So often in the fighting arts we lack principles or framework to improve our skills through critical analysis. A few artists/fighters/boxers, mainly those willing to take some beatings, are able to improve their skills, while others are left floundering; feeling like they just don’t have what it takes.

When we take our training to the sparring phase, whether on the mat, in the ring, cage, or a backyard, if we find that we are not getting better, that we are simply not improving as fast as we’d like, this manual and the tools enclosed, can make all the difference.

Understand the liabilities and gains, advantages and disadvantages, and the compromise of each position and movement in combat.

Increase your level of skill through easy to understand diagnostics that help you to improve and implement immediate corrective action.

Turn your failures into success.

The 10 Principles

These 10 fighting principles will lay a foundation for us to improve our boxing skills upon. Once we have mastered these we can then explore the offensive side of each principle where relevant to trip up our opponent. Learn the rule. Know the rule. Then we can break the rule.

A note regarding 3 Level Blocking

I recommend training and absorbing the strike blocking course before undertaking these principles as partner training exercises. The blocking system we will use as a method of analyzing, diagnosing, and fixing deficiencies and repairing holes in our game.

Lexicon

Root

Guard

Zone

Door

Rule of Three

Change Levels/Vary Targets

Centerline

Range

Focus

Precision Strike

Emotional Control

An Important Note on Power & Speed (Traits) in the Training Process

When someone walks through the doors of the training hall for the first time, they have two natural traits that can potentially give one fighter an edge over another fighter, but not necessarily decide the victor. However, it is important to note that whenever they become stressed, they will revert to one or both of these traits. It is incumbent upon us, as the more experienced boxers, to teach these initiates to remove these from their natural reactions so they can 1) keep other boxers safe (see concussions, TBI, CTE), and 2) learn new skills. If we train/spar under stress, we will use the traits we walked in the door with, rather than adopting and incorporating the superior skills found in our martial arts training.

Power

Some boxers/opponents are bigger than others. Some are stronger than others even without being bigger. Power is another attribute that can vastly affect the outcome of a fight. If someone hits harder than the person they are fighting, it could mean the expedient end to the encounter without a good defense/fighting strategy. This is important to recognize and why it is key for us as boxers, to improve our body strength through proper training regimens.

Speed

Some boxers are faster than others. He or she who capitalizes on first-strike, can gain a significant advantage in a fight if they know what to do. Someone distracted by the first punch or two, will have trouble defending against the next 3 to 5 punches in a solid combination. If the

first-strike happens to be to the eyes, groin, or throat, this can be over before it begins. Speed can be neutralized by ‘focus’ principle which we’ll cover later in the list.

Remove for Training Purposes

The reason these are a key principle, is that when we train we remove these from our drilling, and only apply them when testing our skills. We keep the speed slow for learning, and fast for testing. This will reduce stress and reliance on natural attributes that can not only un-level the playing field, but mask our own deficiencies by falling back on our inherent abilities instead. These ‘natural’ attributes will be most likely to return during sparring sessions when we are testing our skills. Power is difficult to remove but staying light and learning proper technique will make a stronger fighter even better. We already have the strength, but need to limit it’s expression to keep our training partners safe and coming back for more.

Boxer Principles

#1 - Root

Rooting is an essential part of everything we do when fighting. If we are unbalanced, too upright, and disconnected from the earth, then we will be on the verge of falling over, ineffective in our fighting, and susceptible to throws, trips, and takedowns.

How to Root

Lengthen your stance and drop your pelvis closer to the ground by bending the knees. This will assist in stability and not falling down or being rocked when blocking, striking, or being pushed/pressed.

Everything comes with a price in fighting. In order to gain one advantage, we must give up another.

It’s the nature of the beast. There are three heights we can use in your stances:

High - fast, mobile, used more for out of range, pre-engagement.

Mid - medium speed, semi-mobile, used for striking, kicking range.

Low - low speed, decreased mobility, used for close range striking such as elbows,

knees, and grappling/clinchwork.

Each of these has it’s pros and cons.

High Stance - 3 Dimensional Stance (weight 40% front leg, 60% rear)

A high stance does not mean we have to sacrifice our rooting. If we bend our knees slightly and drop our weight. Keep our body weight on the balls of our feet for maximum stability/mobility. This stance should be used when we are trying to A) get in and out quickly on an opponent. B) are still outside ‘critical distance’ (see Range Principle). C) in need of an escape with faster footwork to get away from our opponent and create space.

Mid Stance - 3 Dimensional Stance (weight 40% front leg, 60% rear)

A mid level stance is the best of both worlds. We have a bit more stability without completely compromising mobility. We cannot move as quickly as in a high stance, but we are fairly functional and well rooted for striking and kicking. This is a good stance to use once we have passed inside ‘critical distance’ (see Range), or are in mid range and engaged in striking.

Low Stance - Monkey Stance (weight 60% front leg, 40% rear)

Low stances are great for digging in and being battle-ready for in-the-pocket fighting. Once we have moved into close range, we drop our stance for the best stability. Mobility is severely decreased here but once we are in grappling range we are extremely vulnerable to throws, shoots, and takedowns, so a lower entrenched stance is a must!

Balls of the feet

Keep the weight centered on the front ball, or pad of the foot. Flat footed means we can’t move quickly. <HINT>Catching an opponent flat footed is a good opportunity for an offensive attack. The heel should still touch in most cases, but light on the ground. Keep the weight off the toes as they are meant to balance, stabilize, and propel, not support our weight full time.

#2 - Guard

Guard principle defines a proper defensive positioning of our hands and arms. A quality guard position reduces the number of available targets that we present to an opponent. When used correctly, it also protects us while we are striking by closing doors and limiting the counter-strike potential of our opponent.One In/One Out is the phrase to remember. During striking or blocking we move our other hand back to a defensive position (one hand goes out, one hand comes in). If we extend two arms simultaneously (two out), we expose targets, lose strength and reflex, and we will be unable to block the opponent's counter-strike.

The Guard Defined

With our body in a bladed position (see blading under #8 Centerline Principle), our hands naturally stagger one in front of the other. This allows for us to gain range on the opponent with our lead hand making it easier to reach them with our initial strike. We also protect our centerline from attacks to some of the precision strike targets that would otherwise be left open if we faced off with our opponent in a squared up position (torso perpendicular to our opponent).It is important in the guard position to keep the elbows tight, or forearms vertical. Do not let the elbows wing outwards; they protect the ribs and maximize the strength of the arms. Be sure that you are not cocking your wrists in this position as this will mask incorrect forearm alignment and slow the arms down, debilitating our blocking methods.

Hands on shoulders

When faced off with our opponent in a neutral position, we line our hands up with the opponent's shoulders. If our hands are too close together, we open up targets on the outside lines where we are anatomically weak. If our hands are too far apart, it will be difficult to block strikes to the center and our delayed response will cause us to get hit down the middle. Shoulder width is a good spot. This creates a perceived opening down the center, feeding their strikes where we are strong. Remember that the hand alignment is as if looking over your shoulder, not your eye to their shoulder.

Hand Height

The height of the hands is determined by A) our height in relation to the the height of the opponent, B) the range to the opponent, and C) where we can comfortably keep them so they can react quickly against incoming blows. The hands should be held up to roughly jaw/cheek level with fingers relaxed but straight; not closed fists as this tenses the arms and delays reaction time for blocking. Failure to hold the hands up high enough while in striking range, will prevent us from blocking head strikes effectively. If our hands are held up too high (say eye level or higher), we will not only expose body targets, but weaken our arms as they become quickly fatigued. This will cause a delay in response time and lead to failed blocks.NOTE: we can always compliment your blocks with slipping and ducking later on, but it is good to hone our blocks to the highest degree possible so that we know they are dependable and we can trust them when they are needed.

Guard Hand

Guard hand is the hand that returns to defend while the other hand is striking. The effective use of the ‘guard hand’ while striking can maximize our defense while taking an offensive action. Be sure to return the non-striking hand to the guard position while your other arm is extended during a strike. This is critical to shutting down counter-strikes.

Connecting Principles: Zone, Door, Range

#3 - Zone

To enhance our offense and defense while striking, and blocking we use zones to demarcate where we should and should not be placing our arms.

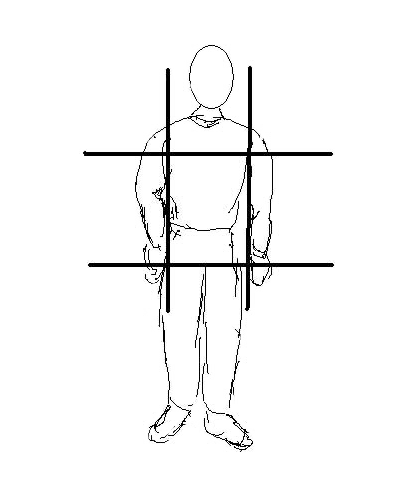

The 9 zones

The body is divided into 9 sections (see diagram 1) called zones. These zones help define a system of where our hand should and should not be while fighting. Zone principle can be divided into offensive and defensive categories. Practitioners should focus on learning the defensive side first, and later adding the offensive.

Defending

In order to effectively defend as many doors (potential openings for opponents to hit us - see 'Door' principle) as possible, our hands should not pass between more than 2 zones. To put this in practice when blocking, our left hand is responsible for our left side of center. Our right hand is responsible for covering the right of center. Never cross more than 2 zones.

Example: Right hand is in the top left quadrant in diagram 1. Opponent throws a round kick at the right leg (lower right quadrant). Our right hand would have to cross 2 zones to get there and is therefore out of position, and unable to return to the top left quadrant to defend the open door (our head) which is now accessible to our opponents strike.

Takeaway - never block leg kick with the hand. This exposes the head for the follow-up.

Groin Attacks

The line of divide for the lower quadrants is right below the groin. This allows for us to still use the hand to defend this target when it is attacked. However, given we are still dropping the hand, it is imperative to have the guard hand defending up above, and to retract our hand expediently after a successful block.

#4 - Door

A door is an opening we traverse through. In fighting, this is an opening to an effective strike target. ‘Door' is the principle of keeping as many doors closed as possible while fighting. Doors are openings for strikes and kicks to walk through. This principle is heavily connected to Guard Principle as well as Precision Strike. It is recommended to review both of these principles to better understand how this works.

A proper guard will close down many open doors eliminating the opportunity for the opponent to strike a vital target and land a knockout blow, or rib break.

Keys to Success

Elbows In - keeping the elbows in allows for the ribs to stay protected and the upper block to function with proper strength.

Hands in line with shoulders - this forces the opponent to go around, or inside, our arms in order to hit us. Also assists the upper block in having the strength to function properly.

Open Doors - when striking we naturally open doors. To minimize the potential negative effects of this we must be sure to apply zone, guard, blading (see centerline) in conjunction to limit our open doors.

Neutral Position

Neutral position is where we want to work from early on against an opponent. This is when we are aligned perfectly with our opponent. Our feet are lined up with their feet. When they circle we match the opposite direction to come back to neutral. When we have a bladed stance (see centerline) and move to match their stance, we neutralize advantages they may gain from angles. This increases the effectiveness of our blocking system, and shuts down access to certain vulnerable targets.

To put this in context with real numbers, let’s apply the following:

Assume that our blocking is proficient to a base level, and we are blocking 80-90% of the shots our opponent takes on us when they are directly in front in the neutral position. If they move one inch to the left or right, our effective block rate would drop to 30% or less. Later on we introduce a principle known as angles and trajectory. This is how we can disassemble someone’s guard, but it is a high level principle encountered with proficient boxers.

#5 - Rule of Three

The rule of three states that the first two strikes we throw can be effectively neutralized by even an unskilled opponent. We have two arms, and our opponent has two arms. We punch with two arms, they can block with two arms. However, a less-skilled opponent will not return their blocking hand to the correct guard position and will thus have created a hole in their defense, i.e. what we try to encourage for ourselves with proper use of guard, door, zone, and centerline principles.

Combos

This is why strike combinations, a.k.a., combos, are imperative to our success when striking. On our third strike or higher in a combo, we have a higher probability to penetrate the opponents guard, and successfully land a strike.

When training striking, we practice combinations containing at least three strikes in the air, or on a heavy bag to make this not only habitual, but integrated with our defensive principles at the same time.

There are many combinations that can be thrown with just three strikes. Start there, and work yourself up to a higher number as you grow comfortable. The objective is to throw 5, 7, or 9 strikes with our hands going back home to our guard position between each strike.

Why go higher than three?

A higher skilled opponent will be able to block more than three strikes in a row. Over time, our objective is to string more and more punches together so that eventually our opponent will make a mistake and be out of position. Breaking down their guard. At which point we can capitalize on the open door we created in their defense. The more skill the opponent has, the higher the number of strikes needed to open doors without the use of more advanced tactics such as fakes, feints, hidden motion, etc.

However, the converse also applies to the aggressor; the more punches we string together, the more likely we are to fail to guard correctly. Thus creating openings in our own defense.

(see number 8 Centerline for more information on Rule of Three)

#6 - Change Levels/Vary Targets

Changing levels refers to varying the targets of our punches between the head, body, groin, and legs, to avoid predictability and confuse the opponent’s defenses.

The low-skilled boxer will typically focus on the head for psychological reasons, and because it takes a little more practice to locate effective targets on the body. Although the skull is rather impermeable to strikes over a large portion of it’s surface area.

Head-hunting, or head-focused striking, is easier for an opponent to block with their hands up, and far easier for taller opponents to defend against shorter aggressors. When we focus solely on the head, our opponent knows where the punches are going and has little distance to travel in order to block. They can simply put their hands up in a defensive posture and be moderately effective versus a low-skilled striker.

However, the less-skilled fighter will not be able to block shots to the body in an effective manner. Even if they do block the lower shots, they will probably not return to the correct guard position and will be open for a headshot.

By intermixing high and low shots during combinations, the opponent is forced to move their defense up and down with different blocks, increasing the difficulty of the defense and increasing the likelihood they will violate 'zone principle’, ‘guard principle’, and 'door principle'. This type of variation is what leads to holes, or open doors in the opponent’s defense, and is the foundation for the ‘precision strike’ principle seen below.

Vary Targets

Vary targets is used in conjunction with 'Rule of Three' and 'Changing Levels' to confuse our opponent and lure them out of position with their blocking arms, thus opening doors. When applying this, use combinations that change not only from high to low, low to high but outside to inside, inside to outside. Repeatedly attacking the same target makes it easy for an opponent to defend.

#7 - Centerline

Centerline Principle is protecting our centerline by blading and circling so we do not end up square to our opponent.

Square

The body is turned perpendicular facing toward the opponent (think feet side by side) giving each arm equal striking range and strength. Vulnerabilities include increased access to precision strike targets, to include groin, and indefensible centerline, and allows the opponent to use ‘Three Up the Middle’ (see below).

Blading

Our body is turned to a 45 degree angle (shoulders and hips) to deflect punches from vital targets, facilitate a ‘1 in and 1 out’ with our arms, to help with rooting and balance, and slim down our profile thereby creating a smaller target. Deficiencies with this stance - decreased power with the lead hand, unequal access with rear hand.

Three Up the Middle

Capitalizing on an opponent's bad position and lack of blading. When an opponent is square to us and their arms are up, we fire a 3 punch combination up the middle changing levels. This will almost guarantee a hit with at least one, if not all three strikes.

#8 - Range

Range, and our ability to reconnoiter, and maneuver through it, is absolutely crucial in fighting. Range means the difference in getting hit or not hit, in getting kicked, or trying to strike when we should be kicking. Our blocks working properly, or knowing when we should change gears to elbow and knee strikes, grappling, or clinchwork. Paying attention to, and learning range intimately, can make you a highly effective mantis boxer both offensively, and defensively.

Critical Distance

The line that separates us from being hit or not being hit by our opponent. Critical Distance is determined by the range just outside the reach of our opponents longest weapon - their rear leg kick.

3 Ranges

Long Range - this is the range outside critical distance or right on the edge of it. It is where there is no fight, or the very beginnings of a fight. The range where we use a bridging tactic to enter, and we learn to be acutely aware of when we cross over, or our opponent advances inside of our range.

Mid Range - the range that fight really takes place. Kicks, strikes, some knee techniques, or shoots for takedowns are all open game here. While some grabbing and seizing will take place at this range it is really the initiation of that phase and not standard practice to grab and seize from here unless catching a kick. A fatal flaw at this range, is actually grabbing, or attempting a clinch, without advancing to close range.

Close Range - this is the stand-up grappling range. This is where our meat and potatoes lie when it comes to throws and locks. Close range is extremely important in a fight. Even a novice boxer will charge to this range to protect themselves from getting hit. It is imperative that our skillset include methods to dominate this region. In this range, we also need to change our blocks, and drop our stance to have a good shoot defense. Knowing the clinches, hooks and grips and how to defend against them is imperative to success. Throws, trips, and takedowns are in play. Elbows and knees are primary weapons and punching/palms become secondary. Most kicks are obsolete in this range.

Bridging

This phase of combat is is an artform in and of itself (see Bridging: How to Close Distance in a Fight`). Musashi, one of the great samurai and author of ‘A Book of 5 Rings’, was a master at this tactic with a sword. This single act, can completely define the outcome of a battle.

When we pass critical distance on the offense, our opponent has the advantage. While we are focused on moving in and striking, or attempting a takedown, they are waiting and watching for an opening to counter-strike, or stuff our takedown. This is especially true if they have acquired the focus principle we will discuss below.

As you will see in the article on bridging, there are layers of complexity with the bridge. The simplest solution early on, is to always strike when moving in. Later we will learn more in-depth bridging tactics (double kick, flying knee, superman punch, fakes, feints, etc.).

For now, focus on using your long range weapons (kicks) when closing distance, or striking when stepping or shuffling in. If you are already inside ‘Critical Distance’ and you aren’t striking, grappling, kicking, clinching, throwing, then you are in trouble and rough seas lie ahead.

More on Range

#9 - Focus

Focus Principle is how we neutralize our opponent's speed so we are able to block their punches in time. When our opponent is within striking range we are reacting to their action, so we are always behind. Focus principle allows us to catch up.

Using our peripheral vision to counter our opponent's speed while maximizing our reflex time for blocking is what focus principle comes down to. By all accounts we seem almost superhuman after we learn to do this. When we stare at a punch coming at our face, and then try to block it, we will fail every time and get hit in the face. If we are looking off-line, and seeing the punch with our peripheral vision however, we will now have the reaction time to block it.

This is due to the way our eyes function with different parts of the brain. In simplest terms - our acute vision is tied to the conscious brain; where we analyze and process data coming through the eyes. Peripheral vision is connected with the subconscious, and reacts to external stimuli without the brain needing to give it permission first.

Maintaining focus principle while fighting is difficult and requires diligent practice. We must attempt to stay in focus principle when on the defensive, ignoring the motion of the opponent which can pull our eyes back to acute focus. Subsequently, getting back to peripheral vision after getting hit is an even more difficult task, as the brain wants to analyze what just happened, and the ego wants to discuss it with a therapist. We must drown out all these other stimuli and revert back to peripheral vision as quickly as possible to give us the greatest chance of blocking the next attack that is guaranteed to be inbound. To do this, we cross and uncross our eyes quickly to get back into focus, or rather, out of focus. The method I prefer, is opening the eyes as wide as possible and letting them reset.

#10 - Precision Strike

Precision Strike, is the principle of striking to vital targets, or targets that have more destructive impact than other areas of the body. This is a common concept in many styles of martial arts but is often conflated with mysticism, superpowers, or charlatanism.

Below are the actual ‘soft targets’ we all have on our body, and the desired effect of striking someone there. For more information you may want to read ‘Xiao Da: The Truth on Effective Strike’

Head Targets

Throat - Crush the larynx making it difficult to impossible for opponent to breathe

Side of Neck (Brachial Stun) - Knock out blow, or excrutiating pain at the least

Back of Neck (Occipital Lobe) - Knock out blow

Jaw - Break or Dislocation. Extreme pain.

Nose - Pain. Bleeding. Watery Eyes causing reduced vision.

Eyes - Loss of sight. Extreme pain.

Ears - Tear them off for extreme pain.

Temple - Knock out blow. Extreme pain. Disorientation.

Body Targets

Shin - Extreme pain and discomfort.

Knee - Break/Dislocation. Extreme pain. Loss of Mobility.

Outer Thigh - A solid kick to this target can cripple a fighter and make them think twice about closing distance.

Inner Thigh (Femoral Nerve) - Identical to the Outer Thigh, this target causes excruciating pain.

Groin - Extreme pain and discomfort. Potentially cripple opponent.

Bladder - Pain and discomfort. Possible bladder release. (you figure it out)

Rib - Break. Extreme pain and discomfort. Possible breathing effects.

Kidney - Potential knock out as well as extreme pain.

Liver - Knock out blow. Extreme pain/discomfort.

Stomach - Knock out blow. Extreme pain/discomfort.

Solar Plexus - High concentration of nerves. Also the meeting point of the heart, liver.

Collar Bone - Break. Extreme pain. Loss of use of arm on that side. Harder target to hit and not effective on everyone.

Emotional Control

As a final point, one of our goals in training is to develop ‘Emotional Control’. I wrote extensively on this in an article on this subject, shot a video, and recorded a podcast. Yes, it is that important!!!

The following link should explain everything you need to know about how and why this piece is arguably the most impactful to our martial arts, and life.