinches, plants, or reacts in some regard, they are locked into their movement and unable to react to the real attack that immediately follows the lie.

Example on how to Feint-

Pretend to move left with your body and then quickly move right. When your opponent moves to gain advantage or reposition themselves for defense they create openings in their guard. Strike the targets now available, or shoot for the takedown on the exposed side.

Common Pitfalls -

Body movement is jerky and unrealistic. Opponent doesn't believe it.

Feinting, and then moving in the same direction you feinted. This gives your opponent warning of where you are going to move and nullifies the tactic.

Fake

A false strike that triggers the opponents block or counter. Again, as the opponent flinches, you immediately follow the flinch with your real strike to a different target.

Example -

Throw a forward punch (jab) but do not follow through with it. Done properly the opponent should emit a jerk-type response and attempt to block the non-existent punch. More experienced fighter's may resist the temptation, but may blink or twitch instead. Immediately strike the opponent in a different target right after they jerk, blink, or twitch.

Common Pitfalls -

If there is too much of a time break between the fake and the real attack the opponent will have reset and snag the actual strike.

If you try to attack the same target as the fake attack then the opponent will likely block because their hand is already in that region and they previously witnessed an attack to that target a split second before, so they are now expecting a real one.

The fake doesn't look real. You have to sell the fake, as if it is the real deal, without over exposing the limb for them to grab, or seize.

Distraction

An act of motion, sound, or use of surroundings that will trigger a response from your opponent; causing them to momentarily flinch or become distracted.

Example on how to Distract-

Make a loud noise by yelling, stomping, or banging your gloves together. Upon witnessing your opponents twitch immediately bridge and enter past the critical distance and attack. In a street situation, the distraction may be throwing an item such as keys, coins, sand, or an object.

Common Pitfalls -

Too quiet, or not convincing.

Too much lag time between the distraction and the bridge.

You have tried it too many times without following up with a live attack. The opponent is not appropriately conditioned to it and will not respond, making them dangerous if you try to enter.

When bridging, the tactic either works, or does not work. This is immediately determined by whether or not they blocked your attack, moved out of range, or sprawled before you got there. If unsuccessful, the bridging tactic needs to be corrected or refined by training your ability to perform a realistic fake or feint so your partner believes the lie.

Range Manipulation

To be continued...

The Dirty History of Tai Chi

The history of Tai Chi, correctly called Tai Ji Quan, disseminated to the masses, is often a mythical story that involves an art form thousands of years old with Taoist immortals, monks, and fairies. Commonly it is propagated that a non-existent type of magical energy, will heal the practitioners body and/or throw opponents without ever touching them. This is a fictional portrayal that in the West we call a fairy tale and in the East they call wu xia.

The history of Tai Chi (taijiquan, supreme ultimate boxing) is often taken with too much salt. The prevalent history disseminated to the masses often involves a mythical backstory thousands of years old, which includes: Taoist immortals, monks, and fairies. It is commonly propagated that the style of Tai Chi contains and revolves around a type of magical energy (known as qi) that will heal the practitioners body and/or throw opponents, without ever touching them. This fictional portrayal in the west would be known as a fairy tale, in China it is called ‘wǔ xiá’ (武侠), martial arts stories in theater/fiction popularized during early 1900’s China.

The notion that one can achieve unequivocal power, something akin to a superhero, without ever performing a day of ‘rigorous’ training, exertion, or hard work, is certainly the stuff of movies, myth, and legend. In contrast, the truth of tai chi’s history is far less enchanting to the laymen dabbling in an exotic art. The truth involves laborious acts, physical exercise, redundant practice, mental endurance, self-discipline, perseverance, and a history full of bloodshed, violence, and oppression.

General Qi Jiguang. Source: Wikimedia

The more accurate and verifiable history at the time of this writing shows that tai chi was developed roughly 400 years ago in Chen Village, Henan Province, China. It was known as less formally as ‘Cannon Boxing’, or the Chen family style. Like many Chinese martial arts it included hand-to-hand combat techniques common to the region, area, and time period. In 1560, General Qi Jiguang developed an unarmed combat system to train a militia to fight the wokou pirates. A group of Japanese pirates, which included Chinese ex-soldiers, privateers, and ruffians were pillaging the coastal villages and sea traffic. Based on the chapter in Qi Jiguang’s manual on unarmed combat, and the included illustrations, it appears by the trained eye that many of the depicted hand-to-hand combat methods are found in what is now known as tai chi. This points to a common pool of knowledge of fighting techniques.

During the mid 1800's Yang style tai chi was created by founder Yang Lu Chan. Yang, lived and studied in Chen Village and later went on to create his own system originally called 'Small Cotton Boxing'. Now known as Yang style tai chi, or taijiquan.

While many of Yang’s techniques mirror the Chen family boxing style, Yang included some of his own methods and merged them with the techniques of the Chen style, as any fighter will do throughout their martial journey when introduced to effective combat methods that they wish to amalgamate into their own art.

Yang’s life (1799 - 1872), or the life around him, was no stranger to violence and upheaval. Throughout his adult life he bore witness, knowingly, or unknowingly, to the impending collapse of China’s final dynasty, the Qing (1636-1912). Events happening all around Yang during his life include catastrophic flooding of the Yellow River (Huang He) (1851 - 1855, and many many more), famines, droughts, drug epidemics, two wars with the west (see Opium Wars 1839-1842, and 1856-1860), multiple rebellions (see Nian rebellion 1851-1868 and Taiping rebellion 1850-1864), and the encroachment of western powers on the Chinese populace, especially in and around trade ports.

As a result of losing both of the aforementioned wars, China was forced through treaty to pay reparations to the western powers, mainly by opening previously closed trade ports in the south and the north.

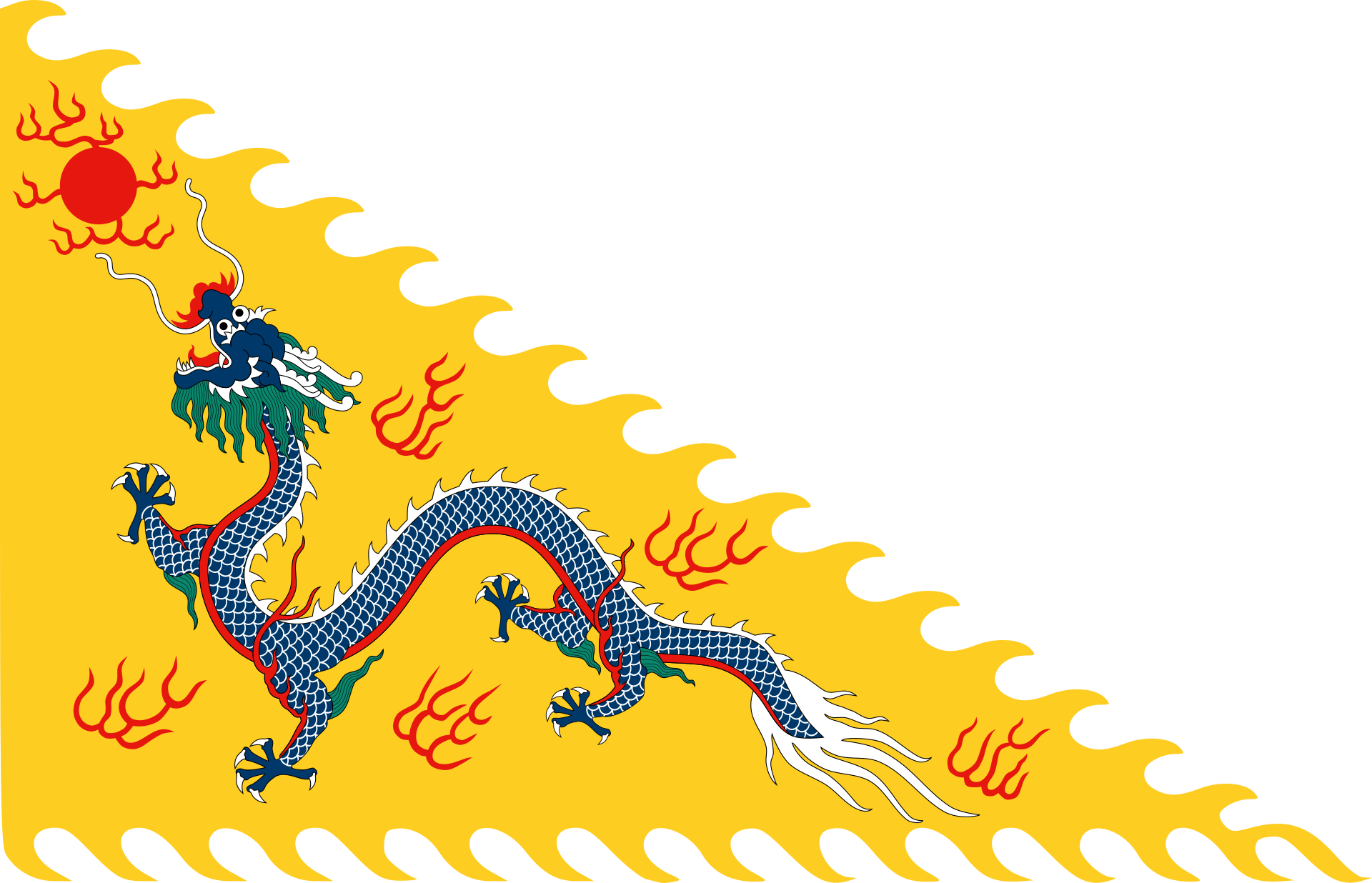

Imperial Standard of the Qing Emporer

Yang Lu Chan at one point in his life is recorded as being hired by the Qing court to teach armed, and unarmed combat to the imperial guards of the Manchu court in Beijing. Yang also disseminated his boxing art to his family.

Around the turn of the 20th century, decades after Yang’s death, the Chinese became disenchanted with their martial arts after repeated embarrassment in their confrontations with the west. More specifically incidents involving armed and unarmed combatants known as boxers, versus soldiers with firearms. Arguably the most famous of these incidents is known as the 'Boxer Rebellion', or more accurately the ‘Boxer Uprising’ (Joseph W. Esherick - The Boxer Uprising), which transpired over a four year time period with various encounters. The uprisings took place in Shandong, Hebei, and Tianjin provinces, as well as Beijing itself.

Port of Chefoo circa 1878 to 1880. Edward Bangs Drew family album of photographs of China, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Historical Photographs of China - https://hpcbristol.net/visual/Hv37-02

A century prior to this China was one of the most powerful civilizations on earth, with one of the most formidable military forces in existence. However, the industrial age in the west brought substantial change to warfare, along with the ability for nations to project global power in greater magnitude than ever before.

Although martial arts was considered beneath the scholar class, it was prevalent with boxers, soldiers, and guards in the employ of biaoju (security-escort companies). Local militia-men, sanctioned by magistrates commonly used armed/unarmed martial arts methods to quell local bandits and keep the peace. The Qing government in the 1800’s was preoccupied and impotent to respond to many smaller internal issues. The lowest expression of martial arts was associated with criminals, gangsters, ruffians, or charlatans which the Jing Wu and early 1900’s Chinese martial arts community tried to erase, or reverse.

The ‘boxers vs firearm’, or rather, antiquated military tactics versus modernized, industrialized weapons and strategies incidents that took place around 1900, likely further cemented the general public’s poor opinion of their nations martial arts, and of the ‘boxer’ overall. Three hundred years prior during the Ming dynasty General Qi, in his second book, published two decades after the first and post wokou battles experience, considered the act of training troops in hand-to-hand combat a rather fruitless endeavor when compared to the rapid and effective weapons training such a spears and matchlocks. This is evident since his second book omitted the unarmed combat chapter altogether.

Battle of Lafang 1900. Source: https://pin.it/5uubzq3xry77n5, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By the turn of the 18th to 19th century the Chinese having battled the western power’s sponsored opium crisis, repeated mass famines, floods, droughts that killed millions of people; rebellions that also killed millions more, and in addition to disease epidemics, were being called the 'sick men of Asia' by the international community. For a culture that was once in the not to distant past, more powerful than any other nation on earth this was humiliation on an epic scale.

At the end of the Qing (1910’s) and the beginning of the Republican era, a movement was initiated to change this stigma. A nationalist effort was undertaken to strengthen the populace and remove this cultural blight, or poor reputation. As a part of this movement and perhaps in an effort to keep their national arts from dying, Chinese martial arts teachers were commissioned to teach their methods for health, strengthening, and fitness, rather than for fighting.

This saw the creation of organizations such as the Jing Wu Athletics Association (circa 1910) of which tai chi, specifically Yang style, was a significant part of, as well as later the Nanjing Central Guoshu Institute in 1928. The directive of Jing Wu was primarily to improve health, and combat the 'sick men of Asia' label. Teaching physical fitness and health to affect positive national change. The Nanjing Guoshu Institute also propagated Chinese martial arts, and employed none other than Yang Chengfu, grandson to the progenitor of the style.

Yang Cheng Fu clearly had an entrepreneurial spirit that would help proliferate not only the Yang family art, but by proxy their predecessor, the Chen family, as well as the Yang offshoots of Wu family style Taijiquan, and Wu Hao style. Yang Chengfu took his grandfathers boxing art and taught far and wide, spreading it to the general public for health and wellness purposes around 1911.

Chengfu incorporated slow motion practice and longer movements as the focal point, removing much of the fighting application and combative elements taught by his grandfather, father, brother, and uncle. Thus was born a form of exercise that was all at once accessible to the young, old, weak, sick, and those of poor physical condition; to which rigorous exercise was not possible.

Prior to this Yang family taijiquan was taught strictly for combat, or a method of violence, or rather, defending against violence. It involved such skills as striking, throws, trips, takedowns, joint locks, sparring, fighting, and weapons training.

Forms practice (tào lù 套路), and push hands (tuī shǒu 推手) in contrast to present day, were likely a very small portion of the training. It is questionable if push hands had a significant role in the traditional combative training outside of skill building. It is possible that this portion of the training was derivative of the scholar class slumming in the martial arts world years after the art lost its teeth. A ‘game’ for people uninterested in fighting to pretend they are fighting.

It is also possible that given the heavy focus of the Manchu on wrestling, which was significant with the Han as well, that push hands was a tool for training wrestling skills in said competitions. The strategy of pushing an enemy in battle is ludicrous unless pushing them to the ground, or off a cliff. However, pushing someone outside a ring, or off a platform (lei tai matches) in order to score points, or win, holds a great deal of validity.

Qianlong Emporer observing wrestling match. Source: WikiCommons

Due to Yang Chengfu's efforts, and others around him, Yang style went on to become extremely popular, the most widely proliferated form of taijiquan throughout the world even to this day. The style’s true nature however is evident by some writers of the time:

Gu Liuxin writes of Yang Shaohou (Yang Cheng Fu’s older brother 1862-1930)

He used, “a high frame with lively steps, movements gathered up small, alternating between fast and slow, hard and crisp fajin (power/energy), with sudden shouts, eyes glaring brightly, flashing like lightning, a cold smile and cunning expression. There were sounds of “heng and ha”, and an intimidating demeanor. The special characteristics of Shaohou’s art were: using soft to overcome hard, utilization of sticking and following, victorious fajin, and utilization of shaking pushes. Among his hand methods were: knocking, pecking, grasping and rending, dividing tendons, breaking bones, attacking vital points, closing off, pressing the pulse, interrupting the pulse. His methods of moving energy were: sticking/following, shaking, and connecting.”

1949 Taiyuan battle finished. Source: WikiCommons

Three decades after Chengfu’s popular introduction of this rebranded art to the people, the Communist Party took control of China. As in past rebellions and changeovers of power, they once again outlawed the instruction of martial arts for the purposes of fighting. Mao Zedong, ever a student of history was well aware of the number of uprisings, rebellions, and dynastic turnovers associated with temples, and boxers. He burned the temples and banned the boxers.

During this period in the mid twentieth century, many traditional martial artists fled the country or were killed. The restriction by the government was certainly not in fear of a boxer, spearman, or swordsman attacking a tank, or machine gun nest, but rather due to a need to control the populace, a task exponentially more difficult when it involves submitting those trained in fighting arts (disenfranchised privateers, aka pirates). Martial training empowers individuals and empowered people are less willing to blindly succumb to oppression.

In 1958 after the period of unrest during the Communist Revolution (circa 1946 to 1949), China formed a committee of martial arts teachers. Choosing from a pool of those who stayed behind and used their martial arts training for coaching health/fitness, and/or those who had returned to the mainland from their exile.

The committee created what are known as the ‘standardized wushu sets’ - choreographed forms of shadow boxing summarizing and abbreviating the broad spectrum of China's legacy martial arts styles.

The wushu committee created the standardized sets for unarmed and armed styles, streamlining hundreds of styles in the north, and south that shared common techniques into one compulsory set to represent each - long fist (changquan) for the north, and southern fist (nanquan) for the south. In this consolidation effort, a few styles were left to stand alone gaining independent representation. These were, praying mantis boxing (tanglangquan), eagle claw boxing (yingzhaoquan), form intent boxing (xingyiquan), 8 trigrams boxing (baguaquan), and supreme ultimate boxing (taijiquan). Coincidentally these five styles were the advanced curriculae of the Jing Wu athletic association. Had they not been part of Jing Wu, it would be interesting to know if they would have survive long enough to be recognized by the PRC Wushu Committee.

These choreographed sets were then presented to the rest of world in a neat clean package, government regulated, and used to project China’s human martial prowess abroad, to include a trip to the Nixon White House where they demonstrated their skills. These boxing sets left behind the fighting elements of old, replacing them with sharp anatomical lines, clean corners, fancy acrobatics, and gymnastics. They became martial dance with 'timed' routines rather than the violent methods they once were.

As part of this standardization process in the 1950’s, the Yang taijiquan 24 movement form (a.k.a. Beijing Short Form) was created, and not by the Yang family itself oddly enough. This form represented Yang Style taijiquan (against the families approval) and went on to not only be a competition set, but a ‘national exercise’ that Chinese citizens would practice every morning in local parks for decades to come.

As China opened her doors to the rest of the world, westerners glimpsed the large organized gatherings of Chinese citizens performing their beautiful practice of the short form in parks day after day. Foreigners began learning this art while spending time overseas and via teachers who migrated to western countries proliferating their ‘art’ through hobby, or as a means of financial survival. The western world's interest was officially piqued.

Throughout the 1960's-70's and even into the 1980's, there may have existed a reluctance with Chinese teachers to show ‘outsiders’ their national, or personal martial arts, but others did not know the original intent of the art, and continued to spread the empty shell they were handed.

These factors helped contribute to the spread of misinformation, making it difficult to validate much of the material being practiced outside of the ‘standardized’ sets. The Chinese fighting arts were also fast approaching a century of existence without the practical combat usage of the fighting techniques housed inside the forms being transmitted as part of the art.

Without the trial by fire checks and balances that a martial fighting system uses to hold its validity; such as - 'fail to do this technique correctly and you get punched in the face, tossed on your head, or pushed off a platform' - an environment was effectuated that was ripe for esoteric practices, myth, and legend to take over. To include, but not limited to; mysticism, numerology, archaic medicine, fancy legends, mystical energy, and the most contagious of them all…pseudo-science.

While the combat effectiveness waned, the health benefits of modern taijiquan remain steadfast and clear. There have been many studies by qualified medical professionals around the world substantiating the health benefits of routine tai chi practice in one’s daily activities. However, these health benefits are not unique to tai chi, and may be attained through most almost any form of physical exercise such as, but not exclusive to - running, swimming, cycling, dance, tennis, raquetball, and numerous other sports.

There remains though, a primary advantage of tai chi over some, but by no means all other forms of exercise. A low-impact form of physical exercise accessible to those unable to perform rigorous exercise. This is especially important to senior citizens, or those with debilitating injuries who can benefit from movement, but are unable to participate in high impact sports mentioned above.

Modern tai chi, while no longer a martial art is a form of exercise or martial dance, that can be taught to people of all ages, allowing practitioners to move, think, and have fun as a social activity anywhere they go. Whether it be those looking to improve balance, circulation, stress reduction, bone strength, or those who think they are too old to work out, or too “out of shape” - all can find a welcome home in studying the soft styles of tai chi in its modern representation.

Conversely, if one is looking for a martial art for the purposes of practicing and perfecting methods of violence in its traditional sense, then the modern representations of tai chi, or taijiquan are likely not to be pursued.

What we can all stand to discard, are the esoteric pseudo-science methods transmitted by charlatans and those looking to manipulate others for financial gain, or illusions of power.

LEARN MORE…

If you enjoyed this article you may also find the following articles of interest -

Personal Quest

Alongside teaching tai chi movement for well over a decade, my thirst for the combat applications of these moves/forms overshadowed my ability to teach people without discussing, showing, demonstrating, and instructing people in the combat methods inside the tai chi forms as I unraveled them.

I realized, my goals and desires were no longer aligned with the middle aged, and senior audience that was partaking in my classes for the benefit of health and wellness. Rather than cause injury to people who were, intrigued, but not committed, conditioned, or enrolled for such a class, I amalgamated these combat methods into my mantis boxing classes so I could continue to teach them to a captive audience who is there for such knowledge and skill, and would like to put these into practice for their skill set.

While I retired from teaching tai chi for health and fitness in 2016, I remained steadfast in my quest to unlock these combat applications lost to the annals of time. If you would like a small glimpse of the results of decades of work in reverse engineering these amazing combat techniques that are half a century old, check out the following page to see videos of a few of the moves.

Tai Chi Underground - Project: Combat Methods

Bibliography

Wile, Douglas. T'ai-chi's Ancestors: The Making of an Internal Martial Art. New York: Sweet Ch'i, 1999. Print.

Kennedy, Brian, and Elizabeth Guo. Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic, 2005. Print.

Wile, Douglas. Lost Tʻai-chi Classics from the Late Chʻing Dynasty. Albany: State University of New York, 1996. Print.

Kang, Gewu. The Spring and Autumn of Chinese Martial Arts, 5000 Years = [Zhongguo Wu Shu Chun Qiu]. Santa Cruz, CA: Plum Pub., 1995. Print.

Smith, Robert W. Chinese Boxing: Masters and Methods. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1974. Print.

Fu, Zhongwen, and Louis Swaim. Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Berkeley, CA: Frog/Blue Snake, 2006. Print.