"What Style of Mantis Boxing Do You Do?" - Answering your questions...

I get this question from all of you on my YouTube channel quite frequently - "What style of Mantis Boxing do I practice/teach?" Seven Star, Tai Ji (Supreme Ultimate), Plum Blossom, Supreme Ultimate Plum Blossom, 6 Harmony, 8 Step, Wah Lum? I decided to take some time to answer you instead of leaving a quick comment when you ask. Hope this helps.

The 'Mantis Hand' was simply a 'Mantis Brand'

What has become abundantly clear to me through the research for my book on Mantis Boxing; along with the discovery and extrapolation of more and more techniques from within the forms, as well as the examination of the historical data surrounding the collapse of a dynastic period of a major civilization in world history, is the following…

photos by Max Kotchouro

Suggested Reading:

Prior to reading these notes below, I recommend reading my research notes leading up to this point. It will help you lay context for my observations and findings.

Research Notes: To Dissect a Mantis

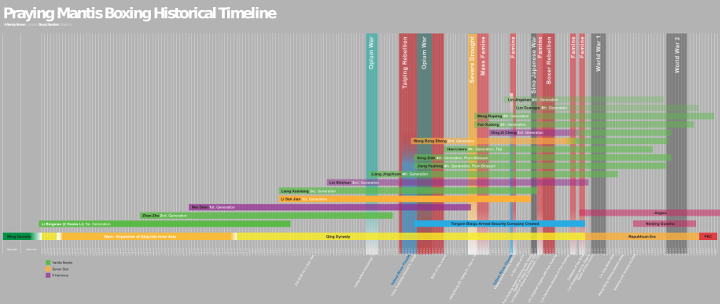

Research Tool: Mantis Boxing Historical Timeline

Notes

What has become abundantly clear to me through the research I’ve been undertaking on Mantis Boxing; along with the discovery and extrapolation of more and more techniques from within the forms, as well as the examination of the historical data surrounding the collapse of a dynastic period of a major civilization in world history, is the following -

Mantis boxing as we know it today, the versions of the style passed down to us for the past 120 years, is fake.

Mantis hand posture as depicted in a myriad of forms in Praying Mantis Boxing.

Now that I have your attention, allow me to explain. Fake is a strong word, and intentionally bombastic on my part. It carries with it a harsh connotation especially when it comes to an art that is held so dear to so many loyal followers. Present company included.

Fake, implies deception on the part of those teaching or partaking in the practice of it today. This...is anything but the truth. Without those teachers, practitioners, stewards of the art, who have carried this broken and hollow skeleton forward through time, we would not have any hope of a future for this art, or perhaps even Chinese boxing as a whole. To them, we owe everything. So what do I mean then when I use the word ‘fake’?

The idea that tanglangquan had some ‘special’ technique(s) never seen in any other Chinese boxing, or martial arts style in the world, is unrealistic, fantastical, or…fake. Almost all of the ‘real’ applications (and there are many), that come out of the forms, are absolutely amazing and effective combat methods. Methods that are alive in martial art styles today; including the remaining functional Chinese art, shuai jiao, and it’s progenitor from the Steppes peoples to the north - bokh.

A majority of the forms practiced by the various lines of praying mantis boxing were created after the turn of the 20th century. They are not combative forms. They are not even made by people who necessarily knew how to fight with mantis. This is evidenced by photographs we have of said people that began documenting the art in the first half of the 1900’s.

Photo of application of Wicked Knee depicted in one of many of Huang Han Xun’s books on Mantis Boxing. Technique found in mantis forms such as Seven Star Mantis’ Beng Bu (Crushing Step). Why is he standing on one leg? Why is his opponent holding his fists at his waist?

Wicked knee depicted in a mantis boxing form.

Note: I did not say, these practitioners could not fight. I am saying, that they did not fight with mantis. As is evidenced by the photo representations of the applications depicted in their books (see Huang Han Xun’s manuals for examples). Therefore, if some of the forms are choreographed by people that did not know how to use the moves within, then they are ‘fake’ martial arts.

If the forms contain applications common to the Chinese boxing methods of the time (1800’s), and offer nothing unique that sets the mantis ‘style’ apart, then the forms cannot be what defines mantis as being mantis. The keywords and their integration into a fighter’s combat methods could however, define what it means to be a mantis boxer.

The ‘mantis hand’ itself, is fake. This is unfortunate, as it’s rather unique and extraordinary, but it is the harsh truth. It is nothing short of branding. Marketing, as I explained at Chapman University in the Martial Arts Studies talk that I gave. The fingers curling under (as seen above) are incapable of grabbing effectively, and offer no distinct advantage in fighting. As a matter of fact, it offers a plethora of liabilities.

Unfortunately, this hand posture has confused generations of worthy and dedicated practitioners of the art. Myself included. A fleeting mirage we focused on as we have sought to unlock the applications behind this ‘Mantis Catches Cicada’ posture. Which at its core, is nothing short of - ‘engarde with the hook’ (depicted further below).

The reality of this is simple - these hooks with a hand (without the fingers curling), are common holds, ties, binds, and lifts. Think of how you would hook a leg for a knee pick. How you would hook a neck for clinch. An arm for a hold. These hooks are common to many throws, and clinches in Chinese boxing as well as other martial arts the world over. Something I began to realize and wrote about back in 2013. They are not grabbing full speed punches out of the air. This quickly becomes evident when testing our art against a 3-punch-combo from a western boxer.

Mantis boxing form circa 2000.

The move applied.

Someone, at some point, took said hooks, curled the fingers, and stamped the name ‘mantis boxing’ on it. This includes other moves that have ‘faux’ hooks such as - the double hands up engarde with cat stance (mantis catches cicada seen below), curling the hands over into hooks and branding it ‘mantis’. The double rising hands that is also seen in Méihuā Quán (Plum Blossom Boxing), but without the mantis hooks exists as the opener to a mantis boxing classic known as Lan Jie (Intercept and Counter). This is a push counter takedown that is now stylized with unnecessary hooks. Something akin to performance art, rather than real fighting.

Incidentally, that opening move found in Lan Jie, is the exact opening move of the Méihuā Quán form. Minus the hooks. The closing 180 degree turn to mantis catches cicada? Also in Méihuā Quán minus the hooks. Thanks to the works of Zhang Guodong, Thomas Green Carlos Gutiérrez-García, and Ben Judkins, whose works I cited in my research on Qing dynasty totem styles, Méihuā Quán was being spread through marketplaces in Shandong and other northern provinces and heavily influenced the martial arts of the late 1800’s in China. The abundance of ‘plum blossom’ references in the mantis boxing of the turn of the 19th to 20th century cannot be ignored. An entire line of mantis was born with this moniker, forms were named after it, symbols adopted, and moves in forms were direct simulacra.

Mantis Catches Cicada posture found repeatedly in forms of the style Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳).

Cat stance engarde position found in Méihuā Quán (Plum Blossom Boxing 梅花拳), Chángquán (Long Boxing 長拳), Yīng Zhuǎ Quán (Eagle Claw Boxing 鷹爪拳), and likely more Chinese boxing styles. Often depicted as the closing move of the Méihuā Quán form precipitated by the same 180 degree turn found in mantis forms.

The photos above show exactly the same posture. The former is branded as ‘mantis boxing’ by using the hooks. Countless hours have been spent by myself, and other accomplished boxers/fighters trying to crack open the application of this move. Once you look at the prevalent styles in the Shandong region that influenced mantis boxing, it becomes apparent what this posture truly is - engarde w/ mantis. A way of stating - ‘we are mantis’.

When I use the work fake, it is not to insult, or demean any of us who have dedicated our lives to this art. Mantis practitioners are some of the most committed people I have met. The purpose, is to shine full light on the shadows. Exposing our weaknesses and laying bare a truth that we as mantis boxers all need to come to grips with. Our art stopped working a long time ago. We need to be focused on fixing it.

Embracing this truth so that we may turn our attention away from forms, styles, lineage, ceremony, and other superfluous distractions to what really matters - survival. We must turn to the task at hand. Restoring this dying martial art to relevance in the modern world. Making mantis boxing ‘real’ again. Setting it up to be the art it can truly be - a well rounded hand-to-hand combat system that works superbly in the clinch.

To Dissect a Mantis - A Summarized Re-Written History of Mantis Boxing

The following takes all of the data laid out from my timeline research (people, places, events, catastrophes, wars, rebellions, etc), as well as the mantis family tree, and assembles it into a condensed re-write of a more grounded history for mantis boxing. This is a brief overview notating some discoveries and answering questions, as there were many. For the purposes here, I removed mythical backstories and unsubstantiated people. Beginning instead with verified living representatives/associates.

The following takes all of the data collected this past winter from my timeline research (people, places, events, catastrophes, wars, rebellions, etc), as well as the mantis family tree, and assembles it into a condensed re-write of a more grounded history for mantis boxing. This is a brief overview notating some discoveries and answering questions…there were many. For the purposes here I removed mythical backstories and unsubstantiated people. Beginning instead with verified living representatives/associates.

Chinese soldiers 1899 1901 - Leipzig Illustrierte Zeitung 1900 [Public domain]

Here are a few of the questions I hoped to answer in my research on Praying Mantis Boxing.

The records are foggy prior to the 1800’s on the history of Mantis Boxing. Did mantis exist prior to this period?

If so, why did the 4th generation, fresh out of catastrophe on an epic scale in the late 1800’s, and the Boxer Uprisings that followed, suddenly start branding vanilla Mantis Boxing with other names such as - Plum Blossom, Supreme Ultimate, Seven Star? Other Chinese boxing arts of the region/time period did not see this same anomaly yet it was prevalent in Yantai. Did this ‘branding’ happen with the 5th generation of boxers in the first half of the 20th century?

Why are the forms inconsistent with each line of Mantis? If the forms existed as part of Liang Xuexiang’s art, why then did the next generation of boxers change them? If so, then why for the next century, were practitioners so meticulous about keeping these forms intact with little to no disruption?

Why was Li San Jian credited as a Praying Mantis Boxer when there is no evidence that he ever practiced the ‘style’?

Why did Li’s descendant, Wang Rong Sheng, who, by using dates and events, could not have learned Mantis from Li San Jian, but instead clearly learned mantis boxing from his friends - Jiang, Song, Hao, (‘students’ of Liang Xuexiang), end up as a major representative of the mantis style? Especially when he did not have the pedigree the other’s shared?

There is a recognizable crossover with meihuaquan in tanglangquan. What is the significance of the plum blossom symbolism and the prevalence with its use? Is there a link to meihuaquan? This style was spreading through marketplaces in the northern provinces leading up to the Boxer Uprisings, were the mantis boxers in Yantai connected with the uprisings? This creates more questions as the meihuaquan society was adamantly opposed to the violence and attacks on soldiers, missionaries, civilians, and property, such as churches and railways.

According to records, Jiang created and named a form in honor of the boxers connected with the rebellion - ‘Righteous and Harmonious Fist’. Was Jiang connected to the Boxer Uprising? Or was he simply angry at western encroachment and abuses like many in Shandong during this time?

Why is 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing so different from the other lines?

Begin…

A man by the name of Li Bingxiao (李秉霄, 1713-1813), becomes known for his fighting skills in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. He supposedly uses technique(s) that hook with two hands. As he gets older, he’s nicknamed - ‘2 hooks, Li’, or ‘2nd Elder of the Hook’. There is scant evidence of his backstory, but what has been carried down the lineage tree, is suspiciously close to the Confucius origin story. Confucius being highly revered in China for centuries, and originating in the same province - Shandong. Borrowing origin stories is a common phenomenon. Li allegedly teaches a student named Zhao Zhu.

Note: 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing Segway

At this point there is an oral note in the lineage charts that Wei San (De Lin), the accredited founder of the 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing line, met and sparred with Li Bingxiao.

“They could not best one another, but Wei San took some of Li Bingxiao’s methods.”

Thus begins the historical record of 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing. Wei San’s background was in liuhequan (6 Harmony Boxing), aka xingyiquan. The oldest form in this line of mantis is known as ‘duan chui’ - referred to in English as ‘short strikes’, but more appropriately it means - ‘to hammer a weak point, or to beat a weak point or fault with one’s fists’. This form is known to be the creation of Wei San’s student Lin Shichun, who was a bodyguard for the Ding family for a large portion of his career.

Note: This form is quite possibly the oldest representation of xingyiquan in a form.]

This form, known as ‘short strikes’, is the only form in this line at the time and has zero mantis hooks within. Something the practitioners of this line seem well aware of as it varies significantly from their other forms. However, it does share much of its striking and power generation with xingyiquan. I will continue this further down as we get to the branching out of mantis.

Resume…

Zhao Zhu (1764-1847), becomes a teacher himself. He allegedly teaches his sons, and a student named Liang Xuexiang (1810-1895) as Liang grows up. Liang goes on to serve in the military, and becomes a famous biaoshi (security-escort master) & boxer; one with a reputation and record that makes him a well known fighter in his province. His nickname is ‘iron fist’.

Li Bingxiao’s, and then Zhao’s techniques are passed on from Liang Xuexiang’s hands, including his own influences, to a new generation (4th) of boxers that includes his son. With the exception of his son, the teaching of many of his students takes place while Liang is in his late 60’s during a major famine preceded by 3 years of drought. Deathtoll - 9.5 to 13 million people died in the region during this 3 to 6 year time period.

At the time of joining Liang, all of these men were reported to be accomplished proficient fighters before meeting their ‘teacher’. Given Liang’s age and the surrounding events, this student/teacher relation appears to be more indicative of a mentor/client relationship. Liang possibly showing them some of his techniques, but their presence being more in line with protecting him and his family in his old age during extremely violent times.

His counterpart, Li Sanjian, did the same with his two students when visiting a friend in Yantai during this same period of unrest in Shandong province. It would make sense that an elderly, seasoned biaoshi (escort master) entering a foreign city in a time of catastrophe, would also be seeking out young, competent fighters to bring into his stable. Li’s students? Wang Rongsheng, and Hao Shunchang,

Note: Li Sanjian was credited with starting the line known as Seven Star Praying Mantis Boxing. Most people are now in agreement that this is false, and a way for Wang Rong Sheng to pay respect to his teacher, a branding advantage, or otherwise. Li never did mantis boxing, and while it is possible he knew, or knew of Liang, there is no indication he learned mantis from Liang, and was a more famous fighter by all accounts than Liang.

Liang Xuexiang, and Li Sanjian were both renowned escort-masters that ran dart bureaus ( biaoju ) in their lifetime. While they were likely still quite capable at defending themselves, it seems more plausible that they saw the writing on the wall in violent and chaotic times, and circled the wagons so to speak. Calling on younger, more capable fighters to assist them.

These fighters would benefit immensely from this relationship as well. It would after all, be an honor to claim either of these famous veterans as one’s teacher. The younger generation benefiting from this arrangement as much as the old.

The fighters under Liang Xuexiang, if they learned techniques from him, would then add Liang’s techniques (these hooking methods) to their own fighting skills. Each of these men could reasonably be considered rough and tumble fighters since they have each gone through multiple ‘mass droughts/famines’, rebellions, and grew up in a region full of strife. Their home province of Shandong has a reputation in China for producing tough, hardy people, especially boxers. It is a significant region in the history of the nation, where rebellions, bandits, invasions, and catastrophe have all left their mark.

The 4th Generation prior to ‘Mantis’

Style Notes:

Luohanquan, or Arhat Boxing, is a term developed in the early nineteen hundreds by boxers of the time attempting to revise history and accredit their martial arts to Bhudda. Stripping this away, it points to a general ‘Chinese boxing’ style of the Qing era that comprised of many common techniques that were not particular to any one ‘style’. Without the ability to label them, anything not clearly defined, usually gets called luohanquan.

Changquan, or Long fist is a more modern term used to classify the large body of ‘styles’, or more appropriately, boxing methods of the northern Chinese provinces. This can include lesser known styles as well as techniques shared in Hong Quan, Meihuaquan, Tongbei, Tanglang, Ying Zhua, Taijiquan, etc.

Hou Quan, or Monkey Boxing, is by all accounts one of the older ‘systems’ in the north. As evidenced by mention of it in Qi Jiguang’s book, in which he takes survey of the local martial arts in 1560 during the Ming dynasty. 300 years prior to the lives of these boxers.

Ditang, or Ground Boxing, is still alive in Shandong to this day. Evidence is lacking from General Qi’s book on the existence of ditang during the Ming, but it is apparent that it predates, or at the least runs concurrent with mantis boxing.

Liuhequan (6 Harmony Boxing), aka xingyiquan is a style born from the Muslim population in northern China and eventually adopted by the Dai family as the fighting methods for their biaoju company, and the guards under their employ. This is relevant to mantis boxing as it is the primary influence behind the 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing line.

The following styles are accredited to each of these mantis boxers prior to their association with tanglangquan.

Jiang Hualong - luohanquan, hou quan (monkey boxing)

Song Zide - luohanquan, hou quan (monkey boxing)

Hao Lianru - luohanquan

Sun Yuanchang - ?

Wang Rongsheng - changquan (long fist) + ditang quan (Ground Boxing) + whatever Li Sanjian taught him. Although that relationship was similar to Liang and his disciples.

Ding Zicheng - luohanquan (family art), xingyiquan/liuhe.

Four of the above mentioned fighters all opened schools post Boxer Rebellion. One of these boxers, Wang Rongsheng, goes on to teach two people privately. A disciple named Fan Xudong (silk merchant), and Wang’s own son. Prior to this, or during, Wang became good friends with Liang’s disciples, and at this time they shared knowledge with one another. Eventually all adopting the common banner of ‘Praying Mantis Boxing’. Each of them have all survived harrowing times up until this point.

6 Harmony Praying Mantis continued…

It is not until the 3rd generation of the 6 Harmony line (and 5th with the main mantis line), that ‘mantis hooks’ show up in 6 Harmony. Also accompanied by more forms. Ding Zicheng grew up under the tutelage of Lin Shichun. Learning Ding’s methods/bodyguard techniques. As we travel into the 20th century, Ding becomes good friends with one of Jiang Hualong’s students - Cao Zuohou, a 5th generation mantis boxing practitioner, now branded as plum blossom style mantis.

Ding and Cao, go on to share students with one another and cross pollinate. It is noted in their records that their followers could come and go to either school. This period is where we begin to see the additional 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing forms. Post Boxer Uprisings and well into the ‘martial arts for physical education’ stage of Chinese history.

Resume Main Line…

Each one of Liang Xuexiang’s students, as well as Wang Rong Sheng, goes on to brand their own version of mantis (seven star, plum blossom, and supreme ultimate). This draws into question the legitimacy of the existence of a ‘praying mantis boxing’ prior to this generation.

Evidenced by the simple fact that the only commonality among all of their arts are the following:

Forms with shared names.

The move known as ‘mantis catches cicada’ (engarde with hooks). Which appears to be nothing more complex than ‘branding/marketing’.

And the hooking techniques - seize leg, twisting hook, piercing hooks, lifting hook.

Nothing listed above is unique per se. The hooking techniques, absent the extra, and highly impractical curled fingers, all exist in Shuai Jiao records. Perhaps these methods were unique to this area at the time, exclusive in the setups to initiate the moves, or the follow-ups to the technique if the move is countered. The last being of particular interest to other fighters as is found in modern fighting arts.

The forms vary from each line at this point, or perhaps were mutated in the generation(s) to follow.

Note: Assuming the style existed prior to these boxers, or more specifically the forms of mantis boxing, and the methods of the mantis were Liang Xuexiang’s and his teachers before him; why would these boxers take it upon themselves to change these forms? Practitioners since then, have been incredibly adept at keeping these forms intact for the past 100+ years. Why would all of these boxers alter them?

Without supporting evidence to the contrary, it is difficult to accept that the name Praying Mantis Boxing existed prior to this point in history. It appears more likely that it was created by these 4th generation boxers/friends in the early 1900’s post Boxer Uprising, well after Liang Xuexiang, and Li Sanjian are deceased.

Did these younger boxers/friends brand their stuff ‘mantis boxing’ as a group? Was it based on the techniques from Li Bingxiao they now have in common with one another?

This would explain how:

They each have different names of their mantis style. Each able to keep an individual identity because they all had their own techniques unique to themselves prior to incorporating these ‘mantis’ techniques of Li Bingxiao on down. We end up with labels to signify the differences of each boxer prior to intercepting mantis - seven star, supreme ultimate, plum blossom.

It perhaps explains why the forms are inconsistent in each line. Shared in name only, but beyond that never having more than 2 lineages with consistent forms to one another. If the forms were handed down for generations prior, they would be sacred and undisturbed, not changed by Jiang, Hao, and Wang.

Liuhe tanglangquan (6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing) is a good example of this. The second generation of 6 harmony style (Lin Shichun) created a form known as Duan Chui (the only form prior to the 4th generation. Duan Chui still exists to this day, relatively undisturbed. Practitioners of all other lines of mantis since this period, have been obsessively adept at keeping these forms well intact with minimal changes. This makes it all the more improbable that the 4th generation would all of a sudden change the forms as they saw fit. Unless…there were no forms prior to this time…or forms were considered insignificant and not revered as they often are today.This would explain how, and why, Li Sanjian receives an honorary accreditation for a style he never did. It wasn’t a ‘style’ at all. It was a handful of techniques that Wang Rongshengs’ friends showed him. Wang never studied with Liang Xuexiang, as evidenced by the fact that he took the mantis moniker yet still claimed Li Sanjian (a non-mantis boxer) as his teacher.

If Wang had studied with Liang, and then changed his forms without giving proper credit, it would be incredibly disrespectful, and dishonorable. His ‘friends’ would certainly take issue with this. Instead, if it were simply a handful of methods from Liang that were passed down, it would make it easy to blend in with the other things Wang already knew and learned. Wang keeps his ‘teacher’ because there is no pure ‘line’ of mantis boxing to be loyal to prior to this.This also identifies why one of Wang Rong Sheng’s descendents was selected to represent ‘mantis’ in Jin Wu. Wang wasn’t ‘true mantis’ under the ‘Li Bingxiao -> Zhao Zhu -> Liang Xuexiang line’. So why would one of his students be picked to represent the mantis style for such a major endeavor in the south such a Jing Wu? If it really mattered that is? Why not one of the ‘true heirs’ - Jiang, Song, Sun, or Hao’s students? These boxers even had schools at the time, and Wang was only teaching one non-family member.

Lastly, this would explain why it was so easy for a 3rd generation descendant of Liuhe/xingyiquan to blend ‘mantis techniques’ that he learned from a 5th gen mantis practitioner, with his style of liuhequan. Combining a few techniques using the foundation taught to him by Lin Shichun, Ding Zhicheng wasn’t learning an extensive ‘system’, merely some techniques unique to these mantis boxers at the time. But certainly not unique in all of China, or the world.

What about the forms?

The forms could not have mattered. They obviously were not cemented in place. They were certainly not sacred if they were so freely altered. The techniques within these ‘sacred sets’ were common to other ‘styles’ of Chinese boxing, and Shuai Jiao in the region during that period of the Qing dynasty.

The curled finger mantis hooks expressed within the forms, are not necessary for the techniques to work. They all too often confuse observers/practitioners on the true martial intent of the move. If anything, they prevent the actual moves from working properly due to aesthetic stylization being placed above practicality.

What about the keywords? Aren’t they unique? Do they not define it as ‘mantis’?

No. I no longer believe this to be the case. These words are also part of the common boxing vernacular of the time. They offered nothing unique that isn’t found in Cotton Boxing and other fighter’s systems. Evidence by a few of the 12 keywords, and a plethora of techniques being shared with taijiquan. The mantis keywords that are not primary taijiquan principles, are listed in other subtexts as supplemental to the primary 13 keywords of taijiquan. A comparison can be found here in this working document Praying Mantis Boxing vs. Supreme Ultimate Boxing.

In Summation

As we would find in Brazilian jiu-jitsu today, with someone using the infamous ‘spider guard’ synonymous to that style - in mantis we have Li Bingxiao using his ‘double hooks’, aka - mantis controls/takedowns that caused him to stand out from the crowd of other boxers. Giving him an edge.

His methods were only allowed to exist as a ‘style’, because of a unique set of circumstances in history. Occurring at the end of an era of combat for survival, and the beginning of an era of wuxia, and physical education for profit.

Having seen and studied a wide range of Chinese boxing forms, provides me with a unique vantage point to be able to compare forms from various Chinese boxing systems north and south. The following are the moves I have found to be unique to ‘mantis forms’ that I have not seen in the other styles (this does not mean they do not exist. My knowledge/experience is certainly no where near all encompassing):

Seize leg (one variation)

Wicked knee

Hanging Hooks

Twisting Hooks

Pierce hooks (Edit: I later realized this is a shared application with one of the moves in Yang taijiquan’s - snake creeps down)

Possibly the ‘kicking legs’ methods are also unique.

All of the above methods are easily shared with competent experienced fighters/martial artists. Simple, easy to grasp methods. Akin to what fighters would be learning from one another, rather than convoluted systems of 70, 80, or 100’s of techniques/moves.

If we take each ‘boxing set’ at face value as a fighter’s ‘system’, consider for a moment how unlikely it would be to collect those in times of chaotic strife...

----

Arriving full circle -

We need not be bogged down by the chains of the past - politics, lineage, forms, etc. Take the best, discard the rest.

What is Mantis Boxing? An arsenal of hands, elbows; knees, kicks; throws and locks from Chinese boxing. We have the keywords to define it, and learn by. We have the roots. We honor them in our practice and continuation of the art.

What Can BJJ Teach Us About Qing Dynasty Martial Arts? - Randy Brown - MAS Conference 2019

This podcast is a re-recording of a talk I gave at the 5th Annual Martial Arts Studies Conference held at Chapman University in Los Angeles, California in May 2019. The event was hosted by Dr. Paul Bowman, and Dr. Andrea Molle. A two day extravaganza of martial arts history, politics, and culture. There is amazing research into the martial arts taking place around the globe today. It was an honor to be a part of this significant event, and contribute in some small way to the Martial Arts Research Network. Below is a copy of the…

This podcast is a re-recording of a talk I gave at the 5th Annual Martial Arts Studies Conference held at Chapman University in Los Angeles, California in May 2019. The event was hosted by Dr. Paul Bowman, and Dr. Andrea Molle. A two day extravaganza of martial arts history, politics, and culture. There is amazing research into the martial arts taking place around the globe today. It was an honor to be a part of this significant event, and contribute in some small way to the Martial Arts Research Network. Below is a copy of the abstract submission for my talk at the conference to help lay context before listening.

Abstract

What Can Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Teach Us About Qīng Dynasty Martial Arts?

The continually evolving art of Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) and the journey of this style throughout the 20th century can provide insights into key elements of the Qīng dynasty Chinese martial arts, helping to demonstrate similar developments in the ‘Chinese Boxing’ systems of that era. Specifically, by following the modern evolution of BJJ, it is possible to gain insights into the sudden appearance of totem styles or subsets across China, how these anomalies become styles in their own right, and how they survived and thrived for over a century. A martial arts cross-cultural comparison of style subsets within BJJ, which have developed since the early 1990s, can be juxtaposed with the pre-modern development of comparable ‘subsets’ within Qīng dynasty ‘Chinese boxing’. On the other hand, the survival and globalization of this stylization in China differs with how developments within BJJ propagate, where instead changes become rolled into a pool of common knowledge and do not take hold as independent systems or alternative styles outside of the core art. A question needs to be asked, did ‘Chinese boxing’ of the era, have a similar common pool of knowledge? Qī Jì guāng’s manual would hint at such. Within ‘Chinese Boxing’, attributes, feats, or skills defining one fighter over another became definitive styles of their own right due to events of the time, compared to a failure in modern times for these subsets to survive independent of BJJ, even though properly vetted in the crucible of worldwide tournaments. In the Qīng dynasty a confluence of events which included rebellions, opium wars, global humiliation and the collapse of a dynasty, began to solidify these subsets as styles in China. Eventually, cultural industrialization of Chinese martial arts, notably through the Hong Kong movies, ingrained these styles into popular culture with the result being securing their legitimacy to the public eye without any evidence of martial prowess.

Keywords:

Chinese martial arts, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, Qīng dynasty, animal styles, Chinese boxing

Biography

Randy Brown

Randy is an owner and teacher at Randy Brown Mantis Boxing, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu in Acton Massachusetts. Randy has over 20 years’ experience with praying mantis boxing with additional cross-disciplinary training in various Chinese martial arts: eagle claw, Hung gar, long fist, Yang, xingyiquan. Randy has trained in 17 Chinese martial arts weapons and specializes in staff, saber, sword, and military saber and has seven years’ experience in Brazilian jiu-jitsu. He has published a number of articles in martial arts journals, including Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine and Journal of 7 Star Mantis and has competed and placed in both the U.S. National Wu Shu Championships and the International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation. Randy holds a Bachelor of Science in computer science from Franklin Pierce University. In his spare time, he enjoys writing, drawing, painting, and hang-gliding.

Bibliography

Wile, Douglas. Lost Tʻai-Chi Classics from the Late Chʻing Dynasty. State University of New York Press, 1996.

Lorge, Peter. Chinese Martial Arts from Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Silbey, David J. The Boxer Rebellion and the Great Game in China. Hill and Wang. 2012.

Tong, Zhongyi. Cartmell, Tim (translator). The Method of Chinese Wrestling. North Atlantic Books, 2005 (original 1935).

Kennedy, Brian. Guo, Elizabeth. Jingwu The School that Transformed Kung Fu. Blue Snake Books, 2010.

Leung, Shum. The Secrets of Eagle Claw Kung Fu Ying Jow Pai. Tuttle Martial Arts, 1980, 2001.

Keown-Boyd, Henry. The Fists of Righteous Harmony - A History of the Boxer Uprising in China in the year 1900. Leo Cooper, 1991.

Kennedy, B., & Guo, E. Chinese martial arts training manuals: A historical survey. Berkeley, CA: Blue Snake, 2008.

Laurent Chircop-Reyes. Merchants, Brigands and Escorts: an Anthropological Approach of the Biaoju ffff Phenomenon in Northern China. Ming Qing Studies, WriteUp Site, 2018, Ming Qing Studies, 2018, http://www.writeupsite.com/eng/ming-qing-studies-2018.htmlff. ffhal-0198740

Article on Biaoju Companies - https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%90%8C%E5%85%B4%E5%85%AC%E9%95%96%E5%B1%80/8761785

E. Henning, Stanley. (1999). Academia Encounters the Chinese Martial Arts. China Review International. 6. 319-332. 10.1353/cri.1999.0020.

Interview with the last Manchu archer - By Peter Dekker, January 23, 2015 - http://www.manchuarchery.org/interview-last-manchu-archer

Library of Congress maps - https://www.loc.gov/maps/?c=150&fa=subject:maps%7Clocation:china%7Clanguage:chinese&st=list

List of Rulers of China - Metropolitan Museum of Art - https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chem/hd_chem.htm

Li San Jian - http://www.shm.com.cn/special/2015-07/22/content_4365668_2.htm

McCord, Edward A. The Power of the Gun. University of California Press, UC Press E-Books Collection, 1982-2004 - https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft167nb0p4&chunk.id=d0e288&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e288&brand=ucpress

Guodong, Zhang & Green, Thomas & Gutiérrez-García, Carlos. (2016). Rural Community, Group Identity and Martial Arts: Social Foundation of Meihuaquan. Ido Movement for Culture. 16. 18-29. 10.14589/ido.16.1.3.

The Mantis Cave - Fernando Blanco - http://www.geocities.ws/mantiscave/fernando.htm

The Taiping Institute - http://www.taipinginstitute.com/courses/northern-central-plains/tanglangquan

Judkins, Ben. Lives of Chinese Martial Artists (13): Zhao San-duo—19th Century Plum Flower Master and Reluctant Rebel - https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2017/04/20/lives-of-chinese-martial-artists-13-zhao-san-duo-19th-century-plum-flower-master-and-reluctant-rebel-2/

Judkins, Ben. Research Notes: Xiang Kairan on China’s Republic Era Martial Arts Marketplace - https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2016/08/14/research-notes-xiang-kairan-on-chinas-republic-era-martial-arts-marketplace/comment-page-1/#comment-81216

Perdue, Peter C., Sebring, Ellen. The Boxer Uprising 1 - The Gathering Storm in North China (1860 - 1900) - https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/boxer_uprising/pdf/bx_essay.pdf

The Worst Natural Disasters by Death Toll - Contributed by Administrator - June 15, 2007 Last Updated April 06, 2008 - http://www.armageddononline.org

Professor Peter Lorge's keynote, 'The invention of "traditional" martial arts" - given at the July 2017 Martial Arts Studies Conference, Cardiff University - https://youtu.be/9Y_1tKVvwNc

Mantis Boxing Historical Timeline - Qing Dynasty to Republican Era

A true Mantis Boxing Historical Timeline from the Qing dynasty to the Republican Era. This tool was pivotal in drawing conclusions in my research on the history of Praying Mantis Boxing. Months of investigation culminated and presented in this beautiful chart designed by Bruce Sanders. Now available for your own research or enjoyment.

How to Escape the Clinch

We were in Los Angeles last week for the 5th annual Martial Arts Studies Conference, and after it wrapped up, we dropped in on Sensei Ando at his location. While there, I showed some 'clinch escapes' that I like. Ando asked me to come home and share the follow-up to the escapes - takedowns!!!

We were in Los Angeles last week for the 5th annual Martial Arts Studies Conference, and after it wrapped up, we dropped in on Sensei Ando at his location. While there, I showed some 'clinch escapes' that I like. Ando asked me to come home and share the follow-up to the escapes - takedowns!!! We tried to get him to come out here and finish the shoot, but he said the pie in New England is inferior.

Part 1 - Neck Slice/Frame Escape - Slant Chop a.k.a. - Single Whip (擔扁), Single Whip to Embrace Tiger, & the Piercing Hook, also known as Snake Creeps Down in Tai Chi.

A Dark Start: My Disasterous Beginning Into Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

What I am about to share with you, is my early journey into Brazilian jiu-jitsu. My first attempts were not exactly a ringing endorsement of the art. What happened to me? What can you learn from my experience? Why did I keep trying after all of this?

One of the common reasons deterring people from learning this amazing, life changing art, is contact. Like some of you, I have an issue with personal space. The idea of getting on the ground and ‘rolling’ around with someone had never appealed to me primarily for this reason. I even wrote an article about it, to share how I relate to those who are looking at the art, but find the level of contact to be a barrier to entry.

What I am about to share with you not exactly a ringing endorsement of the art of Brazilian jiu-jitsu. It a tale of my ealry journey into BJJ. If nothing else, it provides a cautionary tale, of how important it is to find a good coach/gym to train with.

A majority of my injuries in martial arts in the past 20+ years, and all of the most severe ones, have been from Brazilian jiu-jitsu. And yet, I would still recommend the art to anyone, under the right circumstances.

The Beginning

As I started to find truth in mantis boxing after years of training, the UFC was growing more popular than ever. The reality and efficacy of ground fighting and it’s necessity began to seep into my periphery. I would pontificate questions such as -

‘What would I do if someone took me to the ground in a fight?’

‘Would any of my skills, after years of martial arts training, help me?’

After all, someone that is even just incrementally larger than us, has an inherent advantage due to gravity, and the laws of physics. Couple this with a season or two of wrestling in high school/college, or a football tackler, and we have serious deficiencies in our combat capabilities; no matter how good our stand-up fighting is.

When involved in an altercation, once we’re on the ground, which could be from a slip, trip, or fall of our own accord, or after an opponent grabs us for dear life as we throw them to the ground - taking us with them - the game is quickly over if they land on top of us.

I am not the largest guy on the planet, even when I was 70 lbs heavier than I am now. Having the knowledge and technical ability to deal with an opponent in a ground situation was to me, becoming more and more evident, for obvious reasons.

Brazilian jiu-jitsu provides solutions to the problems we face in ground combat, better than any other martial art. Using timing, technique, and those same aforementioned pesky laws of physics, we can turn the laws to our advantage, overcoming larger, stronger, and heavier opponents, if we ever end up on the ground in a self-defense situation.

So, as we said in the Army - I ‘sucked it up and drove on’. Putting my ‘human contact’ issues aside, I undertook a search for a BJJ school to train in. And there the problems began…

ROUND 1

One of my early coaches in the martial arts had some training in BJJ. How much, I never found out. We were discussing my interests in learning a bit of ground fighting and he offered a trade. I would share one of the historical mantis boxing sets I learned while studying with another coach, and he would train me in Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

My first lesson included a few rudimentary tips on what not to do on the ground while in the mount position. This was followed up by my first introduction to a rear naked choke.

I stood there in a compliant stance excitedly awaiting my lesson in one of the most powerful tools in BJJ - aka The Lion Killer. Suddenly, I felt a sharp pain in my throat as the man I just entrusted with my life, put the choke on fast and hard; crushing my larynx. It took 6 weeks for my esophagus to pop back out. Thus ended my my first (and last) lesson with him.

ROUND 2

For my next attempt, I contacted an instructor a few towns away. We discussed my background, and I made it clear I knew nothing about ground fighting. I was starting over in this art and I would like to put on a white belt and be treated like any other beginner. Starting from the ground up (no pun intended).

The first class went relatively well. I had a few minor issues, but nothing to stop me from going back for another class. I was committed to doing this after all. Itching to learn.

I returned two days later for my second class. I left with a ripped ear, tweaked elbow, broken toe, and my knee out of whack. The instructor somehow deemed it acceptable in my first week, to throw me into a 40 minute ‘rolling’ (sparring) session with people who had been training for years. Seems as though there was a plan to try and wipe the floor with me.

Finding myself incapable of just giving up, I fought back…hard. It cost me, but ultimately it cost that instructor too - I never went back.

This turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Said coach went to jail years later for assaulting a 14 year old female student.

ROUND 3

Trying to be smarter, my next experience was born by referral. I came across an MMA/BJJ coach teaching at an associates of mines school, halfway across the country. I was visiting for a weekend of seminars. In between I rolled with this skilled grappler for a couple hours. He shut down everything I had. He obviously knew his craft.

He was also approachable and seemed vested in teaching me how to succeed. I enjoyed it and wanted to learn more. Additionally, he was also ex-military like myself, so we understood one another on a training and practicality level.

At first it was a good fit. I flew him across the country to do a weekend of seminars at my gym, and get some one on one training in on the side. All went well with the seminars, and we had some good rolling/training afterwards. Until his PTSD kicked in.

He tore my shoulder out. Not once. Not twice. Three times in one hour. With two extreme americana shoulder locks, and a kimura shoulder lock. I barely escaped this encounter without a total shoulder replacement surgery.

This day cost me thousands of dollars in medical repairs/treatments, A year plus of treatment entailing hundreds of hours of physical therapy and recovery. Needless to say, I left him behind, and continued searching. I’m sure, if you are still reading this, you are wondering why the hell I would continue on? Good question.

Stubborn. To a fault.

ROUND 4

The Gracie family, considered by some to be the founders of the art in it’s more modern form, had a school in Los Angeles. They were running an instructor certification and training program that sounded enticing. I watched some interviews with them and they appeared upstanding individuals with an earnest and sincere approach to teaching BJJ, without breaking everyone that came through the door.

1st class with Dedeco - 8/2011

I began looking seriously at their Instructor Training Program. The downside was it was going to cost thousands of dollars, and a great deal of travel.

Additionally, thousands upon thousands of dollars (about $14,000 dollars by my calculations) to get this program underway in my academy - due to affiliation fees, rules, branding, and contractual agreements I will not bore you with here.

Instead, I pulled one of my instructors aside in the school. She was also interested in learning ground self-defense. I purchased some instructional videos and Holly and I started training BJJ basics a few times per week. This continued moving the ball forward, slowly.

With all the challenges I faced in the world of Chinese boxing, I was no stranger to having to teach myself. I was beginning to think this was once again going to be a reality I would have to accept.

ROUND 5

My contacts across the country came through once more (this time positively), and hooked me up with someone who would go on to become my final BJJ instructor/coach.

Andre ‘Dedeco’ Almeida was located south of Boston in Rockland, Massachusetts. A little less than 2 hours drive from me. He came highly recommended, and at the time, his Best Way Jiu-Jitsu was being used to train top UFC fighters.

For obvious reasons, I was a bit more gun shy about diving into another bad experience. So I asked to meet him for coffee first so we could discuss his approach to training. We met at his favorite coffee shop (Starbucks), and broke the ice, or beans.

IBJJF Summer Open ‘12

Dedeco, as he prefers to be called, was super nice. He seemed like an upstanding person. After listening to my experiences with BJJ thus far, he was appalled. It insulted him that his livelihood and passion was being misrepresented. This was not way beginners were to be introduced to the art he had been studying since he was a child in Brazil.

Something he said stuck with me after that first conversation -

“Randy, I am not going to have you ‘roll’ (what we call sparring in BJJ), until I teach you how to roll.”

Well didn’t that make a boat load of sense!!! A principle I followed in my own teachings when starting someone out with striking and kicking in mantis boxing. I wondered what short straw in life I drew to go through all this nonsense in order to find a decent coach?

I started private training with Dedeco shortly thereafter (Aug 2011), He introduced me to what I would come to appreciate as the amazing art of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, and the myriad benefits it has to offer.

BJJ Ranks

BLUE ENOUGH

My plan when I started, was to simply get to a blue belt level. This was, at the time, a significant bench mark for this martial art (it still is depending on the school/coach). Fighters would brazenly step into the cage in UFC fights donning a blue belt, like a proud peacock. Unlike other styles of martial arts, that give out black belts like candy, the first belt you get in BJJ (a blue belt), is a monumental achievement in and of itself.

As I trained more and more with Dedeco, and began meeting his other students, and his friends who owned BJJ schools, and their students, I began to witness an amazing family of people that were pushing one another to get better and better, but without injuring one another all of the time.

Left to right - Dedeco, myself, Ricardo Liborio

And juxtaposed vs the Traditional Martial Arts World’ I was accustomed too, instead of the stuffy, overly dogmatic experiences I witnessed in other styles of martial arts, what I experienced instead was a relaxed and friendly environment that fostered creativity, freedom of expression, and ingenuity. Embracing the personal expression of an individual’s artform, that we devote years of our lives to.

I later met Dedeco’s teachers (Ricardo Liborio, and Ricardo De La Riva), and witnessed firsthand, the sincerity and kindness in these men. REAL men, who were extremely accomplished fighters, and champions, yet expressed no ego, bravado, or malice. Just humility, and genuine care for the growth of others, and their art.

This was such a powerful experience. It changed my life, and my entire school/approach to martial arts. I mirrored these training approaches in my own mantis boxing program, and my team overall. It had a profound affect, improving my own skills, my team, and above all else, my abilities as a teacher to help others with their art.

The skills inside Brazilain jiu-jitsu are some of the most powerful tools you can ever have in your arsenal. If you train the art with due diligence, it will reward you in spades. After training for a time, if someone is dumb enough to take you to the ground with ill intent - that attacker just stepped into the deep blue waters of the darkest ocean, and you are the shark!

That...is why this style is now part and parcel with my mantis boxing inside the halls of my academy, and within my heart.

If you are inspired to learn and embody all that BJJ has to offer, my advice is to take your time and find a coach, and team that are right for you. Do not settle! It is your money, and more importantly your time, and even MORE importantly - your body.

Randy Brown

BJJ Black Belt

Mantis Clinch Counters with Sensei Ando @ Happy Life Martial Arts

In this video Ando suffers through some neck puncturing on my behalf (and a possible stab wound) so we can cover some of the clinch escapes that don’t work all the time, along with some more reliable ones that I prefer. Thanks for watching!

We had the honor of visiting with Ando from Happy Life Martial Arts in Los Angeles this past weekend. Aside from the great hospitality and amazing company, we had some time for a quick tour of his stomping grounds, as well as shooting a video or two.

In this video Ando suffers through some neck puncturing on my behalf (and a possible stab wound) so we can cover some of the clinch escapes that don’t work all the time, along with some more reliable ones that I prefer. Thanks for watching!

Subscribe to Happy Life Martial Arts for some great tips - https://www.youtube.com/user/AndoMierzwa or visit Ando’s website for tons of content - http://www.senseiando.com/

Coach Holly hanging with Sensei Ando @ Happy Life Martial Arts

We had the honor of visiting with Ando from Happy Life Martial Arts in Los Angeles this past weekend. Aside from the great hospitality and amazing company, we had some time for a quick tour of his stomping grounds, as well as shooting a video or two. Here is Coach Holly showing some of her tips for the scissor clip with Sensei Ando!

We had the honor of visiting with Ando from Happy Life Martial Arts in Los Angeles this past weekend. Aside from the great hospitality and amazing company, we had some time for a quick tour of his stomping grounds, as well as shooting a video or two. Here is Coach Holly showing some of her tips for the scissor clip with Sensei Ando!

Subscribe to Happy Life Martial Arts for some great tips - https://www.youtube.com/user/AndoMierzwa or visit Ando’s website for tons of content - http://www.senseiando.com/

The Rowing Hook 2 - 7 Star

Here's a second variation of the rowing hook maneuver found in mantis boxing forms. This time…

Here's a second variation of the rowing hook maneuver found in mantis boxing forms. This time Mantis boxer Vincent Tseng is going to show his discovery. This variation is used when the opponents leg is in front of us versus behind.

Size Matters!!! - Part 2 - Spider Guard

Part 2 of our new series on how size affects your martial arts. This is another one for BJJ - Spider Guard. There are some important…

Part 2 of our new series on how size affects your martial arts. This is another one for BJJ - Spider Guard. There are some important differences with leg/foot position that can matter if we are a smaller, or larger grappler. Thomas and Vincent assist me in demonstrating a good foot position for spider guard depending on your height.

The Rowing Hook - A Flank Takedown

This is a unique throw that shows up in some Chinese boxing styles such as Mantis Boxing and Shuai Jiao. In mantis boxing it appears in forms as a single leg stance and what seems to be an…

This is a unique throw that shows up in some Chinese boxing styles such as Mantis Boxing and Shuai Jiao. In mantis boxing it appears in forms as a single leg stance and what seems to be an uppercut. Without context, it's hard to see what the move does. It's highly effective for a unique circumstance we can find ourselves when battling in the flank position. Today Vincent is going to help demonstrate the position you find yourself in where this counter shines.

Size Matters!!! - Part 1 - Turtle Position

New series we're releasing on size matters. When doing martial arts of any kind, size is a determining factor in what moves will work, and what…

New series we're releasing on size matters. When doing martial arts of any kind, size is a determining factor in what moves will work, and what won't for you and your size. We're going to highlight some common positions where this stands out.

In the first episode we tackle the turtle position in BJJ/MMA, and how to choose the right escape for you and your opponent.

Countering the Clinch (Lǒu 摟) - FRAME! FRAME!! FRAME!!!

The clinch can be a nasty place to be stuck. When our opponent is larger, and/or stronger, and has their hooks on our neck, some of our escapes can be difficult to…

The clinch can be a nasty place to be stuck. When our opponent is larger, and/or stronger, and has their hooks on our neck, some of our escapes can be difficult to pull off. Building frames can help shut down the clinch, but we have to know where to go next after building the frame. Knee strikes, arm triangles, hip tosses. Check it out.

Tear Down the Monkey - Fight Stance Revamp

A critical analysis of the fighting stance we've been using for years. And why I got rid of it.

I recently went through some changes in my teaching and practice. One of these recent changes was in our fighting stance. The reasons for these are many, and too lengthy to explain for these purposes. However, the root of any changes I make are always born of a desire to improve things for myself and my students.

Let’s compare the stance we were using for years, the Monkey Stance, with the…

A critical analysis of the fighting stance we've been using for years. And why I got rid of it.

I recently went through some changes in my teaching and practice. One of these recent changes was in our fighting stance. The reasons for these are many, and too lengthy to explain for these purposes. However, the root of any changes I make are always born of a desire to improve things for myself and my students.

Let’s compare the stance we were using for years, the Monkey Stance, with the 3 Dimensional Stance, 4-6 Stance, or 40/60 Stance common to other Chinese boxing systems from the same region and era.

Monkey Stance (Hóu Shi 猴势)

Monkey Stance

The ‘monkey stance’ is found in seven star praying mantis boxing, plum blossom praying mantis boxing, and supreme ultimate praying mantis boxing. Although used within these branches of mantis boxing it is not necessarily a ‘sparring’ stance. It shows up within moves in the boxing sets of old, but usually aligns with the execution of specific techniques. More common in these old forms, is actually, the bow stance, or mountain climber stance.

Upon recent discovery, these monkey stance techniques are typically leg wrap takedowns which necessitate this stance in order to shadow box the move absent a partner, without falling on one’s face. I had fully integrated this stance into my fighting and movement patterns after having learned it from a coach I worked with for years. He taught/used this monkey stance in fighting predominantly because of the correlation he found in Western Boxing. However, the latter is usually in a much higher posture due to the lack of necessity in defending kicks and takedowns.

The higher posture found in western boxing allows for increased mobility when using this stance/footwork, and has less detrimental effect on the fighter’s balance. The feet are closer together which leaves the stability of the boxer mostly uncompromised. This has issues in a mixed martial art arena, which is why you do not see MMA fighters using this stance.

When used as a lower stance (as we were doing), the monkey stance is rather unstable and rife with problems. Least of which is it’s mobility. Let’s rip it down so we can understand the inherent strengths and weaknesses of this ‘stance’.

Strengths

Offers solid defense capabilities - decreased profile for target acquisition from the opponent.

Forward position offers quicker range to target - a 50/50 weight displacement puts the range to target of the striker closer to their target. This helps get hands on the opponent faster and offers a range assist for smaller fighters.

Increased mobility - this is only active when the fighter is in a high stance. Otherwise, this is negated.

Protects the Knee - this is one of the finer points of this stance in my opinions. With the knee over the toe, the boxer is almost immune to cross kicks and side kicks which are designed solely to attack the knees. Proper execution of this stance nullifies this threat.

Good in the Clinch - when engaged in grappling, the 50/50 position of the monkey stance, and the lowered center of gravity are where this stance shines the most. A stance with weight distribution forward, or behind this 50/50 center of gravity point, causes us to be open for pulls, pushes, and a variety of throws. This, in my opinion, is where the monkey stance becomes necessary, and relevant.

Weaknesses

Unstable - this stance is extremely unstable. Especially from lateral attacks such as haymakers, which are an extremely common strike even from novices. The stance can become stable with a great deal of tweaking and perfection, but the amount of time required to do this, certainly nullifies its benefits, which are few compared to other stances. The ease of which a smaller fighter can be rocked and toppled makes this a dangerous choice when looking at stances to use in hand-to-hand combat.

Difficult for beginners - there is a massive learning curve with this stance. When sitting in this stance to maximize its effective traits, it is extremely finicky. Knee over toe, back foot angle/position, hip alignment, shoulders over hips, balls of the feet, hips dropped. Remembering all of that, while trying to move in a completely foreign manner that is counter to our human movement patterns, can take a casual practitioner years to get down. With diligent focus, the stance still requires hundreds of hours of training to overcome and perfect the stability and mobility deficiencies.

Decreased mobility - when hunkered down in this stance it is lacking mobility in order to maximize defense. While defense is great, it is not the endgame. The ultimate goal, is to defeat our opponent(s). Imagine being faced with multiple attackers, and sitting in a fighting stance that creates a 50% speed reduction. Or you are in a cage fight, facing a mobile, and speedy opponent. You won’t keep up.

Vulnerable to Leg Kicks - The forward 50/50 position for the center of gravity, causes the leg to become a closer target for our opponent’s leg kicks. Additionally, more weight on the forward leg, causes an extreme delay in response time in getting the leg up to check, or avoid an opponent’s leg attack. This is the number one attack I would use against someone in this stance. Destroy leg. Compromise their mobility, and take their will to fight.

Exposed Striking Power - in order to generate maximum power in this stance, a fighter must learn to shuffle with each strike, or twist/rotate the hips when throwing off the rear hand. This is common in western boxing for producing awesome striking power. However, when we twist and throw ‘long’ punches/strikes we create a longer opening in our defense that is susceptible to counter-strikes. This window of opportunity can be an issue against a seasoned opponent.

Takedown Defense - if you were to classify each type of throw, trip, takedown that exists within martial arts styles the world over, and then categorize them based on frequency of use, the single and double leg takedown would be at, or near the top of that list. These are common weapons in the arsenal of wrestlers the world over. The monkey stance, becomes necessary within the clinch, but when used prior to the clinch phase, it creates a leg position that is extremely vulnerable to single/double leg takedowns. Additionally, the 50/50 weight distribution again creates a speed limit on the ability to sprawl. A veteran shoot fighter that is highly adept at setting these up, will close the gap from striking range to the takedown in the blink of an eye. Any speed/range advantage we can have in striking range can be a deterrent against these attacks. This stance is not the choice selection when it comes to this.

The Three Body Solution - San Ti Shi (三体势)

Used in a derivative of Mantis Boxing known a 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing, and a newer (1900’s) subset of that known as 8 Step Praying Mantis Boxing. The 6 Harmony line has roots in another style of Chinese boxing, that is derived from Liuhe Xingyiquan (6 Harmony Mind Intent Boxing). A system taught by the Dai family in Ming dynasty who owned a security/escort company known as a biaoju. This explains why this line has an entirely different stance than the other branches of mantis boxing.

The concept is - simple striking with solid footwork designed to maximize power. The striking was used in conjunction with blocks/intercepts and could be blended together for combinations as needed. Throws and other techniques were included in the system, but it was overly simplified to keep the training methods efficient and effective. Something you would want when training security and bodyguards.

The stance used in ‘mind intent boxing’ is called a San Ti Shi (three dimension stance 三体势) and while not unique to this one style, it is effective. It appears in other Chinese boxing systems originating from northern China as well.

In my opinion, this is a much better stance for a variety of reasons. Hence why I began adopting it in my system and discarding the monkey stance except when grappling. The following breaks down the advantages and disadvantages of the three dimensional stance before we get into the details on proper execution.

Strengths

Stability - this stance is incredibly stable, especially when compared with the monkey stance. The 40/60 weight distribution, with hips dropped offers a stable platform for striking, kicking, or defending even from lateral angles of attack.

Ease of Use - one of my biggest criticisms of the monkey stance is it’s long and finicky learning curve. For beginners who are training 2 to 3 hours per week, the san ti stance is much easier to learn, and execute. Unlike the monkey stance, it takes very little maintenance to get people on board with the concepts and application of it.

Power Generation - next to stability, and ease of use, this is probably one of the greatest advantages of this stance. The power generation capacity from this stance versus the monkey stance is phenomenal when looking at a fixed stance platform to compare. The monkey stance can generate power as well, but usually at cost of defense, or stability when committing to the twist execution to produce the force. The 3-dimension stance however, can outperform without compromising the integrity of the defense/position of the fighter.

Kick Defense - the round kick is a powerful weapon in a boxers arsenal when used as to attack the lead leg of the opponent. Opposite the monkey stance, the three dimension stance offers a quicker reaction time to move our leg, or shin-check the opponent’s attacking leg. When it comes to groin kicks, the narrow stance of the san ti offers defense by itself. Once again, the lighter weight on the front leg allows for a quick reaction time against leg attacks, knee attacks, or groin attacks.

Takedown Defense - this is specific to shoot takedowns such as single leg, double leg, or rushing/tackle takedowns. The rear sitting san ti stance, offers a larger timespan to initiate a sprawl, or rearward step to avoid these takedowns. The forward weight of the monkey stance was not useless, but the timing was harder to get down.

Range Manipulation - another exceptional advantage to this stance, is the ability to manipulate range. The slight rearward weight distribution offers an appearance to the opponent that we are further away than we really are. The lead foot position indicates our true range to target. We can therefore, get that position across the ‘critical distance’ line of our opponent with them unaware that we moved in. This allows for us to gain range advantage on an offensive assault. Additionally, as mentioned above, the defense is also assisted with the range increase offered by the rear sitting san ti stance compared with forward-weighted stances.

Weaknesses

Knee exposed - if your stance sits too far back, meaning you violated the 40% weight on the front and 60% on the back, it exposes the knee. This is improper or lazy execution and can cost you your knee if you are not careful. Be mindful of the cross kicks, and side kick attacks your opponent may throw at your foreward leg and you should have plenty of time to defend if that happens. To nullify this, train the proper weight distribution and sink your hips. This will keep the front knee rounded, arcing against your opponents thrust force.

Mobility - the stance is less mobile in circle patterns commonly found in boxing and MMA bouts. Use it for engagement purposes only, once you have crossed ‘critical distance’ and committed to your assault.

Clinch Deficient - this is not an optimal stance inside the clinch. The weight being back makes us susceptible to being pushed over backward. Once the clinch happens, shifting to the ‘weight-forward’ advantage offered by the monkey stance, bow stance, or horse stance when in the flank, is a better tool for the job.

Mechanical Breakdown

Weight Distribution - 40% of body weight on front leg. 60% on the back leg.

Center of Gravity - CG should be slightly rear of the 50/50 mark. Sink your CG by dropping your hips 3 to 4 inches. This will also bend the knees and create a suspension system in your legs allowing for better balance, and mobility.

Front Foot - aimed at target, or direction of travel.

Rear foot angle - it is imperative for stability that the rear foot be at or around 45 degrees angled off from the front foot.

Width - heel of the rear foot is in line with the heel of the front foot (see diagram).

Splitting the Floor - Focus the pressure on the pads of feet. When hips are dropped, it should feel like you are splitting the floor between your feet.

Posture - sit up straight. Shoulders over hips.

The san ti shi is an all around better stance as we can see from our strengths vs weaknesses evaluation above. The ease of use, striking power increase, kick defense capability, improved range manipulation, and takedown defense make this an optimal fighting stance far superior to the monkey stance. Therefore, it’s a no-brainer from a coaching perspective, as well as a fighter’s methodology. You can see why we switched.

6 Submission for 6 Positions - Side Control

Part of your journey in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is the transition from surviving, to defending, to getting to a dominant position. Position before submission is crucial for getting a successful submission on our opponent. But what happens when we first…

Here’s a follow-up to our popular video on the 6 Positions of Side Control Drill. Now we can apply a submission in each of these positions to help train our offensive game.

Part of your journey in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is the transition from surviving, to defending, to getting to a dominant position. Position before submission is crucial for getting a successful submission on our opponent. But what happens when we first go from surviving/defending, to continuously getting to a dominant position? Often times the brain shuts down, and we don’t have a clue what to do next. It’s important to have a gameplan.

Knowing a submission from each position, will give you a strategy to move from position to submission, or at least attempting one. Here is a companion video to go along with 6 Positions of Side Control video. Once you get that basic drill down, and you find yourself getting to side control frequently. Try this drill to learn a submission from each position and expand your game!

Mantis Captures Prey Takedowns

Trapping the elbow as our opponent shoots for the underhook. They go for the position under the arm to try and set up a variety of throws, or gain positional control. What we have lying in wait for them…

Trapping the elbow as our opponent shoots for the underhook. They go for the position under the arm to try and set up a variety of throws, or gain positional control. What we have lying in wait for them, is a potential shoulder lock if we can get it. If they dive the arm deep to save it, then we follow up with tight arm control and a solid frame as we strike with knees, and/or go for takedowns.

The following are a couple of takedowns I like to use from this position - White Ape Falls In Hole, and Monkey Goes Over Falls.

Rise from the Ruins: Embarking Into A Dying Art of Boxing

An Essay on my Early Years in Chinese Boxing Dance

Martial arts forms (kata, tào lù) are more plentiful today than in any time in history. They are widely disseminated in a variety of martial arts schools/styles across the United States, and around the world. A majority of ‘traditional martial arts’ competitions today, are centered around stylists competing with their form of choice. One is hard pressed to enter a school of karate, kung fu; kempo, tae kwon do; or tang soo do, etc. that isn’t consumed by a curricula filled with form after form. Once you complete one form, you’ve earned the ‘privilege’ to learn another...and another...and another.

Years into my training, I went on to scorn these empty shells. For quite some time actually. One reason I held such admonishment toward ‘forms’, was having…

Finding the Mantis

I came across the art of Praying Mantis Boxing in of all places - New Hampshire, USA back in the 1990’s. I was correcting course in my life and on a quest to empower myself with martial arts training and the skills to know how to handle myself. A desire of mine since childhood. I immediately fell in love with the art, even in it’s corroded state.

Sadly, time has not been kind to this, and many other Chinese boxing systems. Much damage has been done over the past century or more, as these arts were no longer used for combat. By the time I began my training, it was difficult to tell what Mantis Boxing was in its original manifestation.

What remained was largely boxing sets (choreographed fighting moves in the air known as forms/kata/taolu), myriad drills, and a plethora of archaic Chinese weapons techniques of a bygone era.

Due to this decayed state my journey early on with this art was difficult and fraught with challenges in finding answers, or seeing an effective use of these movements in sparring/combat. Thankfully, we do have those who carried the torch over hundreds of years; bringing with them the keywords of the style as well as the old ‘boxing sets’ which allow us to view into the past.

I have dedicated over 20 years to mantis boxing, as well as other stand-up fighting arts in a quest to reconstruct the art so that it is intact for my students going forward. Through traveling, studying with experts, training, competing, teaching, sparring, researching; anything I could find that would yield improvements. We move forward with methods so that others, like you, can receive a fighting art that is versatile, effective, and well…quite frankly - RAD!!!

My efforts to ultimately reshape, redefine, and revolutionize the art have created a new version of mantis boxing that is relevant for self-protection in modern times. This last part being of great import to me. I believe any martial art should be applicable and functional. Ensuring not only its own survival for future generations, but also the survival of its practitioners.

BOXING SETS

Throughout my martial arts career I have had many opinions on forms/boxing sets. These viewpoints have shifted like the swirling tides along the rock-strewn coastline of Maine. Early on, when I began my training I was heavily invested in these sets. They were, after all, the primary method of transmission for the art that I chose to study - Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳), and before that, Tae Kwon Do.

Mantis Catches Cicada - circa 1999

Mantis boxing was handed down to me by my early teachers, and their teacher’s before them, with forms as a primary method of transmission. Completely absent of the mechanical inner workings that made these moves functional with live opponents in actual hand-to-hand combat. In all fairness to the first mantis coach I had, was up front with me from the beginning about this. I was under no illusions.

Martial arts forms (kata, tào lù) are more plentiful today than in any time in history. They are widely disseminated in a variety of martial arts schools/styles across the United States, and around the world. A majority of ‘traditional martial arts’ competitions today, are centered around stylists competing with their form of choice. One is hard pressed to enter a school of karate, kung fu; kempo, tae kwon do; or tang soo do, etc. that isn’t consumed by a curricula filled with form after form. Once you complete one form, you’ve earned the ‘privilege’ to learn another...and another...and another.

Years into my training, I went on to scorn these empty shells. For quite some time actually. One reason I held such admonishment toward ‘forms’, was having learned over fifty of them in my first seven years dedicated to wu shu (martial arts) training.

As soon as I would finish one form, I would be handed another; whether by my request for some shiny new toy I was enthralled by, or a suggestion by the instructor(s). It became impossible to remember all of these sets, and far too time consuming to practice them all; little did I understand why at the time.

When it came to fighting and sparring in the martial arts schools I attended, the combative application was entirely disembodied from these forms; like a warrior’s sword detached from it’s handle - once upon a time a dangerous weapon to be feared, now - a toothless tiger.

Crossover from form to fighting never existed in the schools that I trained in. We would warm-up, practice movements, shadow box, and spar the last few minutes. When it came time to spar with classmates, it usually manifested as ‘bad kickboxing’. To be fair to these coaches, their passion lied with what they were teaching - forms, not fighting.

I kept sparring as much as possible, and competing in matches. I became increasingly frustrated over time. I would ask myself - “wasn’t the point of martial arts to learn how to defend yourself? Wasn’t the ultimate goal to become empowered? To know secret ways to disable attackers, fend off bullies, submit miscreants that wish harm upon us, or protect our families?” I was profoundly confused by the training practices I was experiencing, versus what I had envisioned martial arts being meant for.

COMBAT ARMS

Flight School - aka ‘Fight School’ - Alabama 1990

Having been in the military for a short period of my life, I was used to an environment built on training for ‘combat’. We certainly didn’t pretend to drive tanks, or fly invisible helicopters, fire imaginary bullets downrange, or use toy weapons. Lessons on my martial arts path were not adding up with my life experience. Why was a bulk of my time training, just pretending to fight opponents in the air???

While I was stationed in Texas, I briefly undertook the study of taekwondo until my military units’ training schedule was ramped up and I could no longer juggle it in. It was enjoyable at the time, but certainly wasn’t my favorite martial art style. I had a good teacher, and I enjoyed my time there (however brief), but the art was too simple, and too linear for my taste. However, to the instructors credit, in those classes we spent a bulk of our time sparring.