A Daemon in my Dojo

The afternoon sun turns to shadow early as the solar cycle wanes and we fast approach the winter solstice. I was finishing my training and sitting down to meditate when the visitor walked in.

A new visitor arrived in my dōjō today, a stranger from a far off land. It is the beginning of autumn in the year 2012. Dōjō, or ‘way place’ in Japanese, a place to study the way of ‘something’, typically martial arts. In Chinese martial arts we call it a wǔ guǎn (wǔshù guǎn), or martial hall, the place in which we gather for the study martial arts.

The afternoon sun turns to shadow early as the solar cycle wanes, and we fast approach the winter solstice. I was finishing my training and sitting down to meditate when the visitor walked in. Lately I have been consistently practicing meditation as a post training routine to clear the mind, to take inventory, and to stay grateful.

It has been thirteen years since I began practicing Praying Mantis Boxing (tángláng quán), and a bit over a year since undertaking the art of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (B.J.J.). I recently competed in my first BJJ competition as a newish white belt. Currently, I am training and coaching six days per week, as has been the case for the past eight years. When I’m not teaching or occasionally unfurling my wings to deftly dance off a cliff to reach for the clouds above, I pen articles on martial arts as thoughts and ideas materialize that may be of use for others on this path. I have been cross training in other arts for a few years, nothing serious prior to BJJ, but enough so that I have been experiencing modalities outside of Chinese boxing arts; seeing a broader picture.

I sit regulating my breathing, trying to focus my mind. A bright warm light washes over me as the door opens. The stranger interrupts with abrupt words that leap forth like a flash of briny sea water surging to shore on the rush of high tide. These noises flood my brain. At first I am annoyed at this intrusion, and try to ignore it for a moment of solitude. Then, I pause to listen to what he said to me.

As my mind churns over the information it feels as if this visitor is casting a bright spotlight into the deepest umbra in my brain. He begins to spout emphatically about Bēng Bù, crushing step for short, but the longer meaning is – steps to cause the enemy to collapse and fall into ruin. Bēng bù is a shadow boxing set found in styles of mantis boxing, I have been practicing this set since 2005 learning five or more versions from the various lines of mantis boxing, part of my quest to decipher the true intent behind the shadow boxing shell transmitted through mantis boxing lineages for the past one hundred years, or more. I’ve vigorously searched for the hand-to-hand combat applications originally intended by the creator(s), wanting my own continuation of this boxing style to be effective in fighting. Something I have rarely seen thus far.

Eventually I settled onto one version of bēng bù that I train a few times per week, occasionally spending time mulling over the potential applications within my head. The stranger's words snap like a bolt of lightning crackling through my mind. Riding along the spectrum of light his question crackles forth: “Why is bēng bù, like so many other Mantis Boxing forms, begun with and finished with the move, ‘Mantis Catches Cicada’?”, he continues on, “This is not a finishing move to end a fight, so why would this technique of all of them be laid out in form after form almost as bookends?”, “Is this just stylization? Is it a meaningful application?” His questions intrigue my mind, I begin chasing the lightning along its incongruous path.

Code breaking comes to mind, more specifically ciphers. I reply to the stranger, “A cipher used to crack open an ancient codex. A boxing form, in this case crushing step, a set of choreographed moves from a boxer of old, is this the codex and Mantis Catches Cicada the cipher? Perhaps this move is ‘the key’ to unlock the applications within the form?” I begin traversing the halls of the labyrinth in my mind, searching every corner, opening every door, looking at each move in bēng bù from a ‘two hooks’ (neck and arm, or colloquially known in fighting circles as a ‘clinch’ position.

The dialogue and the air around this impromptu visitor, ripple with electricity in the air. I struggle to keep pace with the trove of possibilities his questions raise. As I peruse the catalog of choreography in each road of the set, I conclude that some of the bēng bù boxing moves could certainly function from this position, but others clearly not. The questions then enter my mind, “Where is he from?”, “What, or who, is the source of visitors knowledge?”, “How did he happen upon my dojo?”. I asked his name. “Wang”, he replied.

Wang was a pesty guest, talking incessantly his entire visit. “Does he ever shut up?”, I wondered to myself silently. A wave of empathy washed over me, he did travel from afar, and spent so much time alone unable to talk to anyone about this subject matter. A topic that must be yearning to escape the prison of his mind.

Wang spoke day and night, following me home after classes. He had nowhere else to stay on his visit, I felt compelled to open my home to him, annoyed at times, but grateful for his illuminating thoughts and inquiries.

During his stay I rarely caught a wink of sleep. Wang sat next to my bed at night incessantly rambling till the sun came up. With no choice I lay awake listening to the chatter, staring at the ceiling, throwing off the sheets in exasperation, pacing the room, and spending nights shadow boxing while Wang rolled on. I caught a wink of shuteye here and there, only to rise early again the next day. A true insomniac, Wang did not sleep, obsessed with his ideas which spawned forth like seven hundred baby mantids hatching from an ootheca in the midsummer garden.

With seemingly nowhere else to be, Wang stayed for weeks, revealing a series of mantis boxing positions and hand-to-hand combat applications I had never considered before. I immediately went to task testing these in drills, sparring, and grappling as Wang sat looking on in satisfaction. A new world arose around me; a schism manifested, a cataclysmic shift in my worldview of fighting.

Wang, seeing my progress, bid me farewell for the time being, proclaiming as he exited my dojo, “Perhaps I’ll return, but for now, you need to chew for a while before we can dine again.” I bowed to Wang in gratitude, and wished him well on his travels. Thus concluded my first visit with the daemon who sojourned to my dojo.

Discovering the 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing

The above short story is an allegory based on real events. An episode in my life back in 2012 consiting of an explosion of ideas and thoughts. The dōjō is not the one I train and coach inside night after night, but rather the one I spend far more time in, the one inside my mind.

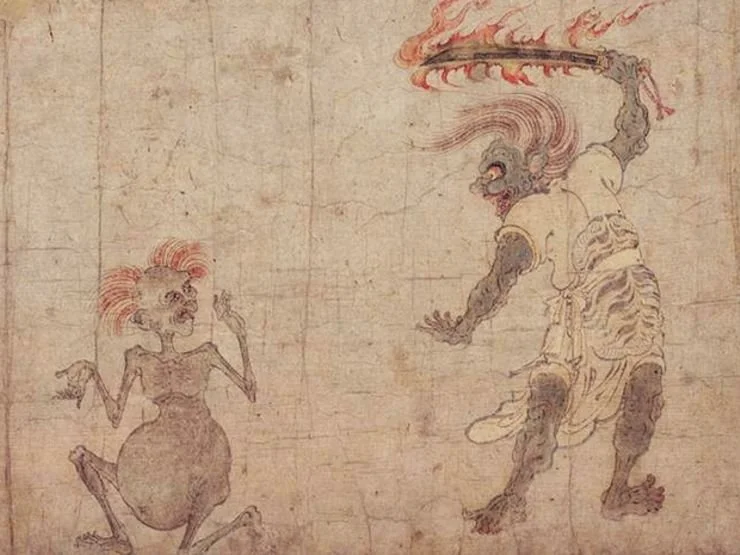

My daemon, Wang, is based on Wang Lang the mythical founder of mantis boxing. The man accredited with the origin of this boxing style hundreds, or thousands of years ago, depending on who you listen to. You can read more about Wang Lang in an article I wrote on his possible accreditation to the art here: The Apotheosis of Wang Lang

Prior to this experience I had little in the way of instruction or conversance with the 12 keywords of Mantis Boxing. I certainly knew of them, as most serious and long term practitioners of the art do, but I had yet to delve into them. From my observations and experiences any information regarding these keywords, and conversations surrounding them amongst mantis boxers and coaches, devolved into arguments over what the ‘correct’ keywords are, and their true meaning.

The thoughts I had on ‘mantis catches cicada’ were real. However, while this was a ground-breaking revelation that sparked an age of discovery, and helped lead me onto a fruitful path, years later I debunked this theory when my research exposed mantis catches cicada as nothing more than a — brand moniker, rather than an actual fighting technique. A mantis boxing en garde to proclaim, ‘We do mantis.’ This moment in time though, when all these thoughts began to appear, shifted my brain into thinking of each move from a whole new pillar of fighting — wrestling/grappling.

My daemon helped me to see the first three of the twelve keywords of mantis boxing with new eyes. I began to commit pen to paper, to record these thoughts as they manifested. It crawled from my pores with an unstoppable force. We took photos. I wrote my first quasi-article on ‘What is Praying Mantis Boxing’, now titled The Heart of the Mantis, a rough experience. This idea that wrestling was an integral part of mantis boxing was scoffed at by the mantis boxing community, and some were extremely rude in their rebuttals. I charged forth anyway, fully committed and stalwart in my belief that I was on the right path. As with any new endeavor, I was getting my legs under me as I awoke from a slumber.

Over the ensuing years Wang would come by for a visit from time to time. If I was not paying attention he would splash hot tea on my brain, burning me so I would once more bring my full attention to bear on what he had to say. As I continued boxing, grappling, and progressing in BJJ I unlocked more and more positions and fighting applications. An increasing number of the keywords unlocked before my eyes.

I noticed a similarity with other grappling arts and recalled Gichin Funakoshi remarking in his book Karate-Do that I read back in 1999, that Kara-Te (way of the Tang Hand) was a blend of techniques Okinawan nobles would bring home from southern China during the Tang dynasty, and blend them with their indigenous fighting arts. Years later finding out those indigenous arts were wrestling.

As we sat in the garden sipping tea on one of Wang’s visits, he asked me: “What were China’s indigenous fighting arts?” I began to delve into the history of the Chinese martial arts ecosystem as a whole, coming across...Bokh, the Mongolian wrestling arts still alive to this day. This was enlightening especially since many techniques looked similar to postures found within Mantis Boxing (and other styles) forms of Chinese martial arts that I had studied over the years, to include: taijiquan, eagle claw, long fist, and more.

Bokh, and its history/influence on Chinese culture when the Mongols invaded and took over China during the Yuan dynasty, made me grossly aware that Mantis Boxing along with other Northern Chinese Martial Arts styles that I had studied over the years, contained a great deal of stand-up grappling, or wrestling. This realization has evolved over time as my understanding has grown, now aware that the Manchu were heavily vested in wrestling culture, ruling China for over 250 years during the Qing dynasty; the last of the dynastic eras of China. From there a growing realization of Han wrestling, jacket and no jacket wrestling from the Shaanxi, Shanxi provinces, along with a broader understanding of how much wrestling was part and parcel to so many cultures the world over, almost integral to our DNA as a species.

I could now see that a bulk of these ‘systems’ from northern China seemed to revolve ‘around’ grappling as a primary pillar, using methods and tools to facilitate ways to clinch and grapple an opponent, to throw or trip them to the ground.

The other primary art I trained and taught at the time of writing the above essay, was Taijiquan, specifically Yang family style which was originally known as small cotton boxing. The principles within that style also screamed grappling and I began to dig into the 13 keywords of Taijiquan, performing a comparative analysis of mantis boxing and supreme ultimate boxing after finding so many parallels. This is a working document that I return to from time to time over the years - Brothers in Arms: Mantis Boxing versus Supreme Ultimate Boxing

Arriving at ‘my’ 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing

Hook, Clinch, and Pluck were the first lessons from Wang Lang. These were followed by Lean. Lean was particularly elusive at first simply because myself being a striker/kicker I failed to see why we would want to lean in a fight, only to give our opponent a shorter distance to hit us in the head. Once applied to grappling and the close distance fight, leaning becomes integral to our survival.

The other keywords were increasingly harder to unravel, with growing absences between visits from my daemon. Long arduous periods of contemplation and frustration, times where I would continue to ask questions into an endless vacant void. From time to time though, my daemon would once more return, once more shredding the thick overgrown vegetation of confusion with razor sharp claws.

Once I could see through the adeptly graven undergrowth, and light shine upon the darkness once more, new techniques would reveal themselves. Eventually, a keyword, or two, would whisper from the lips of my daemon and wisp through the tattered leaves in the garden.

Adhere was the next to become apparent, especially due to its significance in BJJ, where controlling, or consuming space from an enemy while grappling on the ground was so significant. The same was true in stand-up grappling.

Strike was not as simple as it seemed. Ultimately, it is simple ‘to hit’, but why would something so obvious be a keyword? My daemon laughed at me, “If you don’t strike as you Enter, you’ll meet your doom.” he said. “If you do not strike to Connect, you will fail to find your enemies limbs, and meet their fists as you arrive.” “If you do not strike in the clinch, be prepared to receive…injury!”, he laughed harder.

Connect & Stick were the next keywords to be codified. Wang Lang, ever the sarcastic ethereal daemon, made disgusting references to gum, saliva, and the various stages of sticking, to bring these epiphanies to life. “That’s the easy part, but knowing when and how to use them without being punished is another issue entirely.” Offensive application versus defensive utilization was worthy of deep study, otherwise a broken nose would ensue.

Beng, to collapse and Fall Into Ruin came to me in the garden one day. Wang Lang was hanging out on the branches of my kale plants attempting to capture unsuspecting wasps, butterflies, and bees. As his hook snapped out to strike an unsuspecting passerby, he did not crush this victim with his deft strike, but caused it to collapse and fold in upon itself, crumbling to the ground below.

Beng was such a loud lesson that I had to write an article for it and publish it in a magazine for all to see. The idea that causing the opponent to collapse and fall into ruin using various methods, was revelatory to say the least. Especially since one of the core forms of mantis uses this in its name.

Wicked, or in other words, to be ‘sly, deceitful, or tricky’. Wang Lang just flat out hit me over the head with a heavenly strike on this one. What is a fake, or feint when boxing, if not a ruse to open up the opponent and land a strike? A loud noise, bang, or yell - are they not a diversion to enrapture our opponent for a brief moment so that we may gain unfettered access to enter and annihilate them? The use of pluck to force an opponent in the opposing direction of our throw, trip, or takedown, gain freedom to adhere and lean as we barrel forth into a takedown; is that not beguiling?

Wang Lang was rather condescending on that last one, especially since I had been using these tools for years yet failed to see the connection to the keyword he left etched in history.

Hang was another slap on the head, or ‘duh’ moment. Hang was pointed out by my daemon genius spirit. He vaingloriously proclaimed to me - “If you don’t root, lower, ‘hang’ on your adversary when engaged with hooks in the clinch, you’ll get tossed and trampled like you tried to wrestle an elephant!!!”

The Keys to the Style? Or Keys to the Stylist?

The 12 keyword formula of Tángláng Quán (Praying Mantis Boxing 螳螂拳) houses the principles that help define the art. These characters, or variations of them, have been passed down through the common vernacular of Chinese boxing methods in northern China. While not unique to mantis boxing, and evidence of their existence in other styles of the region and time period exist, they can establish a definitive strategy for mantis boxers; much more so than a collection of tao lu (forms) that have no consistency from one branch of the style to the next.

Replication of these keywords does exist among the various lineages of mantis boxing, especially in the first few keywords. No matter the style, many of the more obvious in name keywords such as: Strike, Crush, Hook, Enter, Lean, Clinch, Pluck can be witnessed in Mantis Boxing forms. Those which are harder to mimic in the air - Connect, Stick, Adhere, Hang, and Wicked, are absent in the forms from all indications, and are found rather through live training and sparring practice.

Many of the grappling specific keywords exist in various forms of martial arts still alive today. Although lost within Mantis Boxing lines, one needs simply look at other unarmed combative styles to find evidence of not only their existence, but also significance when it comes to fighting.

An art, of any type, is not defined by hard and fast rules, but is open to interpretation and adaptation by the artist. Keywords of a style, or system of boxing, are a series of principles to guide the practitioner. The definition of these principles and what they mean is highly variable and intimately related to the boxer using and/or coaching them.

The keywords can change from boxer to boxer, allowing for wide adaptation and freedom of expression, and each boxer can select which they rely on more than others. As long as the boxer adheres to a loose framework which includes the hook and pluck keywords, as well as the connecting and sticking specifically, then the stylist is still manifesting an art which mimics the fighting traits of the praying mantis.

These 12 keywords I pass on represent the foundational core of my mantis boxing art. Which strikes, kicks, throws, trips, submissions, you choose to use when you fight can vary widely from my own. And yet, with common principles we bond together as martial artists, share, and reward one another’s successes.

It took me six years to unlock what these keywords mean to me. Use them to discover your own methods. Keep what is valuable to you, discard what is not. Practice with it, fight with it, and your own truth will be one day be revealed to you. Validity in martial arts is not established by the opinion of others, but rather it is, and should be, measured by the success of the actions and execution of our methods.

To learn more about my 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing you can find a course I have available that combines video instruction with more detail in written explanations and descriptions of each of the 12 keywords.

LEAN (Kào 靠) - 12 of 12 - The Keywords of Mantis Boxing

Lean (Kào 靠) - to lean against one’s opponent. Due to the heavy reliance upon grappling and clinchwork in Mantis Boxing, Kào is an important keyword when engaged close range with the enemy.

Postural Defense

Once we are entangled…

Lean (Kào 靠) - to lean against one’s opponent. Due to the heavy reliance upon grappling and clinchwork in Mantis Boxing, Kào is an important keyword when engaged close range with the enemy.

Postural Defense

Once we are entangled in the Clinch (Lǒu 摟), we lean in to protect our position, or risk being taken down, or pushed over. We use our foe as a support structure, leaning against them whilst engaged in grappling and clinchwork. This is synchronous with Adhere (Tiē 貼).

While we Adhere, we shore up our position by using Kào. If this becomes impossible, we should break range and secure a better position. Kào can shut down my opponent’s attempt at hip toss throws; dropping my CG making it difficult for him/her to get their hips (fulcrum) under my CG.

It also reduces chances for them using Crashing Tide; their posture would become compromised simply upon attempt. Another advantage provided by Kào, is buffering the double leg takedown. If we’re upright, our legs are within easy grasp, and shortens the time until their shoot. By leaning, I can sprawl easier and faster by dropping my CG and putting my weight down upon their shoulders.

Overall, if we can stay inside the clinch with a solid posture, and forward lean, we can use this pressure to time takedowns with applied force.

Applied Force

In addition to securing our position with solid posture, we can also use the shoulder to assist in our own throws. The shoulder is used heavily in a lean forward type motion to affect applied force. This assists in the execution of many takedowns such as Crashing Tide, Single and Double Leg Takedowns, Point at Star, Reaping Leg, Crane Spreads Wings, and more.

CRUSH (Bēng 崩) - 9 of 12 - The Keywords of Mantis Boxing

Crush (Bēng 崩) - to ‘collapse and fall into ruin’. Also known as 'crushing' in many Chinese Martial Arts usages. Bēng is used to attack the vital targets in the midsection of an opponent. Effective strike targets such as: the liver, stomach; ribs, and the real treasure - the solar plexus, or central palace in Taijiquan. All of these targets can…

Crush (Bēng 崩)

Crush (Bēng 崩) - to ‘collapse and fall into ruin’. Also known as 'crushing' in many Chinese Martial Arts usages. Bēng is used to attack the vital targets in the midsection of an opponent. Effective strike targets such as: the liver, stomach; ribs, and the real treasure - the solar plexus, or central palace in Taijiquan. All of these targets can disable an opponent with one hit. This is seen in countless boxing matches, UFC battles, Muay Thai fights, and Kickboxing bouts. What happens when you land a good strike on an opponent in one of these locations? They "collapse and fall into ruin".

Bēng, as a principle, can use a fist, a knee, a kick, all to accomplish the goal of - causing the opponent to - 'collapse, and fall into ruin'.

Aligning the Strike

If you examine the height of many of the stances found in Chinese Martial Arts forms, and in this case Bēng Bù, you'll see that the strike does not align with the opponent's face but rather with the solar plexus/lower rib region of a ‘standing’ opponent.

Dropping the stance aligns the punch to the effective strike targets (liver, stomach, solar plexus). Mantis Boxing uses the Horse-Riding Step (Mǎ Bù 吗步), Bow Step (Gōng Bù 弓步) to accomplish this alignment of the attack.

Punching to the face is certainly an effective attack, but it also hurts the striker if they aren't wrapping their hands, or wearing gloves. Styles of Karate have Makiwara boards, and Chinese Martial Arts has Iron Palm/Iron Fist to train the hands so as not to break/injure the bones while connecting with someone's hard skull.

Iron Fist training takes months/years to train. Conditioning the bones and skin is only accomplished through extreme dedication and commitment. It is faster to teach someone a technique to strike the vitals, meanwhile working on conditioning the hands for longer term strategies.

Keeping in mind: the human skull has evolved over millions of years to protect the brain inside of it. It's hard, and not meant to crumble at the first hint of danger. Quoting a bike-helmet study published in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, "235 kg (520 pounds) or 2,300 newtons of force would be needed to crush a human skull, almost twice as much force as human hands could possibly muster."

Plainly speaking, anyone who has punched another human in the skull with a bare hand can tell you - it hurts when you hit. Knowing this, it is easy to see why a striking principle like Bēng, is so prevalent in the martial arts.

One might be better served destroying an enemy in a soft target, rather than risk the injury of straight on face punching. This can be seen in other Mantis Boxing techniques aimed at the head region using alternate hand shapes: White Snake Spits Tongue, Spear Hand, Thrust Palm, Ear Claw, Slant Chop.

--

Leave your comments and questions below. Don't forget to SUBSCRIBE and GET HOOKED!

The Way of the Mantis Boxer

Check out this preview of an awesome video put together by…

Check out this preview of an awesome video put together by two of my students - Vincent Tseng, and Thomas McNair. They worked hard on this live format depiction of the 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing.

Go to Vincent's channel to see the full video here - https://youtu.be/qPR83CZz8Bo.

More on the 12 Keywords of Mantis Boxing:

- Hook (Gōu 勾)

- Clinch (Lǒu 摟)

- Pluck (Cǎi 採)

- Connect (Zhān 粘)

- Cling (Nián 黏)

- Hang (Guà 掛)

- Wicked (Diāo 刁)

- Enter (Jìn 進)

- Crush (Bēng 崩)

- Strike (Dǎ 打)

- Adhere (Tiē 貼)

- Lean (Kào 靠)

Hooking Legs

The Leg Hook is a great easy to use takedown, but sometimes our opponent steps out on us on our first attempt. Here, Thomas helps demonstrate how we use a combination of Mantis principles (strike, hook, pluck, hang, lean) to execute our initial outside leg hook attempt, and then a follow-up inside leg hook if they step out.

Afterwards we tackle the ground component and what happens if they immediately try to pull guard.

The Leg Hook is a great easy to use takedown, but sometimes our opponent steps out on us on our first attempt. Here, Thomas helps demonstrate how we use a combination of Mantis principles (strike, hook, pluck, hang, lean) to execute our initial outside leg hook attempt, and then a follow-up inside leg hook if they step out.

Afterwards we tackle the ground component and what happens if they immediately try to pull guard.

Thanks for watching.

--

Like the video? Hit subscribe and Get Hooked!

Collapse and Fall Into Ruin - (Beng 崩)

A huge thanks to Gene Ching and the team at Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine for publishing my article this month. Such an awesome presentation! Thank you to my team - Holly Cyr, Vincent Tseng, Max Kotchouro, Bruce Sanders, and Sean Fraser for your assistance in making this happen. I am honored.

A huge thanks to Gene Ching and the team at Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine for publishing my article this month. Such an awesome presentation! Thank you to my team - Holly Cyr, Vincent Tseng, Max Kotchouro, Bruce Sanders, and Sean Fraser for your assistance in making this happen. I am honored.

The article is an expose on the Mantis Boxing principle of Beng (Crush, or to Collapse and Fall Into Ruin). You can read the rest of the article 'Collapse and Fall Into Ruin' in the July/Aug issue on store shelves now, or available online.

Research Notes: (Open) Praying Mantis Boxing vs. Supreme Ultimate Boxing

Sure enough, they were the same character. This lead to further research and comparisons, and soon I had a series of principles and sub-principles that drew a solid link between the two styles. The English translations people used can vary, but the character is found to be the same for each style. Below is a work in progress but it is far enough along that I can share it.

Current document status: open and active.

Edited - 3-2020

Brothers in Arms: A Comparitive Analysis of Praying Mantis Boxing vs Supreme ultimate boxing (Tai Chi)

Although tánglángquán (praying mantis boxing 螳螂拳) and tàijíquán, also known as tai chi (supreme ultimate boxing 太极拳) have very different purposes in today's world, they share a plethora of similarities beyond just common fighting arts from the late Qīng dynasty in China. So much so, that I believe that they are intertwined in history.

Shared techniques, principles, and geographic location all hint to a broader cross-pollination of Chinese boxing techniques in this time period, and region. The reality is these styles have more in common with one another than any defining uniqueness.

For the past few years I have been working intermittently on this project and from time to time come back and update these notes with more findings, and observations. I noticed similarities with praying mantis boxing and supreme ultimate boxing back in 2012 while researching texts. At the time, I was doing an article on one of the keywords of mantis boxing - Kao (Lean), and I recalled the 13 characters of tàijíquán had the same keyword.

I decided to do a character comparison between supreme ultimate boxing and mantis boxing, and see if it was the same 'kao'. Sure enough, they were the same character. I quickly then asked myself, ‘if these were the same, were their other keywords they had in common?’

This lead to further research and comparisons, and soon I had a series of principles and sub-principles that drew a solid link between the two styles. Showing clearly that they held more similarity with one another than not. The English translations people use can vary, but the Chinese character for many of the keywords is found to be the same for each style.

Below is a work in progress but it is far enough along that I can share it.

Note: when I refer to Taijiquan, I am referring to my background in Yang style Cotton Boxing. The name was changed in the late 19th or early 20th century when the practice shifted to fitness/health, from practical fighting art.

The original names of Chen, and Yang family styles (see below), were very different than the broad characterization of tàijíquán they are muddled in nowadays. From my research it has been hard to locate any evidence of the term tàijíquán in relation to these 2 families and their boxing systems prior to the second half of the 19th century when the Wu brothers wrote about it.

The Wu’s studied with Yang Lu Chan, patriarch of the Yang family. Who had trained with the Chen family but used his own combination of 37 techniques later known as Yang style tàijíquán but what Yang referred to as mianquan, or cotton boxing.

I’ve been able to trace (thanks to the translations of other researchers that speak Chinese) that the Wu’s later studied with Yang’s son after he passed away. Eventually they separated into their own style, and from all outward appearances, then began branding it as tàijíquán, or Supreme Ultimate Boxing.

One can quickly surmise that if the Wu’s called it such, that the grandson to the founder of the Yang family’s boxing system himself, Yang Cheng Fu, who incidentally is the most influential in the spread and recognition of tàijíquán in the world today, would lay claim to that name since the Wu’s learned their art from his family/grandfather.

From there the Chen family catching wind to this, could certainly take notice and say, ‘how can you be the ‘Supreme Ultimate’ Boxing if Yang Lu Chan learned from us?’ Thus, I believe the chain reaction that caused them to possibly take on the name/moniker of tàijíquán across all families.

Regardless of the chicken and the egg argument, the fact remains that the keywords used by tàijíquán share many common terms/principles with tánglángquán. Speaking to a larger overriding argument that there was more in common with all styles of Chinese boxing as a whole rather than differences.

The following are examples of the crossover between these two arts from northern China and the Yellow River region:

12 Keywords

of

Praying Mantis Boxing

(Táng láng quán 螳螂拳)

13 Keywords

of

Supreme Ultimate Boxing

(Tài jí quán 太极拳)

Arrow-Quiver (bīng 掤)

Stroke (Luō 擠)

Press/Squeeze - (Jǐ 擠)

Press/Push, Keep a hand on (àn 按)

Split (Liè 挒)

Elbow (Zhǒu 肘)

To Retreat (Tuì 退)

Left

Right

Central Equilibrium

Shared Keywords

Includes the primary keywords listed above, sub-principles listed in the tàijíquán manuals, and some tánglángquán correlating evidence.

Hook (Gōu 勾)

A predominant tool in tánglángquán and the first keyword, yet absent from the keywords in tàijíquán. However, it is still used in tàijíquán, and seen in techniques such as strum pipa, single whip, and snake creeps down. Hook, is also listed within sub-principles in tàijíquán manuals. Similar usage in application of ‘single whip’ vs ‘slant chop’, the initiation of pluck, requires a grab, or a hook. Hooking was not unique in Chinese boxing, and is quite prevalent in many of the various ‘styles’ from the region, including numerous shuai jiao applications. It would be more difficult to explain why ‘hooking’ wouldn’t exist, rather than why it does.

Pluck (Cǎi 採)

The ‘pluck’ principle is not only present in Chinese arts, but exists in styles from around the globe. In wrestling styles of the west it is commonly referred to as a ‘snap down’, but the arm variation of pluck, while included in the Chinese variant, exists in the west as a separate method known as a ‘drag’. This keyword runs strong in tánglángquán, and tàijíquán and it used heavily in conjunction with hooking, or splitting.

Enter (Jìn 進)

To enter as in a doorway. To advance. This keyword is shared between both tánglángquán, and tàijíquán, and other styles as well. The entire premise with xíngyìquán (mind intent boxing 形意拳) for example, is to go forth and blast someone with full intent. The concept of advancing in xíngyìquán is more in line with tánglángquán. Within tàijíquán, we see the concept of yielding and retreating displayed more prominently in their framework. I would attribute this less to any sort of superior approach, and more to do with the framers incorporation of taoist, or Chinese philosophical beliefs in general, into the tàijíquán agenda. The concept of Enter is straight forward - go in. Do not dally. Press the attack into the opponent to overwhelm them.

Lean (Kào 靠)

Both ‘styles’ work inside and outside of the clinch. Whenever we’re engaged in this range, we should be leaning forward to prevent easy takedowns, or being uprooted with minimal effort. The lean principle can be applied this way, but…it’s true measure is within the application of throwing techniques such as crashing tide, or white crane spreads wings. In both praying mantis boxing, and supreme ultimate boxing, the designer of the framework for these arts that later became known as the keywords, sought to convey significant value to this character and its importance.

Connect (Zhān 粘) | Cling (Nián 黏)

[In process] - Correlation between - Connect/Cling found in tánglángquán vs Stick/Adhere/Connect/Follow within tàijíquán. The significance of sticking.

Adhere (Tiē 貼)

Any grappling based art, or hand-to-hand combat system that includes grappling, whether on the ground, or stand-up, would be remiss not to include such a principle. This is further supported by this character being prominently listed in both tánglángquán and tàijíquán which use grappling and clinch work in their application. Tiē, is an emphasis on sticking, but closer in than the aforementioned sticking highlighted in both arts with Zhān, and Nián.

Elbow (Zhǒu 肘)

One of the core forms of mantis boxing is known as 8 Elbows, or Ba Zhou. The use of elbows is highly prevalent in Mantis Boxing. This correlates to the emphasis placed on the ‘elbow strike’ in tàijíquán in it’s prime principles.

Notes on ‘Ward Off’

The first keyword of taijiquan is often called - Peng (ward off). I was unable to prove this to be true in my research. Much of my findings indicated a schism in the tai chi community at large, over what the original Chinese character was. Some claim it to be peng, others bing, what I used above. What is the most important factor here is the Chinese character. If the community cannot agree on what the original character was then any translation or meaning of the first keyword is null and void. We cannot translate that which we do not know, or are incapable of agreeing upon. This coupled with Yang Lu Chan, founder of Yang family style taijiquan, being recorded as illiterate, makes it even more preposterous to claim original intent here.

Additional Commonalities

Kicking Methods

The two styles share their kicking strategy in common. Some of the kicks found in both styles are the ‘heel kick’, ‘toe kick’, and ‘cross kick’.

Striking & Blocking

The two styles share common striking attacks and counters.

‘Deflect, Parry, Punch’ from supreme ultimate boxing is also found in mantis boxing forms.

Both styles depend on an upper block combined with a counter strike down the middle; known as ‘bend bow shoot tiger in tàijíquán, or ‘pao quan’ in xíngyìquán. This move shows up repeatedly in tánglángquán forms such as Tou Tao (White Ape Steals Peach).

The use of the 'chopping fist' shows up in both styles. This appears to have been Yang Lu Chan’s primary offensive attack/bridge. I suspect, based on the expression and representation in the original Chen style form, known as ‘cannon fist’ that this is similar. This attack method is used repeatedly in styles of Chinese boxing found in the north and south, to include, but not limited to praying mantis boxing. Other styles/sets relying heavily on this include - gongliquan, lianbuquan, tongbei, changquan, choy li fut, etc.

The Beng Quan (Crushing Fist) is used predominantly in both mantis boxing and Yang’s mianquan (cotton boxing). This attack is commonly found in mantis boxing forms, such as Beng Bu, Lan Jie, Ba Zhou, and Tou Tao, and more.

White Snake Spits Tongue is also a shared attack in both systems. Parry and counter-strike to the eyes, or throat.

Throwing/Tripping Methods

The crossover here is expected to be heavy. I will name them as they come to mind, but given the prevalence of the Mongol influence in the north, and the wrestling techniques of the Steppe peoples permeating the local cultures, it is likely this will be one of the strongest areas of similarity and crossover. Many of the movements are even evidenced back to the 1500’s in Qi Jiguang’s unarmed boxing set used to train troops in the Ming dynasty.

Techniques

Snake Creeps Down is the same move/attack as found in tánglángquán’s piercing hook method.

Single whip in tàijíquán is the same method known as slant chop in tánglángquán.

Grasp Sparrow Tail:

Stage 1 - rowing hook variant (see below).

Stage 2 - known as double sealing hands in mantis boxing.

Stage 3 - known as ‘crashing tide’ in mantis boxing.

Stage 4 - double push takedown found in an opening move of mantis boxing form known as lanjie, which evidence points to meihuaquan origin.Step Up to Seven Star is a second variation of ‘crashing tide’ that is found in another mantis boxing form. The same move, expressed with variation on the leg execution based on grappling pressure of opponent. The monkey stance or bow stance version is heavy forward momentum when going from striking to takedown. The seven star variant is when adhering to the opponent in the grapple and using forward pressure (lean) and trapping the leg to prevent the step out.

Strum Pipa is known as ‘white ape invites guest’ in mantis boxing.

Diagonal Flying is a shuai jiao move known as a rowing hook. The flying diagonal is one variant.

Golden rooster rises up is also a rowing hook variant and is found in lan jie form in mantis boxing.

to be continued…

Two Roads Same Path

The two styles took very different paths as time passed, yet originated with a similar intent. Yang tàijíquán was very condensed; using one form to house the entire system of 37 applications.

Tánglángquán, on the other hand, had 2 or 3 original forms (allegedly), and later became bloated as more and more forms were piled on. The system split into multiple lines as did tàijíquán, except each branch with a multitude of varying forms, rather than a single representation, further diluting the art.

Tàijíquán, was also transformed into the health practice commonly known as Tai Chi today and was used for physical education. This took place in the early 1900’s; spearheaded by Yang Cheng Fu. It was excellent for all ages, and those who could not perform high impact exercise thus keeping it fairly intact through the ages.

Tàijíquán had already been split into different family lines (Chen, Yang, Wu, Wu Hao, and finally Sun). It split again post-transformation from fighting to fitness. The original Chen family style (Cannon Boxing), and Yang family style (Cotton Boxing), were combative and extremely condensed. See my article on ‘The Dirty History of Tai Chi’ for more details, and a bibliography of sources.

Praying mantis boxing, was also absorbed into the national movement for better health and fitness. Jin Woo, Nanqing Guo Shu Institute are examples, but with a different methodology. They added pre-requisite forms known as fundamentals training prior to being able to focus one’s studies on mantis boxing, or another style. In Jin Woo, practitioners performed sets at a faster, and more athletic pace, to a fault; as this later became a standard by which your ‘art’ was judged, versus the original combative intent.

In the end, it saved neither from becoming obsolete, broken, and losing their teeth. Lucky for us, the forms, and the keywords/principles survived; making reassembling the arts still possible.

Below are maps to show the provinces in China where these styles originate. Eastern Henan Province, Shandong, and Hebei province.

As Douglas Wile points out in his book - ‘Lost Tai-Chi Classics of the Late Ch'ing Dynasty’,

“the Yellow River basin was a hotbed for martial arts training and fighting. Many famous boxers emerged from this region and went on to be accredited with founding of their own fighting systems.”

Crossover of techniques and principles that work, or the use of a technique that defeated another opponent, would surely be picked up and used among anyone in the know.

The common use of bēng quán (crushing fist 崩拳), pào quán (cannon punch 炮拳), and pī quán (chopping fist 劈拳) in Xing Yi Quan, Tang Lang Quan, and multiple family styles of Tai Ji Quan offers a clear example of this cross-pollination of techniques.

Maps

Yantai, Shandong, China. Birthplace of Tánglángquán

Chen family village. Henan, China. Birthplace of Tàijíquán

Dai family biaoju company. Xingyiquan Region

Research Bibliography and Character Sources:

Lost Tai-Chi Classics of the Late Ch'ing Dynasty, Douglas Wile, 1996, SUNY Press

Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan - Fu Zhongwen, translated by Louis Swaim 1999, North Atlantic Books

The Essence and Applications of Taijiquan, Yang Chengfu, translated by Louis Swaim, 2005, North Atlantic Books

Brennan, Paul. 2013. EXPLAINING TAIJI PRINCIPLES 楊班侯 attributed to Yang Banhou [circa 1875] - https://brennantranslation.wordpress.com/2013/09/14/explaining-taiji-principles-taiji-fa-shuo/