A Daemon in my Dojo

The afternoon sun turns to shadow early as the solar cycle wanes and we fast approach the winter solstice. I was finishing my training and sitting down to meditate when the visitor walked in.

A new visitor arrived in my dōjō today, a stranger from a far off land. It is the beginning of autumn in the year 2012. Dōjō, or ‘way place’ in Japanese, a place to study the way of ‘something’, typically martial arts. In Chinese martial arts we call it a wǔ guǎn (wǔshù guǎn), or martial hall, the place in which we gather for the study martial arts.

The afternoon sun turns to shadow early as the solar cycle wanes, and we fast approach the winter solstice. I was finishing my training and sitting down to meditate when the visitor walked in. Lately I have been consistently practicing meditation as a post training routine to clear the mind, to take inventory, and to stay grateful.

It has been thirteen years since I began practicing Praying Mantis Boxing (tángláng quán), and a bit over a year since undertaking the art of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (B.J.J.). I recently competed in my first BJJ competition as a newish white belt. Currently, I am training and coaching six days per week, as has been the case for the past eight years. When I’m not teaching or occasionally unfurling my wings to deftly dance off a cliff to reach for the clouds above, I pen articles on martial arts as thoughts and ideas materialize that may be of use for others on this path. I have been cross training in other arts for a few years, nothing serious prior to BJJ, but enough so that I have been experiencing modalities outside of Chinese boxing arts; seeing a broader picture.

I sit regulating my breathing, trying to focus my mind. A bright warm light washes over me as the door opens. The stranger interrupts with abrupt words that leap forth like a flash of briny sea water surging to shore on the rush of high tide. These noises flood my brain. At first I am annoyed at this intrusion, and try to ignore it for a moment of solitude. Then, I pause to listen to what he said to me.

As my mind churns over the information it feels as if this visitor is casting a bright spotlight into the deepest umbra in my brain. He begins to spout emphatically about Bēng Bù, crushing step for short, but the longer meaning is – steps to cause the enemy to collapse and fall into ruin. Bēng bù is a shadow boxing set found in styles of mantis boxing, I have been practicing this set since 2005 learning five or more versions from the various lines of mantis boxing, part of my quest to decipher the true intent behind the shadow boxing shell transmitted through mantis boxing lineages for the past one hundred years, or more. I’ve vigorously searched for the hand-to-hand combat applications originally intended by the creator(s), wanting my own continuation of this boxing style to be effective in fighting. Something I have rarely seen thus far.

Eventually I settled onto one version of bēng bù that I train a few times per week, occasionally spending time mulling over the potential applications within my head. The stranger's words snap like a bolt of lightning crackling through my mind. Riding along the spectrum of light his question crackles forth: “Why is bēng bù, like so many other Mantis Boxing forms, begun with and finished with the move, ‘Mantis Catches Cicada’?”, he continues on, “This is not a finishing move to end a fight, so why would this technique of all of them be laid out in form after form almost as bookends?”, “Is this just stylization? Is it a meaningful application?” His questions intrigue my mind, I begin chasing the lightning along its incongruous path.

Code breaking comes to mind, more specifically ciphers. I reply to the stranger, “A cipher used to crack open an ancient codex. A boxing form, in this case crushing step, a set of choreographed moves from a boxer of old, is this the codex and Mantis Catches Cicada the cipher? Perhaps this move is ‘the key’ to unlock the applications within the form?” I begin traversing the halls of the labyrinth in my mind, searching every corner, opening every door, looking at each move in bēng bù from a ‘two hooks’ (neck and arm, or colloquially known in fighting circles as a ‘clinch’ position.

The dialogue and the air around this impromptu visitor, ripple with electricity in the air. I struggle to keep pace with the trove of possibilities his questions raise. As I peruse the catalog of choreography in each road of the set, I conclude that some of the bēng bù boxing moves could certainly function from this position, but others clearly not. The questions then enter my mind, “Where is he from?”, “What, or who, is the source of visitors knowledge?”, “How did he happen upon my dojo?”. I asked his name. “Wang”, he replied.

Wang was a pesty guest, talking incessantly his entire visit. “Does he ever shut up?”, I wondered to myself silently. A wave of empathy washed over me, he did travel from afar, and spent so much time alone unable to talk to anyone about this subject matter. A topic that must be yearning to escape the prison of his mind.

Wang spoke day and night, following me home after classes. He had nowhere else to stay on his visit, I felt compelled to open my home to him, annoyed at times, but grateful for his illuminating thoughts and inquiries.

During his stay I rarely caught a wink of sleep. Wang sat next to my bed at night incessantly rambling till the sun came up. With no choice I lay awake listening to the chatter, staring at the ceiling, throwing off the sheets in exasperation, pacing the room, and spending nights shadow boxing while Wang rolled on. I caught a wink of shuteye here and there, only to rise early again the next day. A true insomniac, Wang did not sleep, obsessed with his ideas which spawned forth like seven hundred baby mantids hatching from an ootheca in the midsummer garden.

With seemingly nowhere else to be, Wang stayed for weeks, revealing a series of mantis boxing positions and hand-to-hand combat applications I had never considered before. I immediately went to task testing these in drills, sparring, and grappling as Wang sat looking on in satisfaction. A new world arose around me; a schism manifested, a cataclysmic shift in my worldview of fighting.

Wang, seeing my progress, bid me farewell for the time being, proclaiming as he exited my dojo, “Perhaps I’ll return, but for now, you need to chew for a while before we can dine again.” I bowed to Wang in gratitude, and wished him well on his travels. Thus concluded my first visit with the daemon who sojourned to my dojo.

Discovering the 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing

The above short story is an allegory based on real events. An episode in my life back in 2012 consiting of an explosion of ideas and thoughts. The dōjō is not the one I train and coach inside night after night, but rather the one I spend far more time in, the one inside my mind.

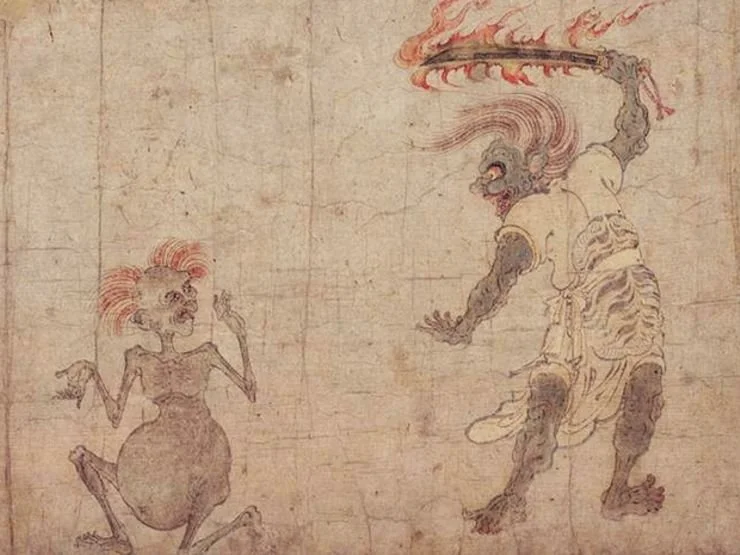

My daemon, Wang, is based on Wang Lang the mythical founder of mantis boxing. The man accredited with the origin of this boxing style hundreds, or thousands of years ago, depending on who you listen to. You can read more about Wang Lang in an article I wrote on his possible accreditation to the art here: The Apotheosis of Wang Lang

Prior to this experience I had little in the way of instruction or conversance with the 12 keywords of Mantis Boxing. I certainly knew of them, as most serious and long term practitioners of the art do, but I had yet to delve into them. From my observations and experiences any information regarding these keywords, and conversations surrounding them amongst mantis boxers and coaches, devolved into arguments over what the ‘correct’ keywords are, and their true meaning.

The thoughts I had on ‘mantis catches cicada’ were real. However, while this was a ground-breaking revelation that sparked an age of discovery, and helped lead me onto a fruitful path, years later I debunked this theory when my research exposed mantis catches cicada as nothing more than a — brand moniker, rather than an actual fighting technique. A mantis boxing en garde to proclaim, ‘We do mantis.’ This moment in time though, when all these thoughts began to appear, shifted my brain into thinking of each move from a whole new pillar of fighting — wrestling/grappling.

My daemon helped me to see the first three of the twelve keywords of mantis boxing with new eyes. I began to commit pen to paper, to record these thoughts as they manifested. It crawled from my pores with an unstoppable force. We took photos. I wrote my first quasi-article on ‘What is Praying Mantis Boxing’, now titled The Heart of the Mantis, a rough experience. This idea that wrestling was an integral part of mantis boxing was scoffed at by the mantis boxing community, and some were extremely rude in their rebuttals. I charged forth anyway, fully committed and stalwart in my belief that I was on the right path. As with any new endeavor, I was getting my legs under me as I awoke from a slumber.

Over the ensuing years Wang would come by for a visit from time to time. If I was not paying attention he would splash hot tea on my brain, burning me so I would once more bring my full attention to bear on what he had to say. As I continued boxing, grappling, and progressing in BJJ I unlocked more and more positions and fighting applications. An increasing number of the keywords unlocked before my eyes.

I noticed a similarity with other grappling arts and recalled Gichin Funakoshi remarking in his book Karate-Do that I read back in 1999, that Kara-Te (way of the Tang Hand) was a blend of techniques Okinawan nobles would bring home from southern China during the Tang dynasty, and blend them with their indigenous fighting arts. Years later finding out those indigenous arts were wrestling.

As we sat in the garden sipping tea on one of Wang’s visits, he asked me: “What were China’s indigenous fighting arts?” I began to delve into the history of the Chinese martial arts ecosystem as a whole, coming across...Bokh, the Mongolian wrestling arts still alive to this day. This was enlightening especially since many techniques looked similar to postures found within Mantis Boxing (and other styles) forms of Chinese martial arts that I had studied over the years, to include: taijiquan, eagle claw, long fist, and more.

Bokh, and its history/influence on Chinese culture when the Mongols invaded and took over China during the Yuan dynasty, made me grossly aware that Mantis Boxing along with other Northern Chinese Martial Arts styles that I had studied over the years, contained a great deal of stand-up grappling, or wrestling. This realization has evolved over time as my understanding has grown, now aware that the Manchu were heavily vested in wrestling culture, ruling China for over 250 years during the Qing dynasty; the last of the dynastic eras of China. From there a growing realization of Han wrestling, jacket and no jacket wrestling from the Shaanxi, Shanxi provinces, along with a broader understanding of how much wrestling was part and parcel to so many cultures the world over, almost integral to our DNA as a species.

I could now see that a bulk of these ‘systems’ from northern China seemed to revolve ‘around’ grappling as a primary pillar, using methods and tools to facilitate ways to clinch and grapple an opponent, to throw or trip them to the ground.

The other primary art I trained and taught at the time of writing the above essay, was Taijiquan, specifically Yang family style which was originally known as small cotton boxing. The principles within that style also screamed grappling and I began to dig into the 13 keywords of Taijiquan, performing a comparative analysis of mantis boxing and supreme ultimate boxing after finding so many parallels. This is a working document that I return to from time to time over the years - Brothers in Arms: Mantis Boxing versus Supreme Ultimate Boxing

Arriving at ‘my’ 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing

Hook, Clinch, and Pluck were the first lessons from Wang Lang. These were followed by Lean. Lean was particularly elusive at first simply because myself being a striker/kicker I failed to see why we would want to lean in a fight, only to give our opponent a shorter distance to hit us in the head. Once applied to grappling and the close distance fight, leaning becomes integral to our survival.

The other keywords were increasingly harder to unravel, with growing absences between visits from my daemon. Long arduous periods of contemplation and frustration, times where I would continue to ask questions into an endless vacant void. From time to time though, my daemon would once more return, once more shredding the thick overgrown vegetation of confusion with razor sharp claws.

Once I could see through the adeptly graven undergrowth, and light shine upon the darkness once more, new techniques would reveal themselves. Eventually, a keyword, or two, would whisper from the lips of my daemon and wisp through the tattered leaves in the garden.

Adhere was the next to become apparent, especially due to its significance in BJJ, where controlling, or consuming space from an enemy while grappling on the ground was so significant. The same was true in stand-up grappling.

Strike was not as simple as it seemed. Ultimately, it is simple ‘to hit’, but why would something so obvious be a keyword? My daemon laughed at me, “If you don’t strike as you Enter, you’ll meet your doom.” he said. “If you do not strike to Connect, you will fail to find your enemies limbs, and meet their fists as you arrive.” “If you do not strike in the clinch, be prepared to receive…injury!”, he laughed harder.

Connect & Stick were the next keywords to be codified. Wang Lang, ever the sarcastic ethereal daemon, made disgusting references to gum, saliva, and the various stages of sticking, to bring these epiphanies to life. “That’s the easy part, but knowing when and how to use them without being punished is another issue entirely.” Offensive application versus defensive utilization was worthy of deep study, otherwise a broken nose would ensue.

Beng, to collapse and Fall Into Ruin came to me in the garden one day. Wang Lang was hanging out on the branches of my kale plants attempting to capture unsuspecting wasps, butterflies, and bees. As his hook snapped out to strike an unsuspecting passerby, he did not crush this victim with his deft strike, but caused it to collapse and fold in upon itself, crumbling to the ground below.

Beng was such a loud lesson that I had to write an article for it and publish it in a magazine for all to see. The idea that causing the opponent to collapse and fall into ruin using various methods, was revelatory to say the least. Especially since one of the core forms of mantis uses this in its name.

Wicked, or in other words, to be ‘sly, deceitful, or tricky’. Wang Lang just flat out hit me over the head with a heavenly strike on this one. What is a fake, or feint when boxing, if not a ruse to open up the opponent and land a strike? A loud noise, bang, or yell - are they not a diversion to enrapture our opponent for a brief moment so that we may gain unfettered access to enter and annihilate them? The use of pluck to force an opponent in the opposing direction of our throw, trip, or takedown, gain freedom to adhere and lean as we barrel forth into a takedown; is that not beguiling?

Wang Lang was rather condescending on that last one, especially since I had been using these tools for years yet failed to see the connection to the keyword he left etched in history.

Hang was another slap on the head, or ‘duh’ moment. Hang was pointed out by my daemon genius spirit. He vaingloriously proclaimed to me - “If you don’t root, lower, ‘hang’ on your adversary when engaged with hooks in the clinch, you’ll get tossed and trampled like you tried to wrestle an elephant!!!”

The Keys to the Style? Or Keys to the Stylist?

The 12 keyword formula of Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳) houses the principles that help define the art. These characters, or variations of them, have been passed down through the common vernacular of Chinese boxing methods in northern China. While not unique to mantis boxing, and evidence of their existence in other styles of the region and time period exist, they can establish a definitive strategy for mantis boxers; much more so than a collection of tao lu (forms) that have no consistency from one branch of the style to the next.

Replication of these keywords does exist among the various lineages of mantis boxing, especially in the first few keywords. No matter the style, many of the more obvious in name keywords such as: Strike, Crush, Hook, Enter, Lean, Clinch, Pluck can be witnessed in Mantis Boxing forms. Those which are harder to mimic in the air - Connect, Stick, Adhere, Hang, and Wicked, are absent in the forms from all indications, and are found rather through live training and sparring practice.

Many of the grappling specific keywords exist in various forms of martial arts still alive today. Although lost within Mantis Boxing lines, one needs simply look at other unarmed combative styles to find evidence of not only their existence, but also significance when it comes to fighting.

An art, of any type, is not defined by hard and fast rules, but is open to interpretation and adaptation by the artist. Keywords of a style, or system of boxing, are a series of principles to guide the practitioner. The definition of these principles and what they mean is highly variable and intimately related to the boxer using and/or coaching them.

The keywords can change from boxer to boxer, allowing for wide adaptation and freedom of expression, and each boxer can select which they rely on more than others. As long as the boxer adheres to a loose framework which includes the hook and pluck keywords, as well as the connecting and sticking specifically, then the stylist is still manifesting an art which mimics the fighting traits of the praying mantis.

These 12 keywords I pass on represent the foundational core of my mantis boxing art. Which strikes, kicks, throws, trips, submissions, you choose to use when you fight can vary widely from my own. And yet, with common principles we bond together as martial artists, share, and reward one another’s successes.

It took me six years to unlock what these keywords mean to me. Use them to discover your own methods. Keep what is valuable to you, discard what is not. Practice with it, fight with it, and your own truth will be one day be revealed to you. Validity in martial arts is not established by the opinion of others, but rather it is, and should be, measured by the success of the actions and execution of our methods.

To learn more about my 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing you can find a course I have available that combines video instruction with more detail in written explanations and descriptions of each of the 12 keywords.

The Art of Counter-Striking

There are two types of fighters - offensive fighters, and counter-fighters. A list of descriptors for offensive fighters is comprised of - aggressive, confrontational, type-A personality, control freaks, etc. On the inverse, the counter-fighter may be described as - laid back, docile, relaxed, non-confrontational. I contest that, no matter what your style of fighting is, I will make the case that the counter-striking skills are crucial to both camps of fighters. For now, if you are an offensive fighter, skip ahead to the section below on Offensive Fighters. If you are a Counter-Fighter, then carry on to the next paragraph.

photo by Max Kotchouro

There are two types of fighters - offensive fighters, and counter-fighters. A list of descriptors that may indicate we are an offensive style fighter are comprised of, but not limited to - competitive, aggressive, confrontational, type-A personality, control freak. We know who we are! On the inverse, if we’re a counter-fighter, we may be described as - laid back, docile, relaxed, non-confrontational. I contest that, no matter what our style of fighting is, counter-striking skills are crucial to both camps of fighters. For now, if you are an offensive fighter, skip ahead to the section below on offensive fighters. If you are a counter-fighter, then continue on to the next paragraph.

Counter-Fighters

If we are a counter-fighter, then the following techniques are going to be our bread and butter. We are the ‘shield-bearers’, the ‘defenders’. After we attain a base proficiency in blocking then we will need to immediately gravitate towards applying counter-strikes. We cannot defend, or retreat forever. In order to prevent our aggressor from becoming emboldened and running us down, we need to hit them back from time to time to send a message.

What defines “a base proficiency in blocking?” This manifests from learning to trust our blocks; an absolutely crucial facet to counter-striking strategy. Slipping and ducking can apply here as well. When we’re new to the striking arts we learn to block, slip, duck, dodge, but in the interim we usually have one, and only one gear we know how to use in regards to our footwork - reverse. This is OK at first, as it hedges our bets on blocking and keeps us at a safer distance. Meaning we can block, but we’re essentially neutralizing our opponents attack with our footwork at the same time.

If we examine this move for move, our opponent advances with a strike and our footwork, ‘could’, if properly timed and spaced, eliminate the need to block. While this is a fair tactic, we cannot backup forever and our opponent can move forward further and faster than we can move backwards.

The solution comes down to taming our fear, or attaining some semblance of emotional control. We do this by either learning to take a punch (an ill advised solution), or by gaining proficiency in blocking, slipping, ducking, or a combination thereof. The latter cogent so that our defensive deflection is dependable and worthy of trust. Once we have achieved this skill, then we can venture forth into the counter techniques shown further below. First, we need to address those offensive fighters, whose skills are also necessary to us when faced off against another counter-fighter. Otherwise…there is just an uncomfortable stare down.

Offensive Fighters

If we’re an offensive fighter then our strategy/tactics/game are comprised of - going in, stealing the initiative; or obtaining the first-strike. Unsettling our opponent so they cannot gain first-strike capability on us. We prefer to dictate the pace and energy of the fight. For us, bridging tactics, rather than counter-striking are the key to our survival; the primary swords in our arsenal. In a battlefield scenario, we are the ‘cavalry’, or the ‘archers’. We launch the preliminary attack, engaging the enemy, gaining initiative, and disrupting their defense.

Let’s examine this more closely in a play by play:

We launch our first-strike attack on our opponent.

As we enter the fray they blast us in the leg with a powerful round kick to the soft tissue of the quadricep muscle (think charly horse). Or equally destructive, the femoral nerve on the inside of the thigh.

This counter-attack stops us in our tracks and we miss our attack opportunity, opting to retreat and recover our position instead of pressing forth.

The second attempt…ends with the same result. If our opponent is good, then they nailed us in the same target as the first time.

We may muster the courage to try once more with the same assault. For the sake of this scenario, we meet the same fate for the third time. Our leg is now feeling like rubber and we decide at this point to stop pressing the attack and try to nurse our wounds.

What’s next? Scroll back up to the section on counter-fighting because we just got schooled on why, as offensive fighters, we need to have a counter-striking game in our arsenal. Our opponent just turned us into a counter-fighter.

Counter-Strike Setups

In order to develop counter-striking as an intrinsic part of our game, there are some simple counters we can start with. From there we can increase the complexity. Let’s start with counters found in some of the old mantis boxing forms such as ‘upper block/punch’, and ‘upper block/chop’, and more:

Starter Counters

Upper Block to Straight Punch, or Thrust Palm

Upper Block to Chopping Fist (Hammer Fist)

White Snake Spits Tongue - Circle In Block to Spear Hand, or Eye Plunder

Circle In Block to Thrust Palm

Circle Out Block to Ear Claw

These are simple retaliatory strikes that flow naturally off of the blocks they accompany. The key to success with these counters is more about timing, proper range (may need to close the gap as part of the counter), and seeing them real time. The last being the most difficult, and only manifests from experience drilling with feeders, and light sparring.

Adding Complexity

The following are simple counters but rely heavily on an advanced awareness of our enemies position, proper guard, good blocks, and the aforementioned timing and awareness. The overall feeder (strike thrown from the opponent) that we’re looking for is easy, but reconnoitering the enemy footwork prior to execution is critical.

In regards to executing these techniques, it is imperative that the defensive guard facets of our game are in place before applying the following counters. See further below for common fail points with these two techniques. Hint: usually attributed to a failed guard component.

These next two counters are also prevalent in mantis boxing forms that have been handed down over the generations. They are, in my opinion, some of the better counters but they are mutually exclusive; related to one another only in a general category of counter-strikes, as they require unique entries by our opponent.

Monkey Steals Peach - Opposite Arm Attack

The setup we’re looking for to initiate monkey steals peach is as follows:

My left foot is forward and my opponent is matching/mirroring my stance with their left foot forward.

The strike initiates from their left (lead/opposite) hand as they shuffle in. As you’ll see in the video, use a parry (not a block) combined with a cross circle step to their outside line.

Counter with a groin slap.

Alternatively, my opponent is instead starting from a southpaw stance. In this case I would need them to step in vs shuffle in with their opposite hand (left hand strike in our example above). The end result is the same, I get the opposing arm and foot leading the charge.

Crazy Ghost Fist - Same Side Arm

The setup for crazy ghost fist is as follows:

My left foot is forward. My opponent’s right foot is forward placing us in a southpaw position.

The strike initiates from their right hand as they shuffle in. I use a parry rather than a block, guiding the hand off to the side, being sure not to aggressively push it away. This will cause my body to twist up and reduce my counter-punch power.

Coordinate the parry with a slip offline toward the outside of their lead (right) foot.

Shuffle forward and counter with cannon fist to the liver.

As with monkey steals peach, an alternate setup is for the opponent to start with left foot forward, but they step in, rather than shuffle in. We end up with the same right arm/right foot combo we need for the counter-strike opportunity to manifest.

Scenarios

When and where to apply monkey steals peach (MSP) vs crazy ghost fist (CGF).

A. CGF - opponent shuffles forward with lead hand strike from southpaw stance.

B. MSP - opponent steps in with a rear hand strike from southpaw stance.

C. CGF - opponent steps in with rear hand strike from matched stance.

D. MSP - opponent shuffles in with lead hand strike from matched stance.

Common Fail Points

Guard

In order to apply counters successfully, especially monkey steals peach and crazy ghost fist, our guard must be intact and operating to maximum efficiency. With even one component of our guard out of place things unravel very quickly when trying to block, never mind trying to apply a counter-strike. It is possible to trade shot for shot while staying in the pocket, but this is ill advised especially against a larger, stronger, or more skilled opponent. Proper guard positioning will not only shut down many of our openings, but also lead to a successful block|counter response.

Guard Components:

Hands up - fingertips no higher than eyebrows. Preferably lower.

Elbows tucked - covers the liver and stomach targets

Staggered arms - 1 arm in, 1 arm out. This is assisted by a bladed body position and staggered stance.

Shoulder Line - our hands are lined up on the opponents shoulders creating an open channel down the centerCrossing Zones

This is usually a bi-product of our guard failing. Having to cross zones in order to block because our hands were down, or not lined up with the opponents shoulders. Crossing zones ties up our arms and forces us into awkward positions that spin wildly out of control. We’re forced at this point to bail out if we can, and try to reset our position to neutral.

Out of Neutral Position

Allowing the opponent to gain our centerline before they close range can lead to a crisis we have to contend with rather than looking for counter-strikes. While it is still possible to counter from a bad angle, our position is so poor that our strike will lack power and we’ll quickly pay for any minor success by stumbling, falling, tripping, or succumbing to the rain of blows that is sure to follow from our opponents superior positioning. It is imperative we pay close attention to keeping neutral positioning until the engagement takes place.

The 'Mantis Hand' was simply a 'Mantis Brand'

What has become abundantly clear to me through the research for my book on Mantis Boxing; along with the discovery and extrapolation of more and more techniques from within the forms, as well as the examination of the historical data surrounding the collapse of a dynastic period of a major civilization in world history, is the following…

photos by Max Kotchouro

Suggested Reading:

Prior to reading these notes below, I recommend reading my research notes leading up to this point. It will help you lay context for my observations and findings.

Research Notes: To Dissect a Mantis

Research Tool: Mantis Boxing Historical Timeline

Notes

What has become abundantly clear to me through the research I’ve been undertaking on Mantis Boxing; along with the discovery and extrapolation of more and more techniques from within the forms, as well as the examination of the historical data surrounding the collapse of a dynastic period of a major civilization in world history, is the following -

Mantis boxing as we know it today, the versions of the style passed down to us for the past 120 years, is fake.

Mantis hand posture as depicted in a myriad of forms in Praying Mantis Boxing.

Now that I have your attention, allow me to explain. Fake is a strong word, and intentionally bombastic on my part. It carries with it a harsh connotation especially when it comes to an art that is held so dear to so many loyal followers. Present company included.

Fake, implies deception on the part of those teaching or partaking in the practice of it today. This...is anything but the truth. Without those teachers, practitioners, stewards of the art, who have carried this broken and hollow skeleton forward through time, we would not have any hope of a future for this art, or perhaps even Chinese boxing as a whole. To them, we owe everything. So what do I mean then when I use the word ‘fake’?

The idea that tanglangquan had some ‘special’ technique(s) never seen in any other Chinese boxing, or martial arts style in the world, is unrealistic, fantastical, or…fake. Almost all of the ‘real’ applications (and there are many), that come out of the forms, are absolutely amazing and effective combat methods. Methods that are alive in martial art styles today; including the remaining functional Chinese art, shuai jiao, and it’s progenitor from the Steppes peoples to the north - bokh.

A majority of the forms practiced by the various lines of praying mantis boxing were created after the turn of the 20th century. They are not combative forms. They are not even made by people who necessarily knew how to fight with mantis. This is evidenced by photographs we have of said people that began documenting the art in the first half of the 1900’s.

Photo of application of Wicked Knee depicted in one of many of Huang Han Xun’s books on Mantis Boxing. Technique found in mantis forms such as Seven Star Mantis’ Beng Bu (Crushing Step). Why is he standing on one leg? Why is his opponent holding his fists at his waist?

Wicked knee depicted in a mantis boxing form.

Note: I did not say, these practitioners could not fight. I am saying, that they did not fight with mantis. As is evidenced by the photo representations of the applications depicted in their books (see Huang Han Xun’s manuals for examples). Therefore, if some of the forms are choreographed by people that did not know how to use the moves within, then they are ‘fake’ martial arts.

If the forms contain applications common to the Chinese boxing methods of the time (1800’s), and offer nothing unique that sets the mantis ‘style’ apart, then the forms cannot be what defines mantis as being mantis. The keywords and their integration into a fighter’s combat methods could however, define what it means to be a mantis boxer.

The ‘mantis hand’ itself, is fake. This is unfortunate, as it’s rather unique and extraordinary, but it is the harsh truth. It is nothing short of branding. Marketing, as I explained at Chapman University in the Martial Arts Studies talk that I gave. The fingers curling under (as seen above) are incapable of grabbing effectively, and offer no distinct advantage in fighting. As a matter of fact, it offers a plethora of liabilities.

Unfortunately, this hand posture has confused generations of worthy and dedicated practitioners of the art. Myself included. A fleeting mirage we focused on as we have sought to unlock the applications behind this ‘Mantis Catches Cicada’ posture. Which at its core, is nothing short of - ‘engarde with the hook’ (depicted further below).

The reality of this is simple - these hooks with a hand (without the fingers curling), are common holds, ties, binds, and lifts. Think of how you would hook a leg for a knee pick. How you would hook a neck for clinch. An arm for a hold. These hooks are common to many throws, and clinches in Chinese boxing as well as other martial arts the world over. Something I began to realize and wrote about back in 2013. They are not grabbing full speed punches out of the air. This quickly becomes evident when testing our art against a 3-punch-combo from a western boxer.

Mantis boxing form circa 2000.

The move applied.

Someone, at some point, took said hooks, curled the fingers, and stamped the name ‘mantis boxing’ on it. This includes other moves that have ‘faux’ hooks such as - the double hands up engarde with cat stance (mantis catches cicada seen below), curling the hands over into hooks and branding it ‘mantis’. The double rising hands that is also seen in Méihuā Quán (Plum Blossom Boxing), but without the mantis hooks exists as the opener to a mantis boxing classic known as Lan Jie (Intercept and Counter). This is a push counter takedown that is now stylized with unnecessary hooks. Something akin to performance art, rather than real fighting.

Incidentally, that opening move found in Lan Jie, is the exact opening move of the Méihuā Quán form. Minus the hooks. The closing 180 degree turn to mantis catches cicada? Also in Méihuā Quán minus the hooks. Thanks to the works of Zhang Guodong, Thomas Green Carlos Gutiérrez-García, and Ben Judkins, whose works I cited in my research on Qing dynasty totem styles, Méihuā Quán was being spread through marketplaces in Shandong and other northern provinces and heavily influenced the martial arts of the late 1800’s in China. The abundance of ‘plum blossom’ references in the mantis boxing of the turn of the 19th to 20th century cannot be ignored. An entire line of mantis was born with this moniker, forms were named after it, symbols adopted, and moves in forms were direct simulacra.

Mantis Catches Cicada posture found repeatedly in forms of the style Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳).

Cat stance engarde position found in Méihuā Quán (Plum Blossom Boxing 梅花拳), Chángquán (Long Boxing 長拳), Yīng Zhuǎ Quán (Eagle Claw Boxing 鷹爪拳), and likely more Chinese boxing styles. Often depicted as the closing move of the Méihuā Quán form precipitated by the same 180 degree turn found in mantis forms.

The photos above show exactly the same posture. The former is branded as ‘mantis boxing’ by using the hooks. Countless hours have been spent by myself, and other accomplished boxers/fighters trying to crack open the application of this move. Once you look at the prevalent styles in the Shandong region that influenced mantis boxing, it becomes apparent what this posture truly is - engarde w/ mantis. A way of stating - ‘we are mantis’.

When I use the work fake, it is not to insult, or demean any of us who have dedicated our lives to this art. Mantis practitioners are some of the most committed people I have met. The purpose, is to shine full light on the shadows. Exposing our weaknesses and laying bare a truth that we as mantis boxers all need to come to grips with. Our art stopped working a long time ago. We need to be focused on fixing it.

Embracing this truth so that we may turn our attention away from forms, styles, lineage, ceremony, and other superfluous distractions to what really matters - survival. We must turn to the task at hand. Restoring this dying martial art to relevance in the modern world. Making mantis boxing ‘real’ again. Setting it up to be the art it can truly be - a well rounded hand-to-hand combat system that works superbly in the clinch.

What Can BJJ Teach Us About Qing Dynasty Martial Arts? - Randy Brown - MAS Conference 2019

This podcast is a re-recording of a talk I gave at the 5th Annual Martial Arts Studies Conference held at Chapman University in Los Angeles, California in May 2019. The event was hosted by Dr. Paul Bowman, and Dr. Andrea Molle. A two day extravaganza of martial arts history, politics, and culture. There is amazing research into the martial arts taking place around the globe today. It was an honor to be a part of this significant event, and contribute in some small way to the Martial Arts Research Network. Below is a copy of the…

This podcast is a re-recording of a talk I gave at the 5th Annual Martial Arts Studies Conference held at Chapman University in Los Angeles, California in May 2019. The event was hosted by Dr. Paul Bowman, and Dr. Andrea Molle. A two day extravaganza of martial arts history, politics, and culture. There is amazing research into the martial arts taking place around the globe today. It was an honor to be a part of this significant event, and contribute in some small way to the Martial Arts Research Network. Below is a copy of the abstract submission for my talk at the conference to help lay context before listening.

Abstract

What Can Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Teach Us About Qīng Dynasty Martial Arts?

The continually evolving art of Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) and the journey of this style throughout the 20th century can provide insights into key elements of the Qīng dynasty Chinese martial arts, helping to demonstrate similar developments in the ‘Chinese Boxing’ systems of that era. Specifically, by following the modern evolution of BJJ, it is possible to gain insights into the sudden appearance of totem styles or subsets across China, how these anomalies become styles in their own right, and how they survived and thrived for over a century. A martial arts cross-cultural comparison of style subsets within BJJ, which have developed since the early 1990s, can be juxtaposed with the pre-modern development of comparable ‘subsets’ within Qīng dynasty ‘Chinese boxing’. On the other hand, the survival and globalization of this stylization in China differs with how developments within BJJ propagate, where instead changes become rolled into a pool of common knowledge and do not take hold as independent systems or alternative styles outside of the core art. A question needs to be asked, did ‘Chinese boxing’ of the era, have a similar common pool of knowledge? Qī Jì guāng’s manual would hint at such. Within ‘Chinese Boxing’, attributes, feats, or skills defining one fighter over another became definitive styles of their own right due to events of the time, compared to a failure in modern times for these subsets to survive independent of BJJ, even though properly vetted in the crucible of worldwide tournaments. In the Qīng dynasty a confluence of events which included rebellions, opium wars, global humiliation and the collapse of a dynasty, began to solidify these subsets as styles in China. Eventually, cultural industrialization of Chinese martial arts, notably through the Hong Kong movies, ingrained these styles into popular culture with the result being securing their legitimacy to the public eye without any evidence of martial prowess.

Keywords:

Chinese martial arts, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, Qīng dynasty, animal styles, Chinese boxing

Biography

Randy Brown

Randy is an owner and teacher at Randy Brown Mantis Boxing, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu in Acton Massachusetts. Randy has over 20 years’ experience with praying mantis boxing with additional cross-disciplinary training in various Chinese martial arts: eagle claw, Hung gar, long fist, Yang, xingyiquan. Randy has trained in 17 Chinese martial arts weapons and specializes in staff, saber, sword, and military saber and has seven years’ experience in Brazilian jiu-jitsu. He has published a number of articles in martial arts journals, including Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine and Journal of 7 Star Mantis and has competed and placed in both the U.S. National Wu Shu Championships and the International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation. Randy holds a Bachelor of Science in computer science from Franklin Pierce University. In his spare time, he enjoys writing, drawing, painting, and hang-gliding.

Bibliography

Wile, Douglas. Lost Tʻai-Chi Classics from the Late Chʻing Dynasty. State University of New York Press, 1996.

Lorge, Peter. Chinese Martial Arts from Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Silbey, David J. The Boxer Rebellion and the Great Game in China. Hill and Wang. 2012.

Tong, Zhongyi. Cartmell, Tim (translator). The Method of Chinese Wrestling. North Atlantic Books, 2005 (original 1935).

Kennedy, Brian. Guo, Elizabeth. Jingwu The School that Transformed Kung Fu. Blue Snake Books, 2010.

Leung, Shum. The Secrets of Eagle Claw Kung Fu Ying Jow Pai. Tuttle Martial Arts, 1980, 2001.

Keown-Boyd, Henry. The Fists of Righteous Harmony - A History of the Boxer Uprising in China in the year 1900. Leo Cooper, 1991.

Kennedy, B., & Guo, E. Chinese martial arts training manuals: A historical survey. Berkeley, CA: Blue Snake, 2008.

Laurent Chircop-Reyes. Merchants, Brigands and Escorts: an Anthropological Approach of the Biaoju ffff Phenomenon in Northern China. Ming Qing Studies, WriteUp Site, 2018, Ming Qing Studies, 2018, http://www.writeupsite.com/eng/ming-qing-studies-2018.htmlff. ffhal-0198740

Article on Biaoju Companies - https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%90%8C%E5%85%B4%E5%85%AC%E9%95%96%E5%B1%80/8761785

E. Henning, Stanley. (1999). Academia Encounters the Chinese Martial Arts. China Review International. 6. 319-332. 10.1353/cri.1999.0020.

Interview with the last Manchu archer - By Peter Dekker, January 23, 2015 - http://www.manchuarchery.org/interview-last-manchu-archer

Library of Congress maps - https://www.loc.gov/maps/?c=150&fa=subject:maps%7Clocation:china%7Clanguage:chinese&st=list

List of Rulers of China - Metropolitan Museum of Art - https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chem/hd_chem.htm

Li San Jian - http://www.shm.com.cn/special/2015-07/22/content_4365668_2.htm

McCord, Edward A. The Power of the Gun. University of California Press, UC Press E-Books Collection, 1982-2004 - https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft167nb0p4&chunk.id=d0e288&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e288&brand=ucpress

Guodong, Zhang & Green, Thomas & Gutiérrez-García, Carlos. (2016). Rural Community, Group Identity and Martial Arts: Social Foundation of Meihuaquan. Ido Movement for Culture. 16. 18-29. 10.14589/ido.16.1.3.

The Mantis Cave - Fernando Blanco - http://www.geocities.ws/mantiscave/fernando.htm

The Taiping Institute - http://www.taipinginstitute.com/courses/northern-central-plains/tanglangquan

Judkins, Ben. Lives of Chinese Martial Artists (13): Zhao San-duo—19th Century Plum Flower Master and Reluctant Rebel - https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2017/04/20/lives-of-chinese-martial-artists-13-zhao-san-duo-19th-century-plum-flower-master-and-reluctant-rebel-2/

Judkins, Ben. Research Notes: Xiang Kairan on China’s Republic Era Martial Arts Marketplace - https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2016/08/14/research-notes-xiang-kairan-on-chinas-republic-era-martial-arts-marketplace/comment-page-1/#comment-81216

Perdue, Peter C., Sebring, Ellen. The Boxer Uprising 1 - The Gathering Storm in North China (1860 - 1900) - https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/boxer_uprising/pdf/bx_essay.pdf

The Worst Natural Disasters by Death Toll - Contributed by Administrator - June 15, 2007 Last Updated April 06, 2008 - http://www.armageddononline.org

Professor Peter Lorge's keynote, 'The invention of "traditional" martial arts" - given at the July 2017 Martial Arts Studies Conference, Cardiff University - https://youtu.be/9Y_1tKVvwNc

Tear Down the Monkey - Fight Stance Revamp

A critical analysis of the fighting stance we've been using for years. And why I got rid of it.

I recently went through some changes in my teaching and practice. One of these recent changes was in our fighting stance. The reasons for these are many, and too lengthy to explain for these purposes. However, the root of any changes I make are always born of a desire to improve things for myself and my students.

Let’s compare the stance we were using for years, the Monkey Stance, with the…

A critical analysis of the fighting stance we've been using for years. And why I got rid of it.

I recently went through some changes in my teaching and practice. One of these recent changes was in our fighting stance. The reasons for these are many, and too lengthy to explain for these purposes. However, the root of any changes I make are always born of a desire to improve things for myself and my students.

Let’s compare the stance we were using for years, the Monkey Stance, with the 3 Dimensional Stance, 4-6 Stance, or 40/60 Stance common to other Chinese boxing systems from the same region and era.

Monkey Stance (Hóu Shi 猴势)

Monkey Stance

The ‘monkey stance’ is found in seven star praying mantis boxing, plum blossom praying mantis boxing, and supreme ultimate praying mantis boxing. Although used within these branches of mantis boxing it is not necessarily a ‘sparring’ stance. It shows up within moves in the boxing sets of old, but usually aligns with the execution of specific techniques. More common in these old forms, is actually, the bow stance, or mountain climber stance.

Upon recent discovery, these monkey stance techniques are typically leg wrap takedowns which necessitate this stance in order to shadow box the move absent a partner, without falling on one’s face. I had fully integrated this stance into my fighting and movement patterns after having learned it from a coach I worked with for years. He taught/used this monkey stance in fighting predominantly because of the correlation he found in Western Boxing. However, the latter is usually in a much higher posture due to the lack of necessity in defending kicks and takedowns.

The higher posture found in western boxing allows for increased mobility when using this stance/footwork, and has less detrimental effect on the fighter’s balance. The feet are closer together which leaves the stability of the boxer mostly uncompromised. This has issues in a mixed martial art arena, which is why you do not see MMA fighters using this stance.

When used as a lower stance (as we were doing), the monkey stance is rather unstable and rife with problems. Least of which is it’s mobility. Let’s rip it down so we can understand the inherent strengths and weaknesses of this ‘stance’.

Strengths

Offers solid defense capabilities - decreased profile for target acquisition from the opponent.

Forward position offers quicker range to target - a 50/50 weight displacement puts the range to target of the striker closer to their target. This helps get hands on the opponent faster and offers a range assist for smaller fighters.

Increased mobility - this is only active when the fighter is in a high stance. Otherwise, this is negated.

Protects the Knee - this is one of the finer points of this stance in my opinions. With the knee over the toe, the boxer is almost immune to cross kicks and side kicks which are designed solely to attack the knees. Proper execution of this stance nullifies this threat.

Good in the Clinch - when engaged in grappling, the 50/50 position of the monkey stance, and the lowered center of gravity are where this stance shines the most. A stance with weight distribution forward, or behind this 50/50 center of gravity point, causes us to be open for pulls, pushes, and a variety of throws. This, in my opinion, is where the monkey stance becomes necessary, and relevant.

Weaknesses

Unstable - this stance is extremely unstable. Especially from lateral attacks such as haymakers, which are an extremely common strike even from novices. The stance can become stable with a great deal of tweaking and perfection, but the amount of time required to do this, certainly nullifies its benefits, which are few compared to other stances. The ease of which a smaller fighter can be rocked and toppled makes this a dangerous choice when looking at stances to use in hand-to-hand combat.

Difficult for beginners - there is a massive learning curve with this stance. When sitting in this stance to maximize its effective traits, it is extremely finicky. Knee over toe, back foot angle/position, hip alignment, shoulders over hips, balls of the feet, hips dropped. Remembering all of that, while trying to move in a completely foreign manner that is counter to our human movement patterns, can take a casual practitioner years to get down. With diligent focus, the stance still requires hundreds of hours of training to overcome and perfect the stability and mobility deficiencies.

Decreased mobility - when hunkered down in this stance it is lacking mobility in order to maximize defense. While defense is great, it is not the endgame. The ultimate goal, is to defeat our opponent(s). Imagine being faced with multiple attackers, and sitting in a fighting stance that creates a 50% speed reduction. Or you are in a cage fight, facing a mobile, and speedy opponent. You won’t keep up.

Vulnerable to Leg Kicks - The forward 50/50 position for the center of gravity, causes the leg to become a closer target for our opponent’s leg kicks. Additionally, more weight on the forward leg, causes an extreme delay in response time in getting the leg up to check, or avoid an opponent’s leg attack. This is the number one attack I would use against someone in this stance. Destroy leg. Compromise their mobility, and take their will to fight.

Exposed Striking Power - in order to generate maximum power in this stance, a fighter must learn to shuffle with each strike, or twist/rotate the hips when throwing off the rear hand. This is common in western boxing for producing awesome striking power. However, when we twist and throw ‘long’ punches/strikes we create a longer opening in our defense that is susceptible to counter-strikes. This window of opportunity can be an issue against a seasoned opponent.

Takedown Defense - if you were to classify each type of throw, trip, takedown that exists within martial arts styles the world over, and then categorize them based on frequency of use, the single and double leg takedown would be at, or near the top of that list. These are common weapons in the arsenal of wrestlers the world over. The monkey stance, becomes necessary within the clinch, but when used prior to the clinch phase, it creates a leg position that is extremely vulnerable to single/double leg takedowns. Additionally, the 50/50 weight distribution again creates a speed limit on the ability to sprawl. A veteran shoot fighter that is highly adept at setting these up, will close the gap from striking range to the takedown in the blink of an eye. Any speed/range advantage we can have in striking range can be a deterrent against these attacks. This stance is not the choice selection when it comes to this.

The Three Body Solution - San Ti Shi (三体势)

Used in a derivative of Mantis Boxing known a 6 Harmony Praying Mantis Boxing, and a newer (1900’s) subset of that known as 8 Step Praying Mantis Boxing. The 6 Harmony line has roots in another style of Chinese boxing, that is derived from Liuhe Xingyiquan (6 Harmony Mind Intent Boxing). A system taught by the Dai family in Ming dynasty who owned a security/escort company known as a biaoju. This explains why this line has an entirely different stance than the other branches of mantis boxing.

The concept is - simple striking with solid footwork designed to maximize power. The striking was used in conjunction with blocks/intercepts and could be blended together for combinations as needed. Throws and other techniques were included in the system, but it was overly simplified to keep the training methods efficient and effective. Something you would want when training security and bodyguards.

The stance used in ‘mind intent boxing’ is called a San Ti Shi (three dimension stance 三体势) and while not unique to this one style, it is effective. It appears in other Chinese boxing systems originating from northern China as well.

In my opinion, this is a much better stance for a variety of reasons. Hence why I began adopting it in my system and discarding the monkey stance except when grappling. The following breaks down the advantages and disadvantages of the three dimensional stance before we get into the details on proper execution.

Strengths

Stability - this stance is incredibly stable, especially when compared with the monkey stance. The 40/60 weight distribution, with hips dropped offers a stable platform for striking, kicking, or defending even from lateral angles of attack.

Ease of Use - one of my biggest criticisms of the monkey stance is it’s long and finicky learning curve. For beginners who are training 2 to 3 hours per week, the san ti stance is much easier to learn, and execute. Unlike the monkey stance, it takes very little maintenance to get people on board with the concepts and application of it.

Power Generation - next to stability, and ease of use, this is probably one of the greatest advantages of this stance. The power generation capacity from this stance versus the monkey stance is phenomenal when looking at a fixed stance platform to compare. The monkey stance can generate power as well, but usually at cost of defense, or stability when committing to the twist execution to produce the force. The 3-dimension stance however, can outperform without compromising the integrity of the defense/position of the fighter.

Kick Defense - the round kick is a powerful weapon in a boxers arsenal when used as to attack the lead leg of the opponent. Opposite the monkey stance, the three dimension stance offers a quicker reaction time to move our leg, or shin-check the opponent’s attacking leg. When it comes to groin kicks, the narrow stance of the san ti offers defense by itself. Once again, the lighter weight on the front leg allows for a quick reaction time against leg attacks, knee attacks, or groin attacks.

Takedown Defense - this is specific to shoot takedowns such as single leg, double leg, or rushing/tackle takedowns. The rear sitting san ti stance, offers a larger timespan to initiate a sprawl, or rearward step to avoid these takedowns. The forward weight of the monkey stance was not useless, but the timing was harder to get down.

Range Manipulation - another exceptional advantage to this stance, is the ability to manipulate range. The slight rearward weight distribution offers an appearance to the opponent that we are further away than we really are. The lead foot position indicates our true range to target. We can therefore, get that position across the ‘critical distance’ line of our opponent with them unaware that we moved in. This allows for us to gain range advantage on an offensive assault. Additionally, as mentioned above, the defense is also assisted with the range increase offered by the rear sitting san ti stance compared with forward-weighted stances.

Weaknesses

Knee exposed - if your stance sits too far back, meaning you violated the 40% weight on the front and 60% on the back, it exposes the knee. This is improper or lazy execution and can cost you your knee if you are not careful. Be mindful of the cross kicks, and side kick attacks your opponent may throw at your foreward leg and you should have plenty of time to defend if that happens. To nullify this, train the proper weight distribution and sink your hips. This will keep the front knee rounded, arcing against your opponents thrust force.

Mobility - the stance is less mobile in circle patterns commonly found in boxing and MMA bouts. Use it for engagement purposes only, once you have crossed ‘critical distance’ and committed to your assault.

Clinch Deficient - this is not an optimal stance inside the clinch. The weight being back makes us susceptible to being pushed over backward. Once the clinch happens, shifting to the ‘weight-forward’ advantage offered by the monkey stance, bow stance, or horse stance when in the flank, is a better tool for the job.

Mechanical Breakdown

Weight Distribution - 40% of body weight on front leg. 60% on the back leg.

Center of Gravity - CG should be slightly rear of the 50/50 mark. Sink your CG by dropping your hips 3 to 4 inches. This will also bend the knees and create a suspension system in your legs allowing for better balance, and mobility.

Front Foot - aimed at target, or direction of travel.

Rear foot angle - it is imperative for stability that the rear foot be at or around 45 degrees angled off from the front foot.

Width - heel of the rear foot is in line with the heel of the front foot (see diagram).

Splitting the Floor - Focus the pressure on the pads of feet. When hips are dropped, it should feel like you are splitting the floor between your feet.

Posture - sit up straight. Shoulders over hips.

The san ti shi is an all around better stance as we can see from our strengths vs weaknesses evaluation above. The ease of use, striking power increase, kick defense capability, improved range manipulation, and takedown defense make this an optimal fighting stance far superior to the monkey stance. Therefore, it’s a no-brainer from a coaching perspective, as well as a fighter’s methodology. You can see why we switched.

Rise from the Ruins: Embarking Into A Dying Art of Boxing

An Essay on my Early Years in Chinese Boxing Dance

Martial arts forms (kata, tào lù) are more plentiful today than in any time in history. They are widely disseminated in a variety of martial arts schools/styles across the United States, and around the world. A majority of ‘traditional martial arts’ competitions today, are centered around stylists competing with their form of choice. One is hard pressed to enter a school of karate, kung fu; kempo, tae kwon do; or tang soo do, etc. that isn’t consumed by a curricula filled with form after form. Once you complete one form, you’ve earned the ‘privilege’ to learn another...and another...and another.

Years into my training, I went on to scorn these empty shells. For quite some time actually. One reason I held such admonishment toward ‘forms’, was having…

Finding the Mantis

I came across the art of Praying Mantis Boxing in of all places - New Hampshire, USA back in the 1990’s. I was correcting course in my life and on a quest to empower myself with martial arts training and the skills to know how to handle myself. A desire of mine since childhood. I immediately fell in love with the art, even in it’s corroded state.

Sadly, time has not been kind to this, and many other Chinese boxing systems. Much damage has been done over the past century or more, as these arts were no longer used for combat. By the time I began my training, it was difficult to tell what Mantis Boxing was in its original manifestation.

What remained was largely boxing sets (choreographed fighting moves in the air known as forms/kata/taolu), myriad drills, and a plethora of archaic Chinese weapons techniques of a bygone era.

Due to this decayed state my journey early on with this art was difficult and fraught with challenges in finding answers, or seeing an effective use of these movements in sparring/combat. Thankfully, we do have those who carried the torch over hundreds of years; bringing with them the keywords of the style as well as the old ‘boxing sets’ which allow us to view into the past.

I have dedicated over 20 years to mantis boxing, as well as other stand-up fighting arts in a quest to reconstruct the art so that it is intact for my students going forward. Through traveling, studying with experts, training, competing, teaching, sparring, researching; anything I could find that would yield improvements. We move forward with methods so that others, like you, can receive a fighting art that is versatile, effective, and well…quite frankly - RAD!!!

My efforts to ultimately reshape, redefine, and revolutionize the art have created a new version of mantis boxing that is relevant for self-protection in modern times. This last part being of great import to me. I believe any martial art should be applicable and functional. Ensuring not only its own survival for future generations, but also the survival of its practitioners.

BOXING SETS

Throughout my martial arts career I have had many opinions on forms/boxing sets. These viewpoints have shifted like the swirling tides along the rock-strewn coastline of Maine. Early on, when I began my training I was heavily invested in these sets. They were, after all, the primary method of transmission for the art that I chose to study - Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳), and before that, Tae Kwon Do.

Mantis Catches Cicada - circa 1999

Mantis boxing was handed down to me by my early teachers, and their teacher’s before them, with forms as a primary method of transmission. Completely absent of the mechanical inner workings that made these moves functional with live opponents in actual hand-to-hand combat. In all fairness to the first mantis coach I had, was up front with me from the beginning about this. I was under no illusions.

Martial arts forms (kata, tào lù) are more plentiful today than in any time in history. They are widely disseminated in a variety of martial arts schools/styles across the United States, and around the world. A majority of ‘traditional martial arts’ competitions today, are centered around stylists competing with their form of choice. One is hard pressed to enter a school of karate, kung fu; kempo, tae kwon do; or tang soo do, etc. that isn’t consumed by a curricula filled with form after form. Once you complete one form, you’ve earned the ‘privilege’ to learn another...and another...and another.

Years into my training, I went on to scorn these empty shells. For quite some time actually. One reason I held such admonishment toward ‘forms’, was having learned over fifty of them in my first seven years dedicated to wu shu (martial arts) training.

As soon as I would finish one form, I would be handed another; whether by my request for some shiny new toy I was enthralled by, or a suggestion by the instructor(s). It became impossible to remember all of these sets, and far too time consuming to practice them all; little did I understand why at the time.

When it came to fighting and sparring in the martial arts schools I attended, the combative application was entirely disembodied from these forms; like a warrior’s sword detached from it’s handle - once upon a time a dangerous weapon to be feared, now - a toothless tiger.

Crossover from form to fighting never existed in the schools that I trained in. We would warm-up, practice movements, shadow box, and spar the last few minutes. When it came time to spar with classmates, it usually manifested as ‘bad kickboxing’. To be fair to these coaches, their passion lied with what they were teaching - forms, not fighting.

I kept sparring as much as possible, and competing in matches. I became increasingly frustrated over time. I would ask myself - “wasn’t the point of martial arts to learn how to defend yourself? Wasn’t the ultimate goal to become empowered? To know secret ways to disable attackers, fend off bullies, submit miscreants that wish harm upon us, or protect our families?” I was profoundly confused by the training practices I was experiencing, versus what I had envisioned martial arts being meant for.

COMBAT ARMS

Flight School - aka ‘Fight School’ - Alabama 1990

Having been in the military for a short period of my life, I was used to an environment built on training for ‘combat’. We certainly didn’t pretend to drive tanks, or fly invisible helicopters, fire imaginary bullets downrange, or use toy weapons. Lessons on my martial arts path were not adding up with my life experience. Why was a bulk of my time training, just pretending to fight opponents in the air???

While I was stationed in Texas, I briefly undertook the study of taekwondo until my military units’ training schedule was ramped up and I could no longer juggle it in. It was enjoyable at the time, but certainly wasn’t my favorite martial art style. I had a good teacher, and I enjoyed my time there (however brief), but the art was too simple, and too linear for my taste. However, to the instructors credit, in those classes we spent a bulk of our time sparring.

Years later, as I was well into my Chinese martial arts training, I knew something was amiss with the way I was being trained. I tried taking moves from some of the forms I had learned, and experimented with them while sparring in class. This was often met with punishment being doled out by my opponent’s barrage during my risky ventures. Still, I tried to pull them off, but rarely did I find success.

Instead of introducing something new into my game, it became increasingly easier to rely on a few well-timed tricks, and speed/power to overcome my opponents. Sticking to the attacks/counters I was already good at. Reinforcing my current skills rather than growing as a fighter/boxer/martial artist.

Along the way I had decided, with the encouragement, and support of those around me, to become a martial arts teacher for a living. I was instructing at another school while this metamorphosis was taking place, and I opened a school with a friend of mine (2004). Off we went. Things did not improve; quite the opposite actually.

MIRROR INTO THE SOUL

Chris and Vincent - Tournament - Fall 2007

Now that I was teaching others full-time, the disconnect became crystal clear. I no longer had only myself to worry about, but my reflection staring back at me day in and day out. That reflection was my students. The truth became less than encouraging. My students would learn to move, perform cool looking forms, win competitions, but their fighting skills were no match for other martial artists such as boxers, wrestlers, judoka, etc.

I would ask myself - “Why someone taking western boxing for 6 months, could decimate a practitioner from kung fu, karate, kempo, tae kwon do, etc.?” In many cases, the latter had been training for years, or in some case decades.

I was thoroughly frustrated. I could suffer this no longer. We can be either part of the problem, or part of the solution. So I began to change the way I was teaching. I turned the focus of my classes more heavily on qín ná (the Chinese submission art of bone/joint locking and seizing).

In my early training, I had spent 4 years studying this discipline in tandem to my forms regimen. Dedicating multiple hours each week with partners in my first mantis school, and training with friends on the side. I felt better. It wasn’t perfect, but at least this was drilling with live people, and I was giving my students something that felt like martial arts/self-defense, rather than dance.

Jess and Mike - 3 Section vs Staff - 2005

I incorporated more ‘2-person’ hand-to-hand, and weapon sets from kung fu. Again, thinking that at least these had combative moves that involved a live partner to test against. All the while, I was still voraciously searching for answers.

I made it my mission to figure out how these forms worked in fighting; continuing my research; sparring as much as I could with friends that were traditional martial artists, and who were also frustrated by the norm. I turned the pages of tome after tome, reading historical accounts, watching videos. Any sources I could find. I turned my attention and focus to seeking out the core/roots of each system. Then…something enlightening happened.

A pattern began to emerge. I noticed a common theme while traversing my archaeological quest. How these styles began…

Tángláng Quán - two forms.

Yīng Zhuǎ - two forms and one partner set.

Tàijíquán - zero forms.

Hóng Jiā (Hung Gar 洪家) - one form.

Bāguà quán (8 Trigrams Boxing 八卦拳) - zero forms.

Xínyìquán (Intent Boxing 形意拳) - zero forms.

The writing was on the wall. In giant print. None of these styles started out with…so...many...forms. It was now obvious to me what I needed to do. Purge!

I embraced the ‘less is more’ philosophy. Even though, and unbeknownst to me at the time, I was still clinging to too much material. I discarded a bulk of the forms I had learned over the previous seven years. I no longer practiced, or taught them.

I sought out the core forms of the arts that I really enjoyed - Praying Mantis Boxing, Eagle Claw, Tai Chi, and Xing Yi. My intent being to ‘mine’ these forms for applications. To see what the original methods, movements were, so I could reconstruct these arts. Lofty goals to be sure, but I was not to be deterred. I was too invested at this point.

Traditional Long Weapons - Nationals Qualifiers - 2004 - Hershey, PA

After repeated polite inquiries with various mantis boxing teachers around the country, I was rebuffed by taciturn ‘masters’ unwilling to share their art. They behaved as if these forms were valuable magical secrets. As if I was asking for their priceless gems.

These teachers clearly coveted their core forms, like a mage who possessively guards their spellbook. I truly failed to comprehend why teachers were so disinterested in...teaching. I was ready and willing to learn! Why were they not helping me?

I had been learning forms a dime a dozen over the years, why were these such prized antiquities? Instead of welcoming an interested student, people were possessive; greedy, condescending, and cold. Again, rebuffing my ideals of what a martial artist is about.

During my journey, I learned that one “Grand Master” went so far as to try and sue people for stealing his forms. His organization actually attempted to copyright them. Other’s demarcated forms with fake moves so they would know when someone ‘stole’ it from a video, demonstration, or tournament. Marring the art, and further tainting it from its original intent and true purpose. This was chaos incarnate, and I simply did not understand it.

Martial arts in general, and forms specifically, are not something one can ‘steal’. One can copy someone’s form, but if the ‘thief’ does not do the work, or fails to comprehend the intent of the moves within, they have no score.

If the purported burglar does the work - learns it, trains it, tries to perfect it; studies it thoroughly, then they have been taught. Perhaps, without them knowing they’ve been taught. As a teacher, or even a practitioner that wants their art to survive, is that not our ultimate goal and purpose?

Snakes Creeps Down (low single whip) Taijiquan demo - circa 2006

I continued on. I was teaching Tai Chi, and finding it difficult to find any sort of consistency from one person to the next when it came to the movements. Additionally, I could find no one that knew what these moves did, so there was no litmus test to know if a movement was ‘right’, or ‘wrong’. Every reason someone had, seemed esoteric, and subjective. Like judging dance, or art.

Xingyiquan was another focus of mine during this time. I enjoyed the premise behind it. I was told it was highly destructive, energetic, explosive, and aggressive. That it was a badass style of Chinese boxing. I was into that! A coach that introduced me to it, thought it would be a good fit for my…temperament.

Again, it seemed like the standards for success in xingyi, were completely arbitrary. The only ‘depth’ I was finding, was “sit in your san ti (3 dimensional shape) stance for 30 minutes a day.” Aside from that, I wasn’t told how to fix anything, or how to get better at xingyi. Later I realized - because you need to HIT things to really get it!!!

I sought out more coaches in these arts. I was successful in finding a tàijíquán/xingyiquan ‘master’; or so I thought. I attended one of his New England workshops and saw a glimpse of some power generation techniques in his Xing Yi that was of interest to me. I was told “he knows his stuff.” I thought there was something there, so I delved deeper.

I cobbled together some money and traveled to NYC to train with him. I hosted him for a few days at my house and school to help him share his art with my students. To hopefully glean greater technical knowledge from him on how these two arts functioned in combat.

It turned out to be forms, and hocus pocus. The tàijíquán was more incessant drumming of the most mundane minutiae. Where the hands should be aligned to maximize the ‘chi’. How one’s thumb position next to the quadricep was somehow important for mystical energy alignment. No accompanying demonstration of combat application to show why this mattered; nevermind how it was relevant in a real fight.

The renowned xingyiquan, a style known for its destructive capacity, and reputation for general badassery, was also more ‘air-fu’ (martial arts done in the air). Never hitting a punching bag, or pad. Never sparring. Never blocking and hitting. Just more chi (cheese). More pseudo-science. More nonsense. I left it behind.

In addition to the aforementioned individuals foul bathroom habits, and erratic/obnoxious behaviors, this arrangement was not working out to my satisfaction. Could ‘anyone’ in Chinese martial arts actually fight? Using Chinese martial arts techniques? I was growing more and more disenchanted.

Staff vs Staff - circa 2006

I returned to my research and training. Buying any books I could find. I read over 100 books on Tàijíquán, most of them a complete waste of time. It’s amazing how many words have been written about nothing.

I found the other arts lacking in content altogether. At least to my favor, tàijíquán is well documented. The most widely proliferated Chinese martial art in existence. Unfortunately, much of this is without practical meaning, and comprised mostly of esoteric beliefs, or lacking clarity of purpose. Whether this is intentional, or through innocent ignorance is certainly a matter of debate.

I took to searching for videos of the core forms of the styles I had chosen. For mantis boxing, I was able to find one of Bēng Bù (Crushing Step), but had no such luck with Lán Jié (to Intercept 拦截) , or Bā Zhǒu (8 Elbows 八肘). I ordered videos from China, familiarizing myself with the Chinese characters enough that I could search for books and VCD’s containing these sets, or anything close to them. I signed up for a Chinese class to assist in my quest.

My language venture did not last long. It turned out to be the same misguided approach to teaching language that is rampant in public, private, and even collegiate school systems across America even to this day. Grammar first. Years go by, and one is still unable to speak fluently, or converse with a native speaker. It is odd, that this failure of a student to speak, is not a measure of success for a language arts curriculum, or a teacher’s capabilities...

I digress. It so happened that in my research, I had come across an excellent resource of knowledge - an online forum for mantis boxers. Rich, and fascinating conversations took place in this venue, people seemed to be sharing knowledge and communicating their ‘secrets’ without reservation. I visited it from time to time, never saying much as they seemed far more knowledgeable than I; and there existed an hierarchy of lineage holders that I was not part of.

One day, I read a thread where an individual was chastising and insulting anyone who learned from a video. This individual was particularly demeaning, condescending, and harsh in their criticism. Stating matter of factly, that “anyone interested in learning mantis should only be doing so from qualified teachers; certainly not from video!!!”

This infuriated me. Who was this person to dismiss one of the three ‘primary methods of human learning’ (verbal, kinesthetic, and visual)? What position of expertise did they hold in life to stand up and blatantly proclaim that personal instruction (which I had experienced plenty of), was the ONLY way someone should, or could, properly learn. I balked at this notion. I broke my silence and chimed in.