The 12 Strategies of a Mantis Boxer

The 12 strategies of mantis boxing are considered to be the cornerstone of this bare-knuckle clinch fighting art originating from...

A complete and comprehensive guide to becoming a mantis boxer!

You’ve seen the basics, now dive deeper with:

Extensive written supplementary material for each keyword.

exclusive videos only found here.

Curated videos to demonstrate and highlight applications.

organized and easy to navigate layout for quick access to all Of the the 12 strategies.

Over 105 minutes of HD video.

Easy to recall Strategies for applying them in combat.

The 12 strategies of mantis boxing (tánglángquán 螳螂拳) are considered to be the cornerstone of this bare-knuckle clinch fighting art originating from Laiyang County, Shandong Province, China during the latter half of the Qing dynasty. These have been handed down from generation to generation from boxer to boxer.

While the keywords can vary from lineage to lineage, with each boxer adjusting them to fit their own style and emphasis, all descendants of the mantis boxing style have a version of these keywords with the core (hook, clinch, pluck, connect, stick) in common.

In essence these are the strategies that previous mantis boxers held to be important facets of the art worthy of passing on to those who followed. They define what it means to be — a mantis boxer.

The 12 Strategies

Hook (Gōu 勾) up your opponent in a powerful Clinch (Lǒu 摟).

Pluck (Cǎi 採) them with ballistic force to take them to the ground.

Connect (Zhān 粘) and Stick (Nián 黏) to them to know their every move.

Hang (Guà 掛) to sap them of their strength and secure your position,

Use Wicked (Diāo 刁) deceptions, fakes, feints, to trick the enemy,

Enter (Jìn 進) the fray with tactical advantage to maximize success,

Crush (Bēng 崩) the opponent causing them to collapse and fall into ruin.

Strike (Dǎ 打) to knock out, stun, or distract.

Adhere (Tiē 貼) and Lean (Kào 靠) to dominate the clinch and toss them to the ground.

Deep dive into the 12 Strategies of a Mantis Boxer Today

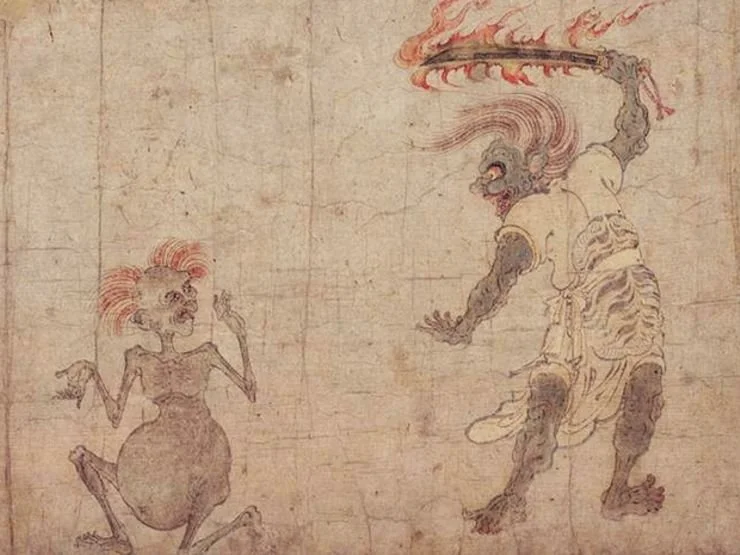

A Daemon in my Dojo

The afternoon sun turns to shadow early as the solar cycle wanes and we fast approach the winter solstice. I was finishing my training and sitting down to meditate when the visitor walked in.

A new visitor arrived in my dōjō today, a stranger from a far off land. It is the beginning of autumn in the year 2012. Dōjō, or ‘way place’ in Japanese, a place to study the way of ‘something’, typically martial arts. In Chinese martial arts we call it a wǔ guǎn (wǔshù guǎn), or martial hall, the place in which we gather for the study martial arts.

The afternoon sun turns to shadow early as the solar cycle wanes, and we fast approach the winter solstice. I was finishing my training and sitting down to meditate when the visitor walked in. Lately I have been consistently practicing meditation as a post training routine to clear the mind, to take inventory, and to stay grateful.

It has been thirteen years since I began practicing Praying Mantis Boxing (tángláng quán), and a bit over a year since undertaking the art of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (B.J.J.). I recently competed in my first BJJ competition as a newish white belt. Currently, I am training and coaching six days per week, as has been the case for the past eight years. When I’m not teaching or occasionally unfurling my wings to deftly dance off a cliff to reach for the clouds above, I pen articles on martial arts as thoughts and ideas materialize that may be of use for others on this path. I have been cross training in other arts for a few years, nothing serious prior to BJJ, but enough so that I have been experiencing modalities outside of Chinese boxing arts; seeing a broader picture.

I sit regulating my breathing, trying to focus my mind. A bright warm light washes over me as the door opens. The stranger interrupts with abrupt words that leap forth like a flash of briny sea water surging to shore on the rush of high tide. These noises flood my brain. At first I am annoyed at this intrusion, and try to ignore it for a moment of solitude. Then, I pause to listen to what he said to me.

As my mind churns over the information it feels as if this visitor is casting a bright spotlight into the deepest umbra in my brain. He begins to spout emphatically about Bēng Bù, crushing step for short, but the longer meaning is – steps to cause the enemy to collapse and fall into ruin. Bēng bù is a shadow boxing set found in styles of mantis boxing, I have been practicing this set since 2005 learning five or more versions from the various lines of mantis boxing, part of my quest to decipher the true intent behind the shadow boxing shell transmitted through mantis boxing lineages for the past one hundred years, or more. I’ve vigorously searched for the hand-to-hand combat applications originally intended by the creator(s), wanting my own continuation of this boxing style to be effective in fighting. Something I have rarely seen thus far.

Eventually I settled onto one version of bēng bù that I train a few times per week, occasionally spending time mulling over the potential applications within my head. The stranger's words snap like a bolt of lightning crackling through my mind. Riding along the spectrum of light his question crackles forth: “Why is bēng bù, like so many other Mantis Boxing forms, begun with and finished with the move, ‘Mantis Catches Cicada’?”, he continues on, “This is not a finishing move to end a fight, so why would this technique of all of them be laid out in form after form almost as bookends?”, “Is this just stylization? Is it a meaningful application?” His questions intrigue my mind, I begin chasing the lightning along its incongruous path.

Code breaking comes to mind, more specifically ciphers. I reply to the stranger, “A cipher used to crack open an ancient codex. A boxing form, in this case crushing step, a set of choreographed moves from a boxer of old, is this the codex and Mantis Catches Cicada the cipher? Perhaps this move is ‘the key’ to unlock the applications within the form?” I begin traversing the halls of the labyrinth in my mind, searching every corner, opening every door, looking at each move in bēng bù from a ‘two hooks’ (neck and arm, or colloquially known in fighting circles as a ‘clinch’ position.

The dialogue and the air around this impromptu visitor, ripple with electricity in the air. I struggle to keep pace with the trove of possibilities his questions raise. As I peruse the catalog of choreography in each road of the set, I conclude that some of the bēng bù boxing moves could certainly function from this position, but others clearly not. The questions then enter my mind, “Where is he from?”, “What, or who, is the source of visitors knowledge?”, “How did he happen upon my dojo?”. I asked his name. “Wang”, he replied.

Wang was a pesty guest, talking incessantly his entire visit. “Does he ever shut up?”, I wondered to myself silently. A wave of empathy washed over me, he did travel from afar, and spent so much time alone unable to talk to anyone about this subject matter. A topic that must be yearning to escape the prison of his mind.

Wang spoke day and night, following me home after classes. He had nowhere else to stay on his visit, I felt compelled to open my home to him, annoyed at times, but grateful for his illuminating thoughts and inquiries.

During his stay I rarely caught a wink of sleep. Wang sat next to my bed at night incessantly rambling till the sun came up. With no choice I lay awake listening to the chatter, staring at the ceiling, throwing off the sheets in exasperation, pacing the room, and spending nights shadow boxing while Wang rolled on. I caught a wink of shuteye here and there, only to rise early again the next day. A true insomniac, Wang did not sleep, obsessed with his ideas which spawned forth like seven hundred baby mantids hatching from an ootheca in the midsummer garden.

With seemingly nowhere else to be, Wang stayed for weeks, revealing a series of mantis boxing positions and hand-to-hand combat applications I had never considered before. I immediately went to task testing these in drills, sparring, and grappling as Wang sat looking on in satisfaction. A new world arose around me; a schism manifested, a cataclysmic shift in my worldview of fighting.

Wang, seeing my progress, bid me farewell for the time being, proclaiming as he exited my dojo, “Perhaps I’ll return, but for now, you need to chew for a while before we can dine again.” I bowed to Wang in gratitude, and wished him well on his travels. Thus concluded my first visit with the daemon who sojourned to my dojo.

Discovering the 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing

The above short story is an allegory based on real events. An episode in my life back in 2012 consiting of an explosion of ideas and thoughts. The dōjō is not the one I train and coach inside night after night, but rather the one I spend far more time in, the one inside my mind.

My daemon, Wang, is based on Wang Lang the mythical founder of mantis boxing. The man accredited with the origin of this boxing style hundreds, or thousands of years ago, depending on who you listen to. You can read more about Wang Lang in an article I wrote on his possible accreditation to the art here: The Apotheosis of Wang Lang

Prior to this experience I had little in the way of instruction or conversance with the 12 keywords of Mantis Boxing. I certainly knew of them, as most serious and long term practitioners of the art do, but I had yet to delve into them. From my observations and experiences any information regarding these keywords, and conversations surrounding them amongst mantis boxers and coaches, devolved into arguments over what the ‘correct’ keywords are, and their true meaning.

The thoughts I had on ‘mantis catches cicada’ were real. However, while this was a ground-breaking revelation that sparked an age of discovery, and helped lead me onto a fruitful path, years later I debunked this theory when my research exposed mantis catches cicada as nothing more than a — brand moniker, rather than an actual fighting technique. A mantis boxing en garde to proclaim, ‘We do mantis.’ This moment in time though, when all these thoughts began to appear, shifted my brain into thinking of each move from a whole new pillar of fighting — wrestling/grappling.

My daemon helped me to see the first three of the twelve keywords of mantis boxing with new eyes. I began to commit pen to paper, to record these thoughts as they manifested. It crawled from my pores with an unstoppable force. We took photos. I wrote my first quasi-article on ‘What is Praying Mantis Boxing’, now titled The Heart of the Mantis, a rough experience. This idea that wrestling was an integral part of mantis boxing was scoffed at by the mantis boxing community, and some were extremely rude in their rebuttals. I charged forth anyway, fully committed and stalwart in my belief that I was on the right path. As with any new endeavor, I was getting my legs under me as I awoke from a slumber.

Over the ensuing years Wang would come by for a visit from time to time. If I was not paying attention he would splash hot tea on my brain, burning me so I would once more bring my full attention to bear on what he had to say. As I continued boxing, grappling, and progressing in BJJ I unlocked more and more positions and fighting applications. An increasing number of the keywords unlocked before my eyes.

I noticed a similarity with other grappling arts and recalled Gichin Funakoshi remarking in his book Karate-Do that I read back in 1999, that Kara-Te (way of the Tang Hand) was a blend of techniques Okinawan nobles would bring home from southern China during the Tang dynasty, and blend them with their indigenous fighting arts. Years later finding out those indigenous arts were wrestling.

As we sat in the garden sipping tea on one of Wang’s visits, he asked me: “What were China’s indigenous fighting arts?” I began to delve into the history of the Chinese martial arts ecosystem as a whole, coming across...Bokh, the Mongolian wrestling arts still alive to this day. This was enlightening especially since many techniques looked similar to postures found within Mantis Boxing (and other styles) forms of Chinese martial arts that I had studied over the years, to include: taijiquan, eagle claw, long fist, and more.

Bokh, and its history/influence on Chinese culture when the Mongols invaded and took over China during the Yuan dynasty, made me grossly aware that Mantis Boxing along with other Northern Chinese Martial Arts styles that I had studied over the years, contained a great deal of stand-up grappling, or wrestling. This realization has evolved over time as my understanding has grown, now aware that the Manchu were heavily vested in wrestling culture, ruling China for over 250 years during the Qing dynasty; the last of the dynastic eras of China. From there a growing realization of Han wrestling, jacket and no jacket wrestling from the Shaanxi, Shanxi provinces, along with a broader understanding of how much wrestling was part and parcel to so many cultures the world over, almost integral to our DNA as a species.

I could now see that a bulk of these ‘systems’ from northern China seemed to revolve ‘around’ grappling as a primary pillar, using methods and tools to facilitate ways to clinch and grapple an opponent, to throw or trip them to the ground.

The other primary art I trained and taught at the time of writing the above essay, was Taijiquan, specifically Yang family style which was originally known as small cotton boxing. The principles within that style also screamed grappling and I began to dig into the 13 keywords of Taijiquan, performing a comparative analysis of mantis boxing and supreme ultimate boxing after finding so many parallels. This is a working document that I return to from time to time over the years - Brothers in Arms: Mantis Boxing versus Supreme Ultimate Boxing

Arriving at ‘my’ 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing

Hook, Clinch, and Pluck were the first lessons from Wang Lang. These were followed by Lean. Lean was particularly elusive at first simply because myself being a striker/kicker I failed to see why we would want to lean in a fight, only to give our opponent a shorter distance to hit us in the head. Once applied to grappling and the close distance fight, leaning becomes integral to our survival.

The other keywords were increasingly harder to unravel, with growing absences between visits from my daemon. Long arduous periods of contemplation and frustration, times where I would continue to ask questions into an endless vacant void. From time to time though, my daemon would once more return, once more shredding the thick overgrown vegetation of confusion with razor sharp claws.

Once I could see through the adeptly graven undergrowth, and light shine upon the darkness once more, new techniques would reveal themselves. Eventually, a keyword, or two, would whisper from the lips of my daemon and wisp through the tattered leaves in the garden.

Adhere was the next to become apparent, especially due to its significance in BJJ, where controlling, or consuming space from an enemy while grappling on the ground was so significant. The same was true in stand-up grappling.

Strike was not as simple as it seemed. Ultimately, it is simple ‘to hit’, but why would something so obvious be a keyword? My daemon laughed at me, “If you don’t strike as you Enter, you’ll meet your doom.” he said. “If you do not strike to Connect, you will fail to find your enemies limbs, and meet their fists as you arrive.” “If you do not strike in the clinch, be prepared to receive…injury!”, he laughed harder.

Connect & Stick were the next keywords to be codified. Wang Lang, ever the sarcastic ethereal daemon, made disgusting references to gum, saliva, and the various stages of sticking, to bring these epiphanies to life. “That’s the easy part, but knowing when and how to use them without being punished is another issue entirely.” Offensive application versus defensive utilization was worthy of deep study, otherwise a broken nose would ensue.

Beng, to collapse and Fall Into Ruin came to me in the garden one day. Wang Lang was hanging out on the branches of my kale plants attempting to capture unsuspecting wasps, butterflies, and bees. As his hook snapped out to strike an unsuspecting passerby, he did not crush this victim with his deft strike, but caused it to collapse and fold in upon itself, crumbling to the ground below.

Beng was such a loud lesson that I had to write an article for it and publish it in a magazine for all to see. The idea that causing the opponent to collapse and fall into ruin using various methods, was revelatory to say the least. Especially since one of the core forms of mantis uses this in its name.

Wicked, or in other words, to be ‘sly, deceitful, or tricky’. Wang Lang just flat out hit me over the head with a heavenly strike on this one. What is a fake, or feint when boxing, if not a ruse to open up the opponent and land a strike? A loud noise, bang, or yell - are they not a diversion to enrapture our opponent for a brief moment so that we may gain unfettered access to enter and annihilate them? The use of pluck to force an opponent in the opposing direction of our throw, trip, or takedown, gain freedom to adhere and lean as we barrel forth into a takedown; is that not beguiling?

Wang Lang was rather condescending on that last one, especially since I had been using these tools for years yet failed to see the connection to the keyword he left etched in history.

Hang was another slap on the head, or ‘duh’ moment. Hang was pointed out by my daemon genius spirit. He vaingloriously proclaimed to me - “If you don’t root, lower, ‘hang’ on your adversary when engaged with hooks in the clinch, you’ll get tossed and trampled like you tried to wrestle an elephant!!!”

The Keys to the Style? Or Keys to the Stylist?

The 12 keyword formula of Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳) houses the principles that help define the art. These characters, or variations of them, have been passed down through the common vernacular of Chinese boxing methods in northern China. While not unique to mantis boxing, and evidence of their existence in other styles of the region and time period exist, they can establish a definitive strategy for mantis boxers; much more so than a collection of tao lu (forms) that have no consistency from one branch of the style to the next.

Replication of these keywords does exist among the various lineages of mantis boxing, especially in the first few keywords. No matter the style, many of the more obvious in name keywords such as: Strike, Crush, Hook, Enter, Lean, Clinch, Pluck can be witnessed in Mantis Boxing forms. Those which are harder to mimic in the air - Connect, Stick, Adhere, Hang, and Wicked, are absent in the forms from all indications, and are found rather through live training and sparring practice.

Many of the grappling specific keywords exist in various forms of martial arts still alive today. Although lost within Mantis Boxing lines, one needs simply look at other unarmed combative styles to find evidence of not only their existence, but also significance when it comes to fighting.

An art, of any type, is not defined by hard and fast rules, but is open to interpretation and adaptation by the artist. Keywords of a style, or system of boxing, are a series of principles to guide the practitioner. The definition of these principles and what they mean is highly variable and intimately related to the boxer using and/or coaching them.

The keywords can change from boxer to boxer, allowing for wide adaptation and freedom of expression, and each boxer can select which they rely on more than others. As long as the boxer adheres to a loose framework which includes the hook and pluck keywords, as well as the connecting and sticking specifically, then the stylist is still manifesting an art which mimics the fighting traits of the praying mantis.

These 12 keywords I pass on represent the foundational core of my mantis boxing art. Which strikes, kicks, throws, trips, submissions, you choose to use when you fight can vary widely from my own. And yet, with common principles we bond together as martial artists, share, and reward one another’s successes.

It took me six years to unlock what these keywords mean to me. Use them to discover your own methods. Keep what is valuable to you, discard what is not. Practice with it, fight with it, and your own truth will be one day be revealed to you. Validity in martial arts is not established by the opinion of others, but rather it is, and should be, measured by the success of the actions and execution of our methods.

To learn more about my 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing you can find a course I have available that combines video instruction with more detail in written explanations and descriptions of each of the 12 keywords.

Research Notes (Open): Power Building Boxing (功力拳, Gōng Lì Quán)

Gōng Lì Quán is a unique boxing set from northern China that is found included as a training routine amongst a variety of boxing styles in the north, to include, long fist, eagle claw boxing, and praying mantis boxing. It likely mixed with the latter two styles when it was included as….

Gōng Lì Quán, or Power Building Boxing is a unique boxing set from northern China. It is included as a training routine amongst a variety of boxing styles in the north to include: long fist, eagle claw boxing, and praying mantis boxing. This form likely intermixed with the latter two styles when it was included as part of the Jīngwǔ Athletic Association’s fundamental wu shu curriculum.

At Jīngwǔ, gōngliquán was one of six mandatory ‘empty hand’, and four ‘weapon’ sets taught to practitioners. These ten sets were required as a prerequisite to the study of other styles of Chinese boxing: xingyiquan, bagua, taijiquan, eagle claw, or mantis boxing; considered by Jīngwǔ founders to be more ‘advanced’ styles.

MY FIRST INTRODUCTION

I first came across gōnglìquán whilst studying Eagle Claw Boxing back in 1999/2000. Although it often is, Gōnglìquán was not included in the style of mantis boxing I was learning at the time, but it was my introduction to Eagle Claw Boxing. This was the first version of the set I learned.

The research I’ve done on this set over the years has predominantly been focused on the physical execution of the movements, the variations of the boxing set from one style to the next, and the combat applications of the movements within the set.

Back in 2006 I delved deeper into gōnglìquán with the intent to reverse engineer the combat applications. Gōnglìquán was passed on to me as an empty shell, a form of shadow boxing or choreographed series of movements, as was most of my early Chinese boxing.

At the time that I first attempted to figure out the secrets hidden within the set, I lacked the knowledge and skill to properly dissect it, my expertise at the time was rooted in striking, kicking, and submissions (qin na), not wrestling, or grappling.

In attempting an analysis of this set however, I learned eight different versions, comparing and contrasting each set with one another with the goal of keeping the redundancies, while eliminating anomalous moves that were likely performance based rather than combative.

We set about at translating a couple of books on gōnglìquán, with one of my students Adria Kyne handling the linguistics, Adria could speak and read Mandarin so her expertise was invaluable. Since most of the text was written in ryhme, or verse, relevant to one ‘in the know’, these translations were sadly of little benefit in unlocking the true intent behind these moves at the time. As years passed I kept practicing and teaching the set up until a final seminar I taught in 2012.

TRIM THE FAT

Since 2012, I’ve rarely turned an inkling of a glance in the direction of gōnglìquán. I no longer train or teach forms, my time is consumed with fighting application and sparring which I find much more rewarding and a far superior vehicle for teaching the arts to others. Gōnglìquán became a distraction from my work on mantis boxing sets, keywords, and taijiquan combat applications so I left it on the side of the road while I traveled on.

However, a recent discussion began weeks back in a pub in Wales, UK between another high level Chinese boxer and myself as we bombastically tossed one another around the bar sharing techniques. The conversation has continued since via back and forth emails, and as such has brought my attention back to this boxing set I left behind so long ago.

Our didactic discourse has included many subjects in the field of Chinese boxing, but repeatedly returned to the element of Chinese wrestling transmitted within these boxing sets. If a reader is not yet aware of the level of influence folk wrestling has had on the formation of these boxing sets passed down for over a century, then you are in for an amazing discovery.

THE WANDERING WARRIOR

During the pandemic, Vincent Tseng (Black Belt - Mantis Boxing) began his deep dive into gōnglìquán while he was locked down in Taiwan and studying Shuia Jiao there. Vincent reached out to me at the time on his rekindled interest in the set, and we discussed the high probability of the set being wrestling-centric. I supported his endeavors and Vincent went to work on forming his own analysis of gōnglìquán that you can find on his YouTube channel — The Wandering Warrior.

While Vincent and I did converse on his project at the time, and he graciously shared his videos with me, which I thought were excellent, I was in full on survival mode at the time trying to keep our team training remote, building online courses, streaming classes, and meeting everyone’s needs, while at the same time rehabbing our derelict house. My attention to Vincent’s work while committed and sincere, was short lived. At the time I was also tearing apart (again) Beng Bu and Luan JIe, two of the core boxing sets from mantis boxing and re-interpreting their techniques. My headspace for reverse engineering combat methods from forms was 100% devoted to these sets.

Since picking gōnglìquán back up for the reasons I’ll list next, I have specifically avoided revisiting Vincent’s extensive work with the purposes of avoiding any cross contamination of our different analyses. Once this project is complete I plan to go back and revisit Vincent’s work and compare commonalities to see where our interpretations intersect.

REKINDLED INTEREST

My new friend Graham Barlow of The Taichi Notebook has a background in Xingyiquan, Taijiquan, and Choy Li Fut, a southern style of Chinese martial arts, as well as a black belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Thus we can speak seamlessly on Chinese martial arts, BJJ, and grappling/wrestling. In one of his styles, Choy Li Fut, there is what some practitioners refer to as choy li fut’s ‘signature move’: sau choy. A similar move to this is found inside gōng lì quán, what we call 3 Rings Trap Moon. As Graham and I talked I took another look at the set with the knowledge and eyes I have now. Some new and intriguing ideas on the combat applications came to light, and it would appear the entire set consists of wrestling moves, which is counter to any translation I or others have attempted in the past.

It is important to remember that sets like this were a vehicle or storehouse for a boxer’s system of moves. Many boxers of old spent a bulk of their practice time alone. The set’s name translates as: power building boxing. One practicing the set uses the movements within to train the creator’s boxing techniques in a manner akin to exercise, a creative way to transmit the movements to others without reading and writing; skills which were rare at the time. The use of hyper low stances, calisthenics, exaggerated movements, and dynamic tension, allow for a self contained training system alongside a library of techniques.

Below are videos with one of my black belts Tom McNair. We began with shooting a couple of videos (Double Bump, or Punch, and Three Rings Trap Moon) to highlight the ‘stylized’ shadow boxing move juxtaposed with the ‘weaponized’ combat application. Enjoy.

UPDATE: Since starting this mini project, it would appear another daemon has decided to drop by my dojo for summer break. I’ve been unable to turn my attention away from the set and keep unmasking the combat applications previously hidden before my eyes. So for the meantime, at least until this welcome, but uninvited guest leaves town, we’ll be releasing more of these videos, possibly the entire boxing set. This weekend I’ll be adding Twining Silk Legs, Lock Neck Through Sky, and Pluck Eggplant.

Stay Hooked!

Gōng Lì Quán Videos

Tyrant King Lifts Ritual Tripod | Throw in Well

Coming soon…

Horse Dragon Deep Sea

Coming Soon…

Collide Elbows, Double Bump

Twining Silk Legs

Lock Neck Through Sky

a.k.a. — Sweeping Moon Off The Wind Over Clouds, and Overturn Sack. This move is executed with slight variations from version to version. Here we depict Lock Neck Through Sky and Overturn Sack variations.

Cast Off Hand/Capture Hand

Next Up. Stay Hooked!

Pluck Eggplant

This move is another counter to the counter when committing to 3 Rings Trap Moon attacks. Rather than stepping back, the opponent steps around the leg to maintain position.

Three Rings Trap Moon

Make Coil Squeeze Pound/Lock Neck Carry On Head

Up Next. Stay Hooked!

Slant Chop aka Single Whip

Up next. Stay Hooked!

Gōng Lì Quán Boxing Set Demonstration (Tao Lu) - 2012

Gōng Lì Quán Boxing Method

Tyrant King Lifts the Ritual Tripod

Letter Hand Throw in Well

Bow Stance Horizontal Fist

Horse Dragon Deep Sea

Letter Hand Throw in Well

Horse Dragon Deep Sea

Double Cross Waist

Double Bump (L)

Collide Elbows, Double Bump (R)

Lock Neck Through Sky

Twining Silk Leg (L)

Twining Silk Leg (R)

Collide Fist

Cast-off Hand

Pluck Eggplant

Collide Fist

Cast-off Hand

Three Rings Trap the Moon (R)

Three Rings Trap the Moon (L)

Three Rings Trap the Moon (R)

Three Rings Trap the Moon (L)

Collide Elbows, Double Bump (L)

Collide Elbows, Double Bump (R)

Collide Elbows, Double Bump (L)

Cast off Hand

Capture Hand, Collide Fist, End Cast-off Hand

Make Coil Squeeze Pound

Lock Neck Carry On Head

Cast-off Hand, Collide Fist

Capture Hand, Collide, Fist

Slant Chop Fist

Jump step, Clap Palm, Collide Fist

Pierce Palm

Servant Stance Navel Eyebrow Palm

Pierce Palm

Collide Fist

Translating ‘Fist’ (Quán 拳)

As Chad Eisner points out in his translation of Qi Jiguang’s treatise on unarmed combat found on Judkin’s Kung Fu Tea blog, the character ‘Quan’ 拳 is used in various ways, especially when discussing Chinese martial arts. At times it is used as ‘fist’ and at other times as ‘boxing’. When used in conjunction with other characters such as in this case Gōng 功 and Lì 力, it more specifically refers to a system of “unarmed techniques/combat” which denotes anything from striking to kicking to grappling or wrestling techniques. It is not confined to punching.

Gōng Lì Quán Grappling ‘System’ Breakdown

The following is a breakdown of the moves within the choreographed set, categorized by technique types found within the Gōng Lì Quán ‘system’. I now refer to it as a system after discovering the inclusion of: ji ben gong training (fundamentals), grip defense, combined with the series of throwing/tripping/sweeping methods embodied in the form. Gōng Lì Quán by all indications is a self-contained training system for the creators’ grappling/wrestling methods.

“When our only tool is a hammer, every problem is a nail.”

Any instances of what appears as a strike or a kick found within the set, can be dismissed with almost complete certainty as being a punch or a kick. These techniques used in such a manner would prove to be disastrous in a real fight.

Upon deeper examination of the set through the lens of grappling methods common to the region, each move can be explained and shown to be effective wrestling methods. Many of these techniques still exist in shuai jiao as well as other wrestling arts found in China and surrounding cultures.

Grips, Grip Defense, & Jibengong

These are techniques centered on deflection, parrying, blocking grip attempts, and/or breaks.

Tyrant King Lifts the Ritual Tripod

Letter Hand Throw in Well

Bow Stance Horizontal Fist

Horse Dragon Deep Sea

Double Cross Waist

Cast off hand

Capture hand

Throws, Trips, Sweeps

Collide Elbows, Double Bump

Lock Neck Through Sky

Twining Silk Legs

Collide Fist

Pluck Eggplant

Three Rings Trap Moon

Lock Neck Carry On Head

Slant Chop

TBC…

Gōng Lì Quán Historical Record

Anyone with more information on the roots of Gōng Lì Quán is welcome to email me, or leave a comment below. Your contributions will be greatly appreciated and added to the post with accreditation.

While little in the way of solid facts exist around Gōng Lì Quán’s origin prior to Jing Wu, there are numerous oral sources naming Cangzhou, Hebei as the place of origin. Some sources claim it arrived on the scene early in the Qing dynasty, but this is uncorroborated. Of note is, Cangzhou being central to Baoding and Tianjin, both major Chinese wrestling centers throughout several dynastic periods in China’s history.

The Taiping Institute lists over 33 styles of empty hand and weapon sets they claim originate from Cangzhou. Gōng Lì Quán being among them. There are no sources listed for these attributions so it is difficult to know if this is revisionist history, or if Cangzhou is actually home to a large number of Chinese martial arts ‘styles’ that have survived till modern times; if survival includes the empty shells known as forms (tao lu).

NATIONAL STRENGTHENING & REFORMATION

As is well documented at this point in martial arts scholarship much of modern Chinese martial arts was changed, morphed, and re-appropriated from fighting to physical education as part of the nationalist efforts of the government of China in the early twentieth century, with the goal to strengthen her populace after repeated humiliations with the west — lost wars with western and eastern powers, corruption, disasters, famines, rebellions, and drug epidemics.

Amongst these efforts was the creation of institutes chartered with the task above, and modeled after and in direct competition with the YMCA. Jing Wu was one of these institutions. At the inception of Jing Wu they included a revamped Chinese martial arts as part of the curriculum, alongside many other sports and activities with the express goal of physical education.

Tasked with establishing a curriculum to represent the nation’s martial arts, and attempting to consolidate over 100 or 100’s of styles, it is my view that they initiated a ‘culling of styles' in an effort to represent this diverse kingdom in a manageable way. Many of these styles: red boxing (hongquan), plum boxing (meihuaquan), ba ji, power boxing (gongliquan), etc etc etc) contain a common vernacular of movements, making a strong case for why they were excluded.

If a style did not stand out as 'unique', or have a strong brand or history already attached to it (mantis, eagle, bagua, xingyi, taiji), it is easy to believe it was chopped up for parts. Whereby similar movements found to overlap other styles tossed into a larger bucket of ‘Northern Shaolin Long Fist’, or an overly simplified North/South context. Simplifying a convoluted and confusing history that was not relevant to the government's purposes, or in line with the mission at large.

Fast forward to the 1950s and this categorization was further propagated and reinforced by the PRC when they created modern Wushu and the creation of standardized sets (forms) being bundled into long fist and southern fist. It is plausible to see why gōnglìquán, a set from Cangzhou, if the oral accounts are to be believed, with large extended movements similar to other longfist-style movements, was included alongside other styles from the north. Add to this that gōnglìquán does not have a significant number of unique techniques, roughly sixteen moves, making it even easier to include it in a broader system, especially when some of these same moves are found in taijiquan, tanglangquan, and yingzhouquan.

EMPTY SHELL WRESTLING

By the time of Jing Wu’s creation it is possible the fighting applications of the techniques within gōnglìquán had already been lost to time making the boxing set even less distinguishable from other routines.

Of interest is, Jing Wu had a wrestling program independent of these basic wushu routines. This leads me to further believe that the combat methods of gōnglìquán were already lost, although it is possible it varied enough from the wrestling curriculum that whoever dictated that program’s training regimen had a distinct bias for an altogether different style of Chinese wrestling. The intriguing question is: if the combat methods inside the form were still known, why would a fighting form full of wrestling moves from Cangzhou, be taught without…the wrestling?

PERSONAL PROJECTION

If one throws out all of the included evidence that points to gōnglìquán being comprised of wrestling moves rather than strikes and kicks, and disagrees with the video demonstrations above, if gōnglìquán truly is not wrestling, meaning that I am only projecting my own knowledge, experience, and research onto this set with revisionist intent, then we have an incredibly strong argument that this set would fall under the experiences of General Qi Jiguang and other author’s survey of Chinese boxing styles during the Ming dynasty -

“These flowery styles had lost the foundation of boxing and strayed very far from some presumably simple and original form.“

The reason being, none of these techniques stand up to battle testing in a boxing and kicking context. A bevy of examples found in books, videos, YouTube, over the past 30 years or more, demonstrate these moves being applied as such. Each and every example under careful scrutiny fails to stand up as effective in real fighting vs fantasy boxing, or kung fu movie fighting.

Anyone using these techniques as strikes and kicks will meet with utter failure even against novice street fighters or strongmen, never mind seasoned fighters and grapplers from other styles even within regional borders, and across the globe.

NORTHERN SHAOLIN MYTHOLOGY

In modern writings gōnglìquán is categorized as being a “Northern Shaolin”, and/or “Long Fist (chang quan)” boxing set. It is more likely that this inclusion amongst Shaolin is part of the overarching oversimplified duality of Shaolin versus Wudang, or Northern styles versus Southern styles classified early in the twentieth century and later reinforced by the People’s Republic of China in the mid twentieth century.

The Shaolin Temple is 416 miles (617km) SW of Cangzhou. Essentially equivalent to a trek from Boston, Massachusetts to Washington D.C. There is a significant distance between these areas. Although it is too easy to assume zero to low probability of boxing and wrestling pollination between such great distances in the 1800s. Reflexively we think of things in modern day settings where a majority of us would never dream of walking 416 miles to get to a destination. We think of travel in terms of automobiles, trains, and planes, failing to recognize that humans have been far more migratory as a species for thousands and thousands of years, and the 1800’s was well traveled.

China is no exception. It is impossible to rule out that someone from Shaolin traveled to Cangzhou and disseminated their martial knowledge there. However, Shaolin was not known by us for wrestling, gōnglìquán is not recorded as being taught at Shaolin, and Cangzhou has both wrestling, and gōnglìquán as part of its heritage. Peter Lorge in his book Chinese Martial Arts From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century dispels the excessive credit and significance of Shaolin’s influence on China’s martial arts history as a whole, citing a 900 year gap in Shaolin even being mentioned in regards to martial arts, and only reappearing in the Ming dynasty when they help battle pirates — with weapons.

Lorge goes on to elaborate that the connection between Shaolin and martial arts was becoming more prevalent during the Ming. Lorge also makes clear that the focus of these martial arts was predominantly based on weapon combat rather than unarmed, as weapons were more effective at defending Shaolin’s lands and assets. Furthermore, he points to temples such as Shaolin being refuge for travelers on their journeys, where it would be more likely techniques were brought here, or learned here during someone’s stay.

We can conclude that while not improbable for someone of the time to travel to pick up fighting methods and disseminate those in another region hundreds of miles away, the gōnglìquán Shaolin origin falls apart when we compare the histories and styles of both areas, look at the types and methods of combat being transmitted in each, and fail to have any substantial evidence of gōnglìquán existing at Shaolin, not even oral records.

Jīngwǔ

Jīngwǔ was created in 1910 as part of a national reformation movement. This was another attempt at using Chinese martial arts to help combat a weakened populace and culture. Chinese martial arts were not viewed highly prior to this, in part due to the humiliating defeat of the boxers vs the western powers during the Boxer Uprising. Chinese martial arts was often tied to nefarious groups with less than noble intentions. This is an oversimplification of an intricate and complex problem with many tendrils attached. The purposes here are not to rehash the history of Jīngwǔ, or the Boxer Uprisings, but to trace gōngliquán’s path to modern times. I’ll end my commentary on the wider implications with another quote from Ben Judkins:

“This basic social pattern started to undergo a fundamental shift in the wake of the Boxer Uprising (1899-1901). In the modern era (dominated by firearms) the original military applications of the martial arts started to look outdated to a number of educated social elites. Actual military and police personnel had reasons to continue to be interested in unarmed defense, but these sorts of concerns rarely bothered arm-chair reformers or “May 4th” radicals. In fact, many of these reformers and modernizers wanted to do away with traditional hand combat. To them boxing was an embarrassing relic of China’s feudal and superstitious past.

For the martial arts to succeed in the 20th century they would need to transition. They had to be made appealing to increasingly educated and modern middle-class individuals living in urban areas. It would be hard to imagine a group more different from the rural farm youths that had traditionally practiced these arts. But this is the task that the early martial reformers of the 20th century dedicated themselves to.”

NOTE: If a reader is interested in a deeper understanding of the time period where Chinese martial arts transformed from a fighting art to a form of physical education, commercialization, and a coupling with more esoteric and religious practices, I highly recommend reading Joseph Esherick’s ‘The Boxer Uprisings’ for a better understanding of the late 1800’s into early 1900’s China. For extensive detail on what would become The Republican Era, and the Nanjing Era, I recommend the plethora of articles written by Ben Judkins in his prolific blog Kung Fu Tea. The references at the end house several sources that can satisfy your thirst for knowledge.

Jīngwǔ had a large charter when it came to fitness, Chinese martial arts was only a part of it. The YMCA is truly the best comparison as a member could take up tennis, fencing, wrestling, etc etc etc. When it came to martial arts though, Jīngwǔ had a basic curriculum and then an advanced track. The martial arts were taught as forms (taolu) and combatives/sparring were not the focus. The goal was fitness and exercise.

Their directive was noted in an English article published in the Jīngwǔ 10th anniversary journal:

“Ten years ago [1909] when the Association was founded, the press and the general public criticized and called it a place for breeding “boxers.” The gentlemen interested, however, were not discouraged, knowing the need of physical culture for the 400 million and the value of “kung fu” as gymnastics.”

Gōngliquán was one of six mandatory ‘empty hand’, and four ‘weapon’ sets taught to practitioners before they could advance. These ten sets were required as a prerequisite to the study of other styles of Chinese boxing: xingyiquan, bagua, taijiquan, eagle claw, and mantis boxing; considered by Jīngwǔ founders to be more ‘advanced’ styles.

When assembling the curriculum for Jīngwǔ, Judkin’s writes:

“the institutional structure of the modernist Jingwu Association tended to absorb sets from various arts rather than presenting them as distinct, self-contained, lineages.”

While I am still searching for more information on the curriculum development for the martial arts program at Jīngwǔ, and specifically why each set was chosen, we can see that gōngliquán was obviously chosen, and did not have a Shaolin heritage that was necessarily tied to it. Nor was it the purpose of Jīngwǔ to promote this narrative as seen in Tse’s writing about Ying Hon Lan’s research, and Andrew Morris’ book on this period:

“Yin details how the martial arts were at their lowest ebb during the 1900s due to successive failures on the battlefield, the Boxer Rebellion, and the elimination of the Imperial martial examination in 1901.17 From this low point, Yin describes how martial arts became a sport discipline in schools and in the standing armies of various warlords by the 1910s and 1920s.

This work is one the first to draw extensively from the primary sources within the Republican Era Guoshu Periodicals Collection. Yin uses a variety of primary sources to recreate the rich martial arts milieu in Republican China, while the roles of martial arts as a form of physical exercise (as promoted by the Chin Woo Athletic Association) have also been covered in Andrew Morris’s Marrow of a Nation.”

Performing a quick internet search of ‘Shaolin gongliquan’ finds a plethora of martial arts schools claiming the set to be Shaolin while coincidentally reproducing the exact or near simulacra of the basic curriculum of Jing Wu established in Shanghai in the summer of 1910. This attribution to Shaolin or longfist is extremely tainted, and is by all appearances being revised onto Shaolin, not by Jing Wu, but rather the later division of Chinese boxing into Northern & Southern styles established by the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Guoshu Institute in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s.

Modern kung fu practitioners continue this cycle of syncretism by selling a story of a wrestling set from Cangzhou with no connection to Shaolin or longfist (changquan), as being an art that is now Shaolin, or ‘northern long fist’, while presenting absolutely zero evidence of this being true. Simply a regurgitation of a narrative built 100 years ago to suit the purposes of a government organization of the time.

The inclusion of the above historical detail on Jīngwǔ is important to our purposes as it establishes the official written record of when gōngliquán appears on record, how it connects to other styles such as eagle claw and mantis boxing, and the critical aspect of — Chinese martial arts at-large, but specifically the forms found in Jīngwǔ, no longer being taught with martial application included. Rather instead, strictly taught as exercise sport. With this established we can focus on how a style known as changquan came to be, and parse out if gōngliquán is, or is not, a part of this style.

CHANGQUAN (LONGFIST)

Longfist has a separate and congruent history alongside gōnglìquán, with some claims linking it back to Emperor Taizu of the Song dynasty (960-1279). General Qi Jiguang in his 1560 survey during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) mentions: “Taizu’s stances of the long fist”, but the reference is to ‘stances’ not a style, or even fist methods.

There is a bottomless void when it comes to searching out any real scholarship that has been done on the history of this style. In all likelihood this is due to it being fabricated as a ‘style’ in the early 1900’s as part of the reformation movement. Of note is that, a majority of the narrative is espoused by lineages linked to Han Qing Tang and the Nanqing Guoshu Institute which we’ll cover later on.

According to the changquan Wikipedia page the actual historical term can only be traced back to the second half of the 1800’s, coincidentally the same time other styles of boxing in China began to revise their histories and/or brand themselves. This is when we also see an explosion in the commercialization of Chinese martial arts. A quote from the wiki page points to this much later creation of longfist:

“The Long Fist of contemporary wǔshù draws on Chaquan, “flower fist” [sic meihuaquan], Huāquán, Pao Chui, and "red fist" (Hongquan)”.”

This helps make a case that the ‘long fist’ style was born out of the Nanqing Guoshu Institute and is not an ancient style that existed from the Song dynasty. It also explains why these other styles that are the formation of longfist, and popular in the Qing dynasty, disappeared or at the least, lost substantial popularity and flirted with extinction. Post Nanqing Guoshu Institute is when we see the shell of the northern Shaolin as a system arriving on scene, and gōnglìquán now included as a part of this style.

TAIZUQUAN

There is a style called Taizuquan which still exists today, but it lacks any mention of a set known as gōnglìquán while mentioning many others. A quick review of the wikipedia page on Taizuquan, summarizing the bare-hand sets in the style, shows an absence of gōnglìquán. There’s little point in this research to delve further into this style as it has no bearing on gōnglìquán.

SHAOLIN BURNING - THE CENTRAL GUOSHU INSTITUTE

The Nanqing Guoshu Institute is important in establishing when, where, and why I believe gōnglìquán ended up being classified as Northern Shaolin Longfist.

Albert Kayter Tse writes in the opening paragraph of his dissertation — Unfulfilled Potential: The Central Guoshu Institute in Republican China 1928-1948:

The Central Guoshu Institute 中央國術館 (1928-1948) in Nanjing was a martial arts entity funded by the Nationalist government to ‘promote better physical health to the population through martial arts practice.’ With its prestige and funding, the Central Guoshu Institute opened a nation-wide network of martial arts schools, held two national marital arts tournaments, published books and journals researching and preserving martial arts, participated in exhibition tours of Southeast Asia and the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, and trained a new generation of martial arts masters. In 1937, with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war, the Institute relocated several times before disbanding in 1948 on the eve of the Communist takeover.

1928 to 1938 is known as the ‘Nanjing decade’, a period in the Republican Era of China’s history. Before we go further let's establish a few facts:

1911 - Jingwu was created in 1911 in Shanghai and later opened a branch in Hong Kong. Gōnglìquán is included in the curriculum.

1927 - Shaolin temple burned.

1927 - 1950 - Chinese Civil War

1928 - Nanjing Guoshu Institute created. Later includes Shaolin styles in its curriculum. Gōnglìquán is not included in the curriculum of Nanjing Guoshu Institute.

1937 (technically 1931) to 1945 - Second Sin0-Japanese War, also known as World War II.

The Shaolin temple burned to the ground in 1927 under orders from Chiang Kai Shek, leader of, at the time, the National Revolutionary Army and after 1928 the leader of the Republic of China. The head abbott of the temple gave sanctuary to his friend, a rebel general fighting against Chiang’s Northern Expedition to reunite China. After losing he fled to the temple seeking refuge. According to records, when Chiang’s soldiers arrived to rout the general, the monks of the temple fought back, losing to superior firepower. Chiang’s general ordered the temple burned and Shaolin history and manuscripts were lost in this fire. (Yang Jwing-Ming, (2009, December) History of Shaolin Longfist)

Gōnglìquán was already included in the Jingwu curriculum 16 years prior to the Shaolin fire and 17 years prior to the creation of the Guoshu Institute. There is no indication that Shaolin was connected to Jingwu.

The Nanqing Guoshu Institute was created in 1928 by General Zhang Zhiziang. In a biography of her father, Zhang Runsu wrote:

“The defining moment of how Zhang conceived of the plan for the Central Guoshu Institute is explained: while convalescing from an injury in 1926, the newly retired general used martial arts as a form of rehabilitation. During this time, he came to feel that the martial arts would be suitable for the entire Chinese populace.”

Once again we see that the focus of these institutions that heavily influenced modern Chinese martial arts, was anything but combat application, and they continued to propagate toothless tigers for ulterior purposes.

It is important to note that gōnglìquán was not included in the Nanjing Guoshu Institute curriculum as we can see below from Tse’s dissertation where he cites a 1933 recruitment article:

“in the Zhongyangribao 中央日報 on 9 December 1933 shows the numerous styles students were expected to master in three short years for the training programme”

Kicking methods

Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced, Tantui 彈腿Striking courses

(Xingyiquan 形意拳, Tai Chi Chuan 太極拳, Baguaquan 八卦拳, Bajiquan 八極拳, Chaquan 查拳, Xinwushu 新武術, Lianbuquan 練步拳, Zaquan 雜拳, Xingquan 行拳, Chuojiao 戳腳, Pigua 劈掛)Weapons courses

Double-edged sword: (Qingpingjian 青萍劍, Sancaijian 三才劍, Kunwujian 昆吾劍, Longxingjian 龍形劍, Houbeijian 猿臂劍)Single-edge sword: (Meihuadao 梅花刀, Baguadao 八卦刀, Maodao 苗刀, Yingzhandao 應戰刀, Piguadao 劈掛刀)

Pole: (Shaolingun 少林棍, Kunyanggun 群羊棍, Xinwushugun 新武術棍, Tongzigun 童子棍)

Spear: (Duanmenqiang 斷門槍, Daheqiang 大合槍, Suokouqiang 銷口槍)

Whip: (Taishibian 太師鞭)

Competition-based courses

(Sparring, Weapons, Wrestling, Boxing, Bayonet, Pijian 劈劍)Elective courses

(Mianquan zuoluohan 綿拳醉羅漢, Zuibaxian 醉八仙, Zuiquan 醉拳, Houquan 猴拳, Joint locking methods)Special courses

(Qigong 氣功, Tieshashou 鐵砂手, Hongshashou 紅砂手, Swimming, Sprinting, Baseball)Military courses

(Fundamentals of instructing, Combat instructing)

Of note from the figure above, is mention yet again of wrestling but with no specifics or names.

Nanjing Guoshu Institute lasted until 1938 when the Sino-Japanese War (World War II) came to China. Tse writes:

“During the Sino-Japanese War, the Central Guoshu Institute, reduced to a handful of staff members and students, relocated with the Nationalist government to the Chinese interior. Lacking official funding, the Central Guoshu Institute existed in name only until it was disbanded in 1948 on the eve of the Communist takeover.”

Here we see a gap in the transmission of knowledge from the Guoshu Institute in mainland China until the creation of the People’s Republic of China post World War II, and post Chinese Civil War. Given the inclusion of gōnglìquán in styles such as mantis and eagle claw we can see clearly that it was transmitted to these systems directly through Jing Wu.

Decades later we see gōnglìquán coupled with another form straight out of the Guoshu Institute called, lianbuquan (continuous boxing). Lianbuquan is a subject for a separate deep dive. What is important for our study is that the two of these forms show up in modern times under the moniker of Shaolin Longfist, but neither of them are Shaolin, nor Longfist in origin.

Was this related to the Shaolin vs Wudang narrative built by the Guoshu Institute? If so, why would the Guoshu Institute, a government sponsored institution, be inclined to then use Shaolin in its directives or branding, especially after the government burned it down?

SHAOLIN VS WUDANG – A TOXIC CHOICE AT THE GUOSHU INSTITUTE

At the inception of the Guoshu Institute Zhang Zhijiang started a classification of Chinese martial arts systems within the institute that resulted in an immediate and toxic battle that spans decades later into modern times. Tse writes:

“Courses began on 11 May 1928 with an initial intake of 70 to 80 students. Two departments handled the martial arts instruction: wudangmen, shaolinmen. During the early 20th century, Chinese martial arts were typically grouped into styles derived from the Wudang mountains, or from the Shaolin Monastery. The two martial arts sects were diametrically opposed: Wudang focused on internal cultivation, valued softness and was affiliated with Daoism; whereas Shaolin focused external cultivation, valued hardness, and was affiliated with Buddhism. The two departments were headed by two acclaimed masters: the Wudang section by Sun Lutang, and the Shaolin section by Wang Ziping.

It did not take long, however, before internal discord broke out. As the two sects were traditional rivals, the students of either department often clashed with each other in the fledgling institute.”

“The tension between the two departments reached a boiling point, with department heads and the teaching directors facing off against each other to see whether Wudang or Shaolin was superior. With the entire student body watching, Wang Ziping and Gao Zhendong fought fiercely, followed by the teaching directors fighting with bamboo spears. Wang, unhappy with being embroiled in this conflict, eventually resigned and returned to private life in Shanghai.”

This segregation and oversimplification of the rich and varied styles of Chinese boxing and their unique heritage was seared into the minds of those who attended the Guoshu Institute. The Republican Era is one of the most prolific periods for written material on the Chinese martial arts. Thus the impact of those who attended the institute, or were instructors there, who went on to write curriculum and instruction manuals propagated this idea of Shaolin vs Wudang, or Buddhist vs Taoist categorization. The ridiculousness of this is apparent when reading Judkins’ account of Meir Shahar’s book on Shaolin taking notice of Shaolin during the late Ming dynasty, and we find Shaolin at the time incorporating Taoist philosophy and medicine into their practices.

What is amazing to me is how impactful and permanent this became in the Chinese martial arts demographic. After the chaos it caused in the institute, they abolished the classification system by July of the same year, a mere two months after the doors opened.

“By July, the dual-department arrangements were abolished. The Central Guoshu Institute was rearranged into teaching, publishing, and general-affairs divisions.” (Tse)

Of note when permeating the details of the Guoshu Institute, is the fact that later instructors in the institute focused on Western Boxing and Chinese Wrestling for combat methods rather than homegrown martial arts systems. This is important as it shows that all of the other ‘striking’ styles in the institute with Chinese heritage - xingyiquan, taijiquan, baguaquan, bajiquan, chaquan, xinwushu, lianbuquan, zaquan, xingquan, chuojiao, pigua, were not being passed on with combat methods training, only forms training.

This is significant as it proves that by this period in Chinese martial arts history, when it comes to organizations like Jingwu and the Guoshu Institute which were responsible in large part for not only carrying on many of these styles, but elevating their fame and popularity post Chinese Civil War, the fighting application of each style was no longer being transmitted within the halls of these organizations. While it is difficult to ascertain with certainty exactly when such transmission stopped, we can at least see by this point that it is gone. Anyone passing on these systems from this point on, is transmitting empty shells of deceased fighting methods.

A few noteworthy quotes from Tse’s work highlight these points. The first of which is his recounting of the 1928 National Guoshu Examinations (a tournament) where people competed in Chinese weapons demonstrations as well as empty-hand demonstrations. These were non-contact and executed as choreographed routines known as forms or taolu. As we can see from the following quote, Chinese boxing was already dead at the Guoshu Institute:

“Second, of the top 15 examinees, three brothers Zhu Guofu (widely viewed as the winner), Zhu Guozhen, and Zhu Guolu won based on their sparring experience. Well versed in traditional arts (Xingyiquan, Shaolinquan, wrestling and Tai Chi), it was their ‘unofficial’ training in Western boxing which offered them the ability to train against resisting partners while attacking at full intensity with padded gloves.” (Tse, pg 35)

As we can see, when it came to sparring and combat, the participants relied on western boxing rather than their homegrown martial arts styles. The next quote emphasizes the purpose of the institute overall, and why this was acceptable to the government:

“By the late 1930s, the consensus model of physical education best suited for ‘saving the nation through physical exercise’ was a combination of Western military calisthenics, modern sport and guoshu. As such, the Central Sports College’s mandate exactly suited the needs of the times.” (Tse, pg 33)

The negative view of the Chinese boxers after the early 1900’s, plus a desire to modernize and incorporate more western practices to defeat the negative reputation of a weak China on the world stage, there was a gravitation to the western practices that were seen as superior to things beyond just Chinese martial arts. However, the martial arts suffered greatly as the early 20th century was the disintegration of combat application being handed down to the following generations. Much of which was henceforth passed on as empty shells for the next hundred years and more.

Was the labeling of these two sets as Shaolin Longfist even more recent than we think? Could they have been categorized as such after the PRC was born?

To be continued…

REFERENCES

Kennedy, B., & Guo, E. (2010). Jingwu. Blue Snake Books.

Peter Allan Lorge. (2012). Chinese martial arts : from antiquity to the twenty-first century. Cambridge University Press.

Tong Zhongyi. (2005). The Method of Chinese Wrestling. North Atlantic Books.

Reevaluating Jingwu: Would Bruce Lee have existed without it? (2012, August 15). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2012/08/15/reevaluating-jingwu-would-brucle-lee-have-existed-without-it

Cangzhou Martial Arts | 沧州武术 – Taiping Institute. (2024). Taipinginstitute.com. http://taipinginstitute.com/cangzhou-martial-arts

Qi Jiguang (1560/1580). Jixiao Xinshu 紀效新書 New Treatise on Military Efficiency.

Zhu, Jianliang. (2023). A Study on the Evolution of Chinese Wrestling, the Characteristics of the Project and Its Value. Global Sport Science. 1. 10.58195/gss.v1i1.36.

Graceffo, A. (2018). The Wrestler’s Dissertation.

Wikipedia Contributors. (2024, July 16). Changquan. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Changquan

Wikipedia Contributors. (2023, February 22). Taizuquan. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taizuquan#Taizuquan_Changquan

Bringing Northern Styles South: A Brief History of the Liangguang Guoshu Institute. (2018, December 13). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2018/12/13/bringing-northern-styles-south-a-brief-history-of-the-lianguang-guoshu-institute/

The Book Club: The Shaolin Monastery by Meir Shahar, Chapters 5-Conclusion: Unarmed Combat in the Ming and Qing dynasties. (2012, December 7). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2012/12/07/the-book-club-the-shaolin-monastery-by-meir-shahar-chapters-5-conclusion-the-evolution-of-unarmed-martial-arts-in-the-ming-and-qing-dynasties/

Martial Classics: The Complete Fist Canon in Verse. (2018, October 26). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2018/10/25/martial-classics-the-complete-fist-cannon-in-verse/

Tse, A. K. (2019). Unfulfilled Potential: The Central Guoshu Institute in Republican China 1928-1948 [PDF Unfulfilled Potential: The Central Guoshu Institute in Republican China 1928-1948].

Yang, J.-M. (2009, December 30). History of Shaolin Long Fist kung fu. YMAA. https://ymaa.com/articles/history-of-shaolin-long-fist-kung-fu

“Zhongyang guoshuguan she shifanban,” Zhongyang ribao (Nanjing), December 9, 1933.

Lives of Chinese Martial Artists (4): Sun Lutang and the Invention of the “Traditional” Chinese Martial Arts (Part I). (2020, December 17). Kung Fu Tea; Kung Fu Tea. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2020/12/16/lives-of-chinese-martial-artists-4-sun-lutang-and-the-invention-of-the-traditional-chinese-martial-arts-part-i-2/

Secondary References

Yin Honglan. Jindai zhongguo wushu de zhuanxing yanjiu Research on the Transformation of Contemporary Chinese Martial arts]. Shenyang: Dongbei daxue chubanshe, 2016.

Morris, Andrew D. Marrow of the Nation – A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Zhang Runsu, ed. Zhang Zhijiang zhuanlüe [A Short Biography of Zhang Zhijiang]. Shanghai: Xuelin chubanshe, 1994.

Guest Appearance: Mantis Boxing, BJJ, Self-Defense and heresy in martial arts (Ep31 - The Tai Chi Notebook Podcast).

Good Afternoon All, Back here in New England after spending a week at Martial Arts Studies Conference 2024 in Cardiff, UK. The conference was exceptional, but more on that later. For now, I’ll highlight one of the many outstanding encounters of the trip. I had the distinct pleasure this past week of meeting and sitting down with…

Good Afternoon All, Back here in New England after spending a week at the Martial Arts Studies Conference 2024 in Cardiff, UK. The conference was exceptional, but more on that later. For now, I’ll highlight one of the many outstanding encounters of the trip.

I had the distinct pleasure this past week of meeting Graham Barlow of The Tai Chi Notebook Podcast, and Blog. I had seen Graham’s blog a few years ago but never had the honor of meeting him. Graham is a long time practitioner of Chinese martial arts: Tai Chi and Choy Li Fut to name a couple. He then migrated as I did to Brazilian jiu-jitsu where he now spends his time teaching and sharing his passion with others.

Graham and I had tons to talk about, and the dialogue continued when opportunity arose between panels or at the end of the day. Without spoiling it, I’ll now introduce you to one such moment when Graham suddenly pulled out a recorder, and invited me to an impromptu podcast which he pulled off masterfully.

Enjoy the discussion, it goes in my bucket of favorite chats.

Ep31: Mantis Boxing, BJJ, Self-Defense and heresy in martial arts

The Tai Chi Notebook Podcast

For more good stuff from Graham

Find him on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC1SJdsrGOYU45CFU9naMHHg/

Find his website and podcast:

http://www.thetaichinotebook.com/

Facebook:

@TaiChiNotebook